LETTER | Chicken shortage! Beef shortage! Soaring vegetable and local fruit prices! These are the endless news we face now and then and ever since the Covid-19 pandemic, the situation has only gotten even worse.

Food shortage and ever-increasing prices are always swept under the carpet with excuses from politicians such as food chain disruptions, global supply trends, supply-demand forces, increasing cost of importing fertilisers and grain supplies, lack of migrant labour supply, etc. are the usual humdrum of justifications that only leave 32 million citizens and millions of migrant workers in the lurch.

Mind you if we cannot even resolve our own food supply and security needs in peacetime, wonder what would be the consequences in an escalating period of global geopolitical strife or worst the eventuality of a war.

Malaysians may be too ensnared in the race politics and religious divisiveness that is peddled to the hilt as a power struggle since the mayhem of the Sheraton Move. It accelerates so fast that we remain blind to the pressing food security needs in the country.

While MITI in its Jan 30, 2021 media statement proudly announces a “sustained (trade) surplus trend for 23 consecutive years since 1998” the puzzle is why the working-class citizens end up paying increasing prices for food supplies and facing perennial shortages?

Despite Malaysia being “the world’s second-largest palm oil producer and exporter after Indonesia (and our) palm oil production (accounting) for 26 percent of world production and 34 percent of world exports in 2020” as is reported by the official website of the International Trade Administration, citizens are suffering from the ever-increasing cost of putting food on the table.

Imported food items

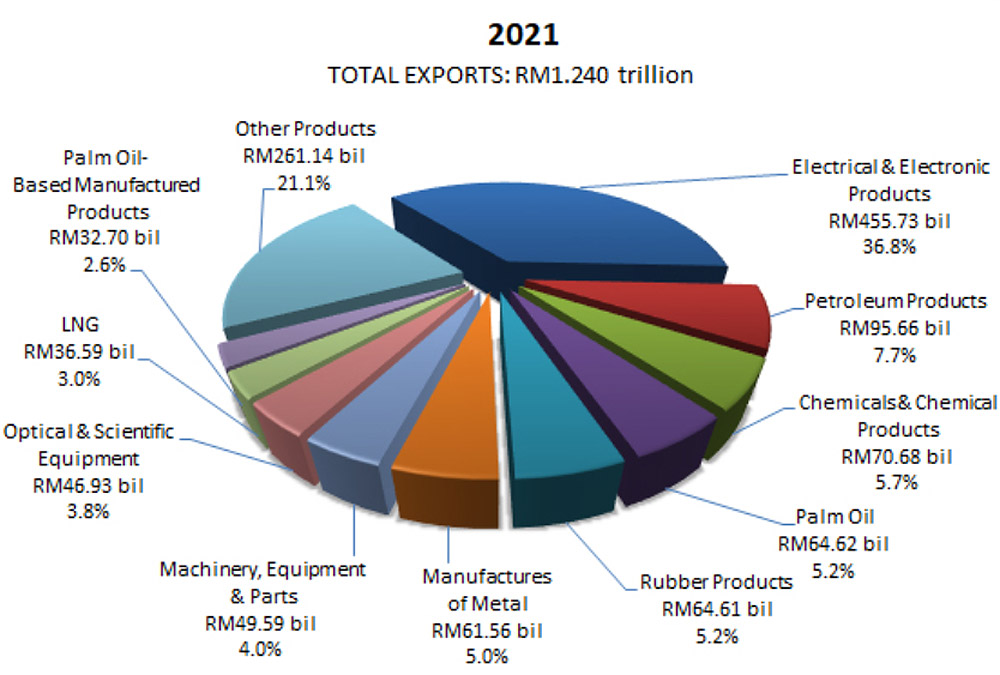

Despite a national earning of RM1.240 trillion in 2021 from our total exports as is reported by the official portal of Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation (Matrade), Malaysians are unable to see meaningful subsidization for imported food items.

And let us not forget that the of the various exports going out of Malaysia, palm oil only earned us 5.2% of the reported RM1.240 trillion in 2021. More than 80% of earnings came from non-agro based / food products.

The Agriculture and Food Industries Minister Ronald Kiandee in his winding-up debate on the Supply Bill 2022 in the Dewan Rakyat, assured Malaysians that his Ministry has “devised strategies to ensure stable food supply, reduce dependency on imports”.

But the minister did not explain why Malaysia’s agriculture sector, which was “one of the economic pillars to the country’s economy in its early stage of development with a share of 28.8 percent in 1970” had over the decades and by 2020 fallen to “7.4 percent to overall Gross Domestic Sector (GDP)”.

In recent years, the share of Malaysia’s Agriculture sector to the economy is comparatively small compared to our neighbouring countries such as Indonesia (13.7 percent) and Thailand (8.6 percent).

Agriculture sector

The official portal of the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) may seem most reassuring on its presentation of facts in its report dated Aug 26, 2021, about the state of and plans for our crops, livestock and fisheries industries.

But when we witness increasing amounts of citizens in the B40 and M40 groups are splitting hairs to pay for their daily sustenance, we have to ask honest, painful and really hard questions.

If the health pandemic of 2019 is explained as the root cause for our slide in the Self-Sufficiency Ratio (SSR), are we to believe that before the Covid-19 we were smooth sailing with our food prices and supply and demand matrixes?

If the struggling performance of our agriculture sector as explained by DOSM is owing to “higher cost in raw materials especially for the commodities related to food products” and that “for the last ten years, the index of foodstuff and feedstocks increased 24.4 percent” with “most feeding stuff for animals was imported mainly from Argentina, while for fertilisers, were from Canada and China”, then what happened to all our pre and immediate post-Merdeka capabilities and reliance in local farming, fisheries and livestock breeding that thrived without manufactured imports of fertilisers and feeds?

Let us not forget that we came out of WWII eating pucuk ubi rebus and ikan sepat bakar while rice was a luxury many could not afford. And where are we today?

Shortage of fries

A recent shortage of French fries owing to a fast-food chain facing a serious disruption in its potatoes supplies sent tongues wagging among the youth across the country.

Wonder what we will do when the average citizens can only have chicken, meat, fish, fresh vegetables and fruits sparingly?

Is our penchant for quick profits and fat earnings from taxation to be blamed for the neglect in the local food security production all these past four decades?

While the privatisation agenda of Mahathir Mohamad drove the private sector at a maddening pace that created pockets of billionaires and an unknown number of millionaires, the vast majority of the population have been drowning in a systemic and interlocked snare of the middleman.

While we had the noble idea in the 1970’s to implement agricultural science as a subject in schools and even set up a college to produce graduates in agricultural science in anticipation of the need to be self-sufficient in food and livestock production, we have instead surrendered all to the oligarchs operating mega palm oil plantations taking over from the lumbering barons who depleted our lands.

Food sector

The government’s reassurance that “efforts to rejuvenate the food-based agriculture sector through technological adoption will be able to boost agricultural production as well as addressing the unemployment issues” rings hollow. The question is why did we not address this problem in past decades?

As the number of unemployed persons at the national level has surpassed the pre-pandemic threshold and remain high at 768, 700 as of June 2021 (DOSM), we have to hold our policymakers and political leaders accountable in the face of rising unemployment, mismatched skills, export orientation at the expense of home-grown food securities, and increasing demand for cheap foreign labour.

Indeed any explanation and promises will not erase the looming food security crisis that Malaysians face. We have talked about it. Responsible media editorials have addressed the issues repeatedly. Netizens have written in expressing their concerns.

But as the days roll by, Malaysians are finding it increasingly impossible to put good, fresh, nutritious and balanced meals on the table daily.

Farmers and breeders are increasingly finding the ever-changing policies in place of no help to continue remaining as farmers and breeders.

Affordable food

Ask any Malaysian if he or she finds food prices affordable. Ask any family if they can afford to eat choice farm produce and have meat, fish and chicken as frequently as they desired.

The potential of the food security crisis is in the answers one would obtain from citizens. Mind you we are not into a global war situation. We are not even into a direct confrontation between global powers. The health pandemic was already good enough to register the very vulnerable state of affairs in Malaysia in so far as food security, affordability and dependency go.

If we do not regard Malaysia’s looming food security crisis needs as in need of critical, national and public appraisal then we must be prepared to face the eventualities for our own neglect.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.