It is the early afternoon at the floating village of Kampung Bangau-Bangau, a few students in uniform are walking home on foot. They pass several other children in shabby clothes playing by the roadside.

These children do not attend school and not by choice for they are all stateless.

According to the 2010 census, Sabah has the highest proportion of non-citizens in the country. One in four of Sabah's 3.9 million residents are non-citizens.

Kampung Bangau-Bangau is one of many floating villages in Sabah, mostly occupied by non-citizens. For tourists heading to famed islands around Semporna, the sprawling Kampung Bangau-Bangau is hard to miss - it is located next to the tourist jetty.

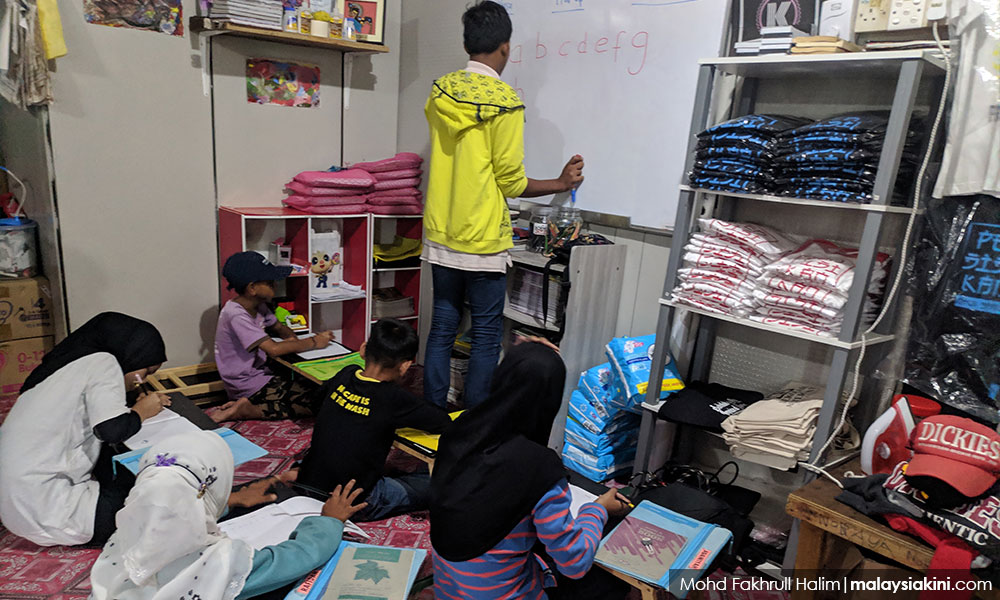

Some 40 stateless children from the village receive basic education at the Sekolah Alternatif Borneo Komrad at the adjacent Kampung Air.

School founder Mukmin Nantang, 26, runs the school together with Achmad Fatkur Raziq, 24.

Apart from writing and mathematics, the children learn basic skills such as commerce, agriculture, sewing and cooking, among others.

More importantly, the school teaches the children how to solve real-world problems they would eventually face as stateless people - exploitation at work, child marriages, sexual harassment and more.

The goal, said Mukmin, was to teach the children skills they could use to survive under their circumstances.

"When we ask them 'what is your ambition?'. They would reply 'doctor', 'lawyer' or 'soldier'. But if you ask them 'what will you do after you finish school', they would reply 'dish washer' or 'waiter'.

"A shame isn't it? They have ambitions... But they understand the reality they are in," said Mukmin, who started his teaching career with Teach for the Needs before starting the first Sekolah Altenatif in Tawau in 2016.

In Sekolah Alternatif, students are encouraged to chase their dreams. According to Mukmin, a doctor doesn't have to work in a hospital. His students can become a bidan kampung (village midwife).

A teacher, like him, need not be teaching in a public school. Sekolah Alternatif itself is a shack on stilts above seawater.

Siti Suhaimah Mustapa, 15, told Malaysiakini that she aspires to be a professional teacher. Coincidentally, she is a part-time teaching staff at Sekolah Alternatif, teaching younger children.

Suhaimah was one of Mukmin's earliest student recruit. In the early days of Sekolah Alternatif, Mukmin had to go house-to-house to convince parents and let him recruit their children.

Currently, Sekolah Alternatif is at saturation point. They have to choose who gets enrolled. Siblings of current students are given priority.

Achmad said Sekolah Alternatif has to expand and the plan was to establish more schools within the vicinity.

"Perhaps we are currently helping just 1 percent of those in need. Hopefully, one day, they will help others. At least they will be able to read, count and avoid being exploited.

"If you talk to the kids about their careers, they have all sorts of dreams, but they know where the limit is. What differentiates them from others is a piece of paper," he added.

Sabrin Mohd Amrin, 18, told Malaysiakini that he had to quit Sekolah Alternatif in 2017 to work a job that required 13-hour days and was paid RM350 a month. He was 15 at the time.

Mukmin eventually convinced Sabrin's mother that he could work at the school and attend classes at the same time.

Now, Sabrin attends class in the morning and sews bags that are to be sold in the afternoon.

"It's better now. I get to help my mother a little bit. I'm not sure how long I'll be doing this, I have to help my parents," he said.

Both Suhaimah and Sabrin are among hundreds of stateless children from Kampung Bangau-Bangau. Statelessness is a perennial problem in Sabah, due to poverty, ignorance and illegal migration.

Some children became stateless because their parents in the interiors did not register their birth in time. Others became stateless because at least one of their parents are foreigners.

Kampung Bangau-Bangau resident Siti Marina Salhati, 41, is a mother and Malaysian citizen, but her children are not and hence unable to go to school. Siti is one of several people Malaysiakini met who did not register their children's birth in time.

When speaking to Malaysiakini, she was full of regret that her children cannot attend school.

Achmad explained there were bureaucracy problems which made it harder for disadvantaged people to obtain identification cards for their children and this needs to be resolved.

Kampung Bangau-Bangau is located in Bugaya, which is a hotly contested seat in this election.

Read more: The who's who is the Sabah 2020 election

Incumbent Bugaya lawmaker Manis Buka Mohd Darah (Warisan) dan Mohd Daud Tampokong (Perikatan Nasional-Bersatu), when interviewed by Malaysiakini, acknowledged that statelessness was a problem in the constituency, but do not have specific policy positions to address it.

Daud, for instance, expressed confidence that Home Minister Hamzah Zainudin can resolve it. Hamzah is also the Bersatu secretary-general.

Senior fellow at Universiti Malaysia Sabah's humanities, arts and heritage faculty Wan Shawaluddin Wan Hassan said resolving issues concerning stateless children was complex due to the sensitivities involved.

Read more: Sabah Decides 2020: Making sense of the players, parties and battles

Shawaluddin, who had once promoted documenting all births even for non-citizens for record-keeping purposes, said the actual number of undocumented people in the state was uncertain and this made it difficult to formulate policies.

The fact that some of the new Covid-19 cases were brought to the country by people crossing borders illegally had added to the stigma.

"Stateless people are humans too. We need to find a resolution," he said.

Malaysiakini is currently providing stories on the Sabah polls for free. Continue to support Malaysiakini and independent journalism by subscribing for as little as RM20 per month.

Follow Malaysiakini's coverage of the Sabah state election here.