China's Xi Jinping kicks off his third leadership term with more power than ever, but a mountain of problems to tackle, from a dismal economy to his own Covid-19 policy that has backed the country into a corner, and deteriorating ties with the West.

At home, Xi, 69, must fill myriad jobs in the party and state bureaucracy after the change in leadership at the top of his ruling Communist Party, following its twice-a-decade congress that ended last week.

The economy, to be managed by a lame-duck premier until a parliament session in March, is beset by zero-Covid, a property crisis and falling market confidence after Xi unveiled on Sunday a new Politburo Standing Committee stacked with loyalists.

Investors will look for clues to how China will tackle economic policy in the run-up to, and during, the party's annual Central Economic Work Conference, usually held in December, which sets the economic agenda for the parliament session.

Initial post-congress judgment was harsh: global investors dumped Chinese assets on Monday and the yuan tumbled to its weakest in nearly 15 years on fears that ideology increasingly trumps growth under China's most powerful leader since Mao Zedong.

In particular, the hopes of investors and countless fed-up Chinese that the end of the congress would see authorities begin to dismantle the stringent zero-Covid measures were thwarted by Xi's reiteration of the policy.

"My guess is that we will now see the 'full Xi' approach to everything," said Scott Kennedy, a China expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

"That very well could mean continued muddled economic policies, since he is clearly balancing growth with equity, security, and climate goals, and greater tensions with the West along a number of fronts," he said.

"But it also sets up the possibility that as China runs into more problems, Xi will be in a position to dramatically shift direction without fear of being undermined by other factions."

‘Winning formula’

With Xi increasingly focused on security and self-sufficiency, many China-watchers expect more of the aggressive diplomacy that has alienated Beijing from the West on issues ranging from human rights and pressure on Taiwan to support for Russia's Vladimir Putin.

Although viewed as abrasive in the West, that aggressive approach is popular domestically.

"I don't see China carrying out diplomacy any other way. It thinks it has found a winning formula, why change?" said a Western diplomat in Beijing.

China's strategy aims to win over "swing" countries to score United Nations votes, the diplomat said on Tuesday.

"We thought our friendship with China mattered, but now we realise it has given up trying to make friends with the West."

Washington said it had taken note of the congress and stressed the importance of keeping open lines of communication.

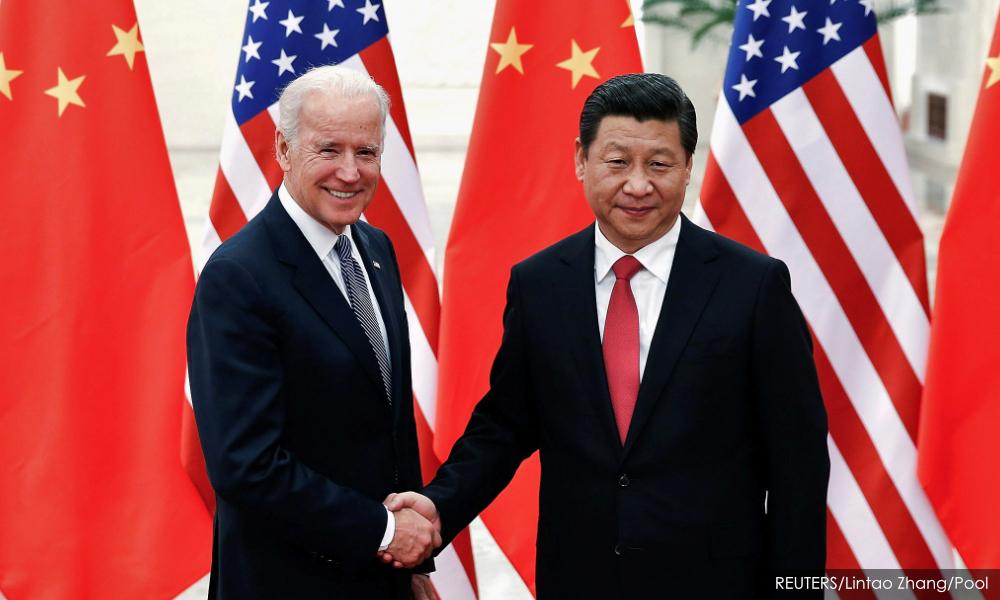

Xi and US President Joe Biden are likely to be in the Indonesian resort island of Bali next month for a meeting of the G-20 grouping, but it is not clear whether they will meet in person for the first time as heads of government.

Beijing has yet to say if Xi will attend.

Meanwhile, a sweeping US ban on exports of semiconductor technology to China further fuels Beijing's belief that Washington wants to contain it.

With Xi warning of a more dangerous world, party watchers expect Chen Wenqing, his minister for state security, to be elevated to China's top security role, a first such promotion that analysts say suggests greater focus on intelligence.

"Clearly we're not going to see an easing of, let's say, the competitive dynamics with the United States," said Dali Yang, a political science professor at the University of Chicago, who warned of "group-think" in a team of loyalists.

Xi’s men in

Having filled the top party ranks with his acolytes, Xi is set to replace leaders in key bureaucratic posts in the biggest reshuffle in five years.

Sources told Reuters that central bank chief Yi Gang is likely to retire next year, with Yin Yong, a deputy central bank governor from 2016 to 2018, seen as most likely to replace him.

Like many up-and-comers, he is a former subordinate from Xi's days as party chief of the eastern province of Zhejiang.

Other pro-reform policymakers excluded from the party's new central committee were outgoing economic czar Liu He, 70, and central bank party chief Guo Shuqing, 66. Another, Premier Li Keqiang, is set to be replaced by Xi's new No 2, Li Qiang.

Also among the newcomers is Ding Xuexiang, who was Xi's chief of staff and named to the new Standing Committee. He is widely expected by party watchers to be confirmed as ranking vice premier in March.

Unlike recent holders of that position, Ding does not have significant economic experience.

- Reuters