The recent furore over Sarawak-based Lina Samuel brought into focus that there are still thousands of Malaysians who have lived their whole lives in this country without formalising their citizenship.

Regardless of the exact circumstances of Lina’s case, which are still under dispute, this is very much an issue, particularly with small communities living in remote areas.

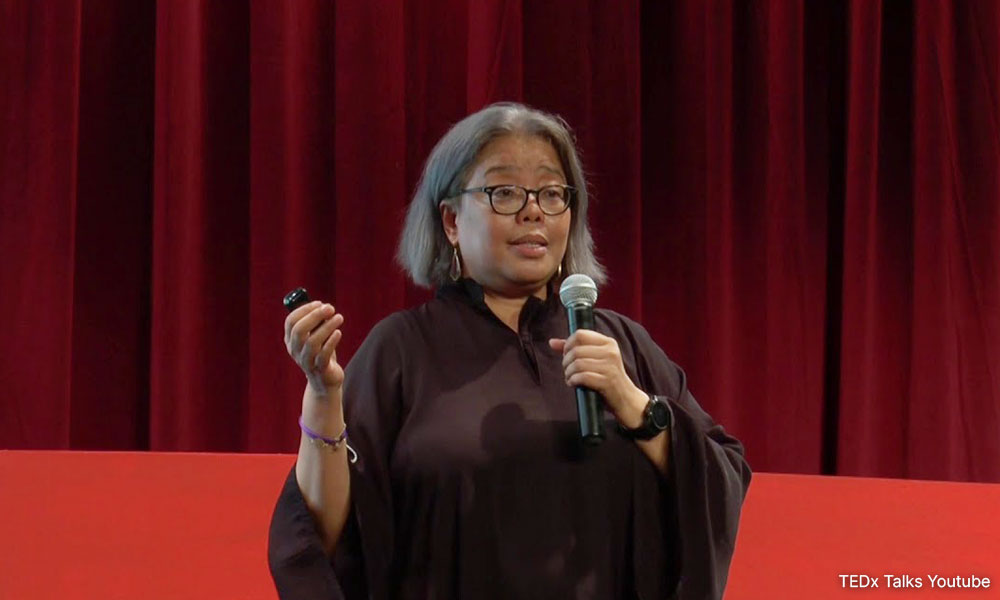

“In some areas, birth registration may not be widely available or accessible, making it difficult for individuals to obtain the documentation necessary to prove citizenship,” Yayasan Chow Kit (YCK) co-founder Hartini Zainudin told Malaysiakini.

According to her, statelessness in Malaysia is further complicated by the fact that some indigenous groups may have their own customs and rules that do not align with national laws.

For example, Hartini said for someone living in a small and isolated community on the border with Indonesia or Thailand, they could easily slip through the bureaucratic system if there is no impetus to facilitate their citizenship registration.

Nomadic groups or insular communities such as the Lun Bawang in Sarawak or the Bateq Orang Asli in the peninsula are among the most likely to fall into this category.

“There are government policies that restrict access to citizenship, such as laws that require proof of ancestry or residency that may be difficult to obtain.

“These policies can often disproportionately affect marginalised groups further - perpetuating the cycle of statelessness,” Hartini added.

Many still applying

On Thursday, Home Minister Saifuddin Nasution Ismail confirmed that among the many Malaysians applying for citizenship, there are about 3,000 applications from those born before independence.

“Many of them are already in their 70s and 80s,” he said.

According to Saifuddin, the number of overall pending citizenship applications is 133,436, while a total of 6,079 applications have been processed so far this year.

He added that his ministry is planning to approve at least 10,000 applications this year.

Responding to the minister’s statement, Lawyers for Liberty director Zaid Malek said that such situations often fall under Part 1 of the Federal Constitution (Second Schedule).

Part 1 stipulates that persons born after Malaysia Day (Sept 16, 1963) are citizens by operation of law. This rule also extends to anyone born within the Federation after Merdeka Day and before October 1962.

Denied access to healthcare, education

While these overall figures include a range of applicants, statelessness particularly affects those from B40 households, especially those who had limited access to education.

Concurring, Hartini said stateless children may face discrimination when seeking access to education.

“Without citizenship papers, stateless children may be refused admission to school, as well as being excluded from opportunities to take national exams or access scholarship,” added Hartini.

She also said that these individuals often face issues with land ownership because they lack proper documentation to prove their long-standing residency and ancestral ties to the land.

This means that they are at risk of eviction and displacement, even if they have lived on the same land for generations.

This also applied to children born overseas to Malaysian mothers and foreign fathers. However, in February, the government agreed to amend the Federal Constitution to allow mothers to get their parental rights.

Complicated process getting citizenship

According to the Peninsular Malaysia Orang Asli Villages Network chairperson Tijah Yok Chopil, the process for Orang Asli in the peninsula to get their citizenship is too complex.

“There was a case in Johor where a father did not want to fulfil the procedure of getting MyKad for his son and when the son was already an adult, he tried to go to the NRD (National Registration Department) to get his MyKad.

“By then, his father had already passed away. The NRD still wanted to get the father’s photo despite the fact that he has a mother, siblings and relatives,” said Tijah.

Tijah added that rural dwellers also face difficulties to visit an NRD office due to a lack of transportation.

As such, she suggested that the government and NRD conduct mobile operations in remote areas to help stateless individuals get their citizenships annually.

Suhakam commissioner Noor Aziah Mohd Awal told Malaysiakini that without proper documentation and legal status, stateless individuals may face difficulties accessing necessities.

These include education, healthcare, land ownership and job opportunity. The individuals may also be at risk of exploitation and abuse.

“A stateless person has no rights like other citizens. They are considered non-citizens who have to pay for education and medical treatment and cannot own any property.

“And they cannot open a bank account and if they work, they may be exploited by irresponsible people,” Aziah said.

Therefore, Aziah urged the government to implement proper policies to address statelessness.

She said that a registration system for undocumented and stateless individuals can grant them access to formal education and stable employment.

“They should eventually be granted citizenship, especially if they have never even left the country,” she stressed.