INTERVIEW | Syed Husin Ali is no ordinary politician. A former PKR deputy president and acclaimed academic, he is soft-spoken but steadfast. He was also a long-serving political prisoner, who was detained without trial from 1974 to 1980 and has been an important figure in Malaysian progressive politics for most of his life.

Syed Husin was born in Batu Pahat, Johor on Sept 23, 1936, to a family with royal lineage from the Indonesian Sultanate of Siak. He had three older half-siblings and three younger siblings, the youngest of whom - Syed Hamid Ali - was head of PKR’s Batu Pahat division.

He was formerly president of Parti Rakyat Malaysia (PRM) from 1990 to 2003 until it merged with Parti Keadilan Nasional to form Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR).

Syed Husin contested three Dewan Rakyat elections in the 1990s but lost each time before going on to serve in the Dewan Negara for two terms from 2009 to 2015.

The father of three has written and edited approximately 20 books including "The Malays: Their Problems and Future", "Poverty and Landlessness in Kelantan", "Two Faces: Detention Without Trial, Memoirs of a Political Struggle", "The Malay Rulers: Regression and Reform", "Ethnic Relations in Malaysia: Harmony and Conflict", and "A People's History of Malaysia".

As a scholar, he constantly stressed the need to revisit Malaysia's official history, which he believes to be too much about individuals and groups who were part of the elite strata of society.

He believes there is also an alternative history that needs to be explored which tells of the struggle of the common man.

Today, as he turns 85, Syed Husin takes Malaysiakini on a look back at some of the notable individuals who accompanied or influenced his life’s political journey which spans more than 60 years dating back to the Merdeka era.

The Merdeka-era leaders

Syed Husin began his schooling during the Japanese Occupation and was nine when World War II ended.

He did his primary and secondary studies in Batu Pahat before obtaining a place at University Malaya’s only campus, then located in Singapore.

Being 21 when Merdeka was declared, it was almost inevitable that he be drawn to politics. However, it was not the parties led by Malaya’s elites that interested him.

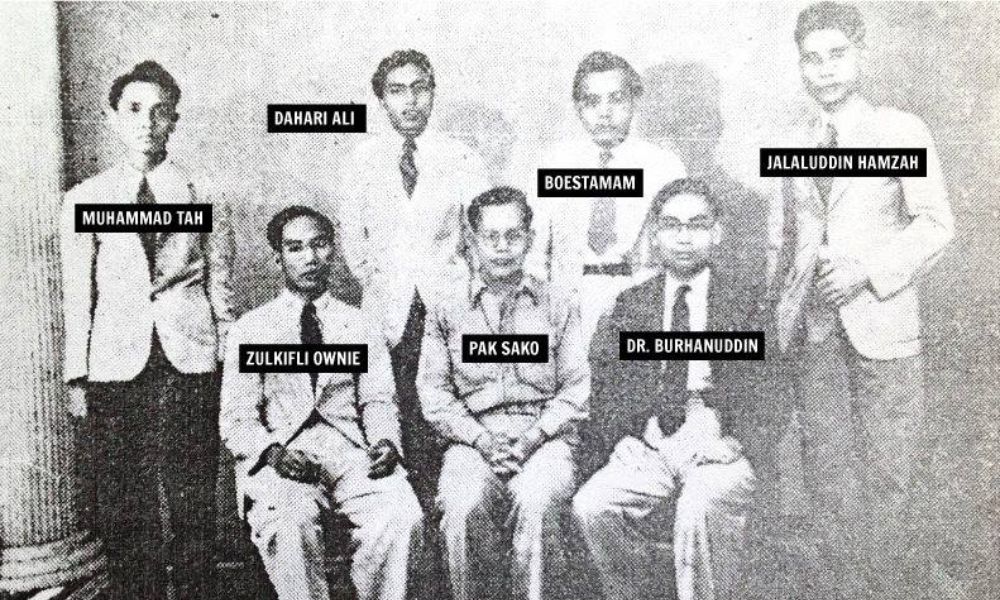

Syed Husin was drawn instead to grassroots left-wing leaders who championed the causes of Malaysia’s poor. Specifically, the trio of men who were leading the Labour Party of Malaya, PAS and PRM at the time – Ishak Haji Muhammad, Dr Burhanuddin Helmy and Ahmad Boestamam respectively.

“I met the three of them together in KL around the time of Merdeka. I was in my second year of university in Singapore and I went up to meet them in the PRM HQ, which was in Kampung Baru. At that time, all three parties were new and the Alliance of Umno, MCA, and MIC had swept the 1955 elections before Merdeka.

“Wahab Majid was also there, then secretary-general of PRM. He was the brother of Abdullah Majid who would become an Umno deputy minister and also an ISA detainee.

“The three of them were there and we sat conversing for about an hour. The gist of what they told was that ‘you are a student and you must remember that the fight for independence has not ended with Merdeka. We still have not gotten full independence, and we must continue fighting for that.’

“They also told me to always champion the welfare of the poor and the oppressed. This made a great impression on me,” said Syed Husin.

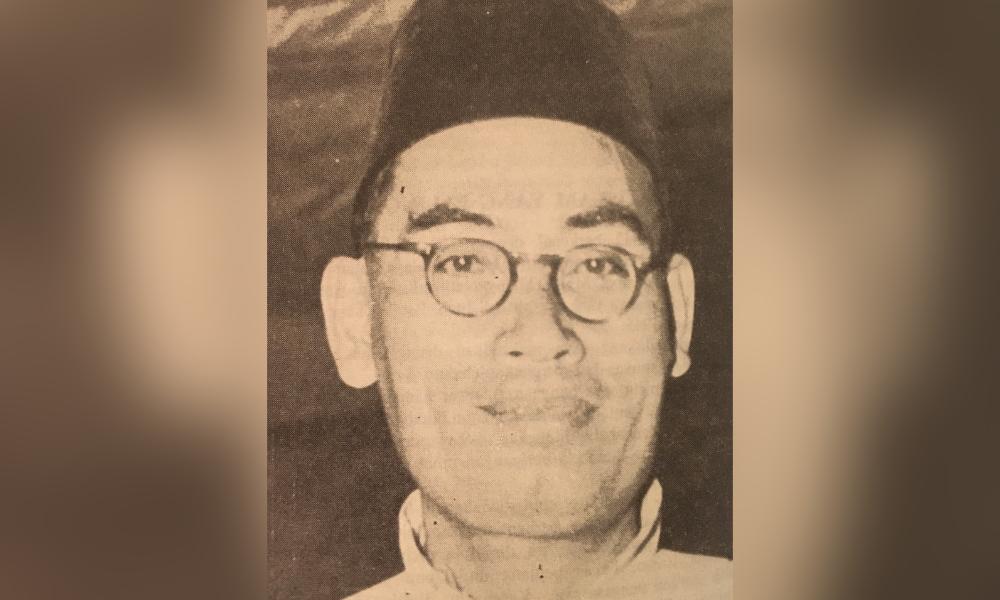

Dr Burhanuddin Helmy (1911-1969) was a religious person and a medical doctor whose specialisation was homeopathy, recalled Syed Husin.

“He was educated in India and he was a quiet, gentle man. Not a fiery speaker like Boestamam.

“He was an Islamist and a nationalist who preceded people like Tunku Abdul Rahman in the fight for independence. He was the second president of the Parti Kebangsaan Melayu Malaya (PKMM), an influential party that was formed in 1945 before Umno but which was suppressed by the British.

For a few years after the PKMM folded, Burhanuddin was not active party-wise, but he resurfaced as the president of PAS in 1956, a post he held until his passing in 1969. He was also elected Besut MP in 1959, serving a single five-year term.

“This was PAS in a very different era, with a blend of Islam, nationalism, and social justice. Burhanuddin was close to Pak Sako and Boestamam and the three of them agreed to take the leadership of these three different parties so that they could form a coalition to oppose the Alliance.

“But despite his leadership of the party, many in PAS were opposed to this proposal and it did not materialise.

“Later on in the 1960s, he was detained under ISA. He was not allowed to use the lavatory and had just a pot, and was unable to wash for prayers, and this (the detention) affected his health. He died young (at 58),” said Syed Husin.

Ishak Haji Muhammad (1909-1991) was the real name of the leader better known as Pak Sako.

“He was a strong nationalist and socialist. Like Boestamam, he was a journalist, and he was also known as a writer of satirical novels and short stories. Like Burhanuddin, he was in the PKMM earlier. But they made the decision that he would join the Labour Party,” recalled Syed Husin.

Even though that multiracial party had largely Chinese support and membership, he was readily accepted as party president and steered the party into a coalition with PRM as the Socialist Front, of which he was also chairperson.

The Socialist Front became the main opposition to Tunku’s Alliance coalition in the urban areas in the late 1950s, scoring some stunning victories in municipal council elections in Penang and Malacca.

“Pak Sako was a humourous person. He had an easy touch. Wherever he went, he would talk comfortably with strangers. He was not an officious type of person at all.

“Another thing was that he never drove a car. He would always walk or take the bus,” added Syed Husin.

Ahmad Boestamam (1920-1983) was a fiery speaker in public but he was a quiet man in person, said Syed Husin.

“He would answer questions, but he was not lively in person. He would come alive on stage as a public orator.”

Boestamam, who was elected as Setapak MP in 1959 representing PRM and the Socialist Front, had earlier risen to prominence as the leader of Angkatan Pemuda Insaf (API), which was the youth wing of the PKMM.

“Like the others, he too was detained in different spells (of repression). The first was under the British from 1948 to 1955. Then he came out (from detention) and formed PRM. But he suffered another round during the 1960s, during Konfontasi,” said Syed Husin.

He said Boestamam left PRM due to a misunderstanding with his successor Kassim Ahmad and went on to form Parti Marhein in 1968.

“Parti Marhein was not successful and he merged with Parti Keadilan Masyarakat Malaysia (Pekemas) in 1974, another left-wing party led by Dr Tan Chee Koon.

“But he was unhappy and he told me – I want to die as a PRM member. So he rejoined prior to his demise,” recalled Syed Husin, adding that Boestamam’s son Rustam Sani was also an important political thinker and writer.

Tajuddin Kahar (1923-2005) was born in Perak, Batu Gajah, and was a left-wing journalist in the early Utusan Melayu where he rose to be a news editor.

“He was also active in defending workers' rights and press freedom and was a presence when they went on strike, together with Said Zahari and Usman Awang to protest the takeover of Utusan by Umno.

“When they were all sacked from Utusan, he joined PRM and became secretary-general of both PRM and the Socialist Front.”

“He was more soft-spoken and he was not in the forefront, more the quiet organiser who spent a lot of time building the party. He was very disciplined, and sometimes others would get the impression that he was a bit aloof but he was not. He was very down-to-earth and friendly,” said Syed Husin.

Such individuals, said Syed Husin, were equally critical to the struggle of the masses but did not get the name recognition of other more celebrated figures.

DR Seenivasagan (1925-1969) was the leader of a very different People’s Progressive Party (PPP), which in the 1950s and 60s was very influential in Perak.

“The party was led by DR and his brother SP but even though they went on progressive lines, their politics were more pro-non-Malay. In fact, despite having Indian (or Ceylonese Tamil) leaders, their support base was very strong amongst the Chinese.”

Both brothers were long-time MPs in the Kinta Valley area and the PPP won control of the Ipoh municipal council in the early 1960s around the time the Labour Party/Socialist Front was heading the Georgetown administration under mayors DS Ramanathan and Ooi Thiam Siew.

“DR was a very well-known lawyer, taking many of famous cases, and also a very outspoken MP in the Dewan Rakyat,” said Syed Husin.

In 1965, DR famously made an allegation of corruption against then education minister Abdul Rahman Talib in Parliament, and repeated it in front of a huge crowd, including Rahman, at the Chinese Assembly Hall.

Rahman sued DR for defamation but lost the case and ended up resigning as a minister.

“However DR died very young (at 44), just before the 1969 elections where the PPP almost won Perak, and when his brother later took the party into BN, its supporters abandoned it for the DAP,” said Syed Husin.

Usman Awang (1929-2001) was born in Johor and educated only up to Standard 4 in a Malay school and yet he went on to be considered the best poet in the language – someone who wrote as a people’s poet, recalled Syed Husin.

“When he was 18, he was a special constable in the police force. And while in the police, he started writing poems and short stories. Then, he went over to Singapore and worked at Melayu Raya, which was a competitor to Utusan. Eventually, he was brought over as literary editor of Utusan by Samad Ismail.

“He used something like a dozen pen names. One reason was that if you were too critical of the government, they would 'take care' of you. But another reason was if there were not enough good pieces, he would write a few under different names to fill up the page!” Syed Husin quipped.

Together, the pair formed the National Writers' Association in the 1960s.

“He was president and I was secretary. Much later, in recognition of his contribution, he was awarded the Sasterawan Negara (National Laureate) in 1983, but the people already recognised him much earlier.

“He was very popular and his poetry was simple and dealt with people and poverty. He can weave words into striking phrases that are beautiful or nostalgic and even escapist.

“He was also always smiling, a very gentle person and a consummate entertainer, a joyful person. If I am around, I will be the target of his jokes!” said Syed Husin.

Syed Husin said when he was taken by the police in 1974, his wife Sabariah ran to Usman’s house next door, and they both went to see Labour Party leader MK Rajakumar.

“I stayed for a while in his house because when I graduated, I refused to work for the government, and stayed with him for a few months, and later when I got married, it was at his house.

“Earlier, Rajakumar was supposed to teach Usman English and vice-versa. But I noticed in the end, both spoilt their language and neither one learned the other language well!” laughed Syed Husin.

Hamid Tuah (1919-1997) was not a politician like the others but he was a peasant leader, recalled Syed Husin.

“During the Emergency, he was a police constable, but he was someone who cared for the people and carried out simple actions. He started at Sungai Sireh in Selangor in the early 1960s. There were many rural poor who needed land and they came to him.

“So he led them to open up the jungle, clear the land, set up houses, and also there was a river diversion effort to help farmers when their crops were facing destruction. But the government thought it was illegal and pulled down the houses and detained him.”

In 1961, when Hamid Tuah was arrested, hundreds of farmers protested outside the Pudu Jail, which alarmed the government, recalled Syed Husin.

“Later on in the late 1960s, he was involved in helping the rural poor in Teluk Gong and was detained again.

"Hamid Tuah was a very spirited person. He spoke very fast but was not an orator. He was very friendly and very helpful,” added Syed Husin.

“He was not involved in the Baling protests of 1974 but his children Siti Nor and Damhore were involved, albeit peripherally. Siti Nor went to become a long-time PRM activist.”

This article is part 1 of a three-part interview with Syed Husin Ali, an icon of Malaysian progressive politics for most of his life. He turns 85 on Sept 23.