MALAYSIANKINI | For two to three weeks every month, Sanjitpaal Singh leaves the hustle and bustle of the Klang Valley to wander in our jungles.

As metaphysical as that may sound, his sojourns in our forests are not without a purpose - for Sanjitpaal is a rare breed who works with rare breeds.

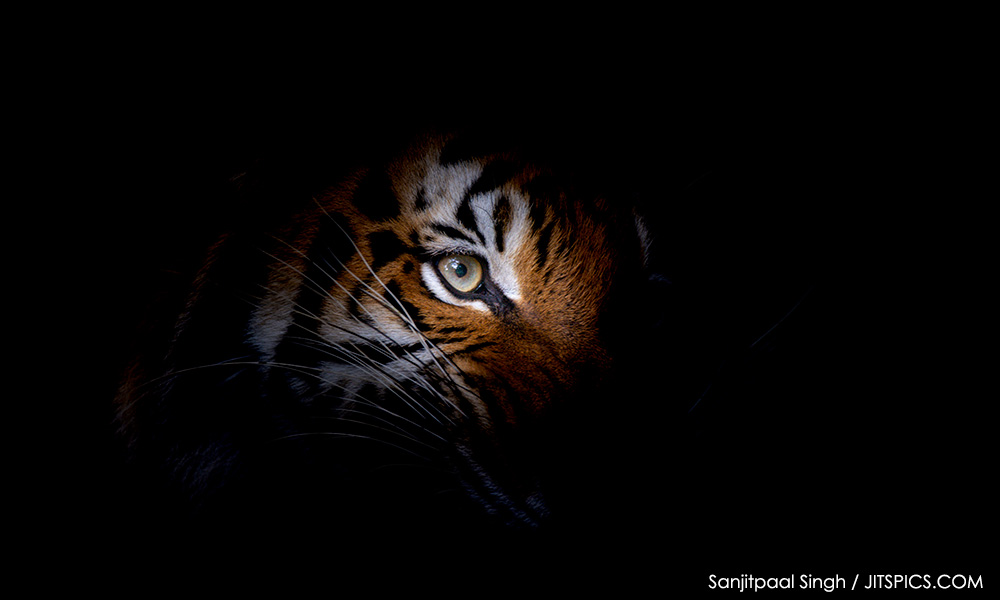

His speciality is wildlife photography, and he’s good at it. This is a man who will make his way through the virgin jungle and then wait for days outside a hornbill’s nest just for the chance to snap a photo of a youngling’s first flight.

Nor has his work gone unrewarded.

Sanjitpaal has been recognised many times with international awards and corporate sponsorships, but not for him the glare of the limelight.

His place is behind the camera documenting our natural wonders and making sure the rest of us realise how much beauty there is out there within our borders that is in desperate need of conservation.

Sanjitpaal, 37, has been in this line of work for 17 years and is long past the point where it became a calling.

“I have been honing in on nature, wildlife and conservation photography and focusing on animal behaviour in their natural habitat/environment," he tells Malaysiakini.

His work has a tangible practical purpose too, as he assists Malaysian field and scientific researchers on their expeditions for in-depth studies of their focused species.

WATCH: A day in the jungle with Sanjitpaal Singh

Meditative state in the jungle

Ever wonder what possesses a city slicker to walk away from suburban life to go and live in the jungle, sometimes for weeks in a row?

“I do what I do purely because of passion and for the love and thrill of adventure.

"Throughout the years, I realise that there is much to learn from being with nature and wildlife. The lessons to be brought home here is peace and serenity, tolerance and love.

"By studying and appreciating nature, we can encapsulate those traits to better ourselves as human beings towards others,” he says.

His goal is to inspire others through these pictures, and convey awe and wonderment through images, while focusing on details and expressions through photography.

“I hope the audience can feel from the standpoint and emotions of the subjects I photographed because these are living beings, and they deserve to be treated with love, respect and compassion, just as how you would treat those whom you admire most,” he says.

Despite the long hours and many days spent on a shoot, Sanjitpaal doesn’t view boredom, loneliness and losing one’s grip on sanity as issues he has to face.

“When I shoot, I tend to enter a meditative state and even forget that I’m alone in the forest. I feel more emotionally and spiritually fulfilled whenever I’m in nature compared with being back in the city.

"I admit that these are the best times of my life. Within nature, I feel free and unbound from superficial and worldly desires,” he says.

Sanjitpaal says he's very fortunate to have a supportive partner in his wife, Ravinder, who is a conservation biologist and thus, able to understand the demands of his work.

The ups and downs he faces on the job are also part of the experience.

“Although I do feel hopeless sometimes when the day doesn’t go my way. I guess that is just nature’s way of keeping me in a ‘balance’ - there’s a series of highs and lows and without these, there will be a standstill that heads nowhere.”

Famous conservationists like Dian Fossey (1932-1985) and “Crocodile Hunter” Steve Irwin (1962-2006) have met their deaths in the course of their work, and Sanjitpaal says that the work is not to be undertaken lightly without much preparation.

“Realistically, it is daunting as there is no part of nature we can predict. Nature and wildlife do not follow any rules. They make the rules.

"During expeditions, whether it’s a team of two people or 10, the dangers are real. The most important aspect of any expedition is that the team communicates well and keep others informed if there’s an imminent threat,” he says.

Sanjitpaal says that he’s been fortunate that he never had any direct encounters with poachers, although he has often come across them while studying footage from motion-sensor video cameras left in the jungle. He is also not weapon-trained. At least, not yet.

“Unfortunately, I have too much luggage to carry for almost any assignment in the forest. A good practice is to never go into the forest alone and always hire trained rangers or guides who have the necessary skills for a successful trip.

“Obtain your permits and ensure that the local authorities are well informed on your scheduled locations. Be safe and diligent at all times although you’re not weapon-trained. Although the tripod does make a handy weapon!” he says.

When left alone in the wild, which Sanjitpaal usually prefers while monitoring nesting behaviours, keeping still and silent is key to not only getting the shots, but to listen for any approaching threats.

“It doesn’t work out all the time as no matter how large elephants and tigers are, they are stealthy beings and will creep up on you without you ever knowing they were there in the first place,” he cautions.

“It is their space and we have to respect it with sincere intentions. Which, in my case, is to gather research data to help the forest regenerate for the future of all wildlife species within it,” he adds.

Sanjitpall's interaction with indigenous people is also key to his work. He believes that respecting the beliefs of the local indigenous people and honouring their culture is an essential part of his work.

“When embarking on a new project we need the support and cooperation of the people that live within or close to that area. Their support, survival skills and knowledge of the landscape are valuable for any successful project.”

“It always takes time for the trust to be built, and we eventually form somewhat of a brotherhood. They are the Swiss-army knives in the forests, and I feel that their lives should not be taken lightly as they live and depend on the land. They have families too, and the respect that they have for nature and wildlife is truly one to admire,” he says.

A working day

“This must be the toughest type of photography I’ve chosen to pursue,” relates Sanjitpaal.

“To start - travelling to locations within Malaysia can take an entire day. Depending on the wildlife species we’re focusing on, it is advisable to arrive at your shooting site as early as possible. This trip also likely includes additional travelling by boat, 4x4 vehicles and hiking.

“In my case, we start the journey into the forest at about 4am. Equipment preparations, checks and supplies for the following day are best done the night before. Practically, I sleep by 9pm (after dinner and backing up files from the day's work) and wake up at 3am,” he elaborates

Hiking, he says, could be anywhere between 30 minutes to seven hours - within moderate to extremely difficult terrain depending on the task of the day.

“The equipment is heavy and needs to be secured at all times. Now imagine doing that for 10-45 days in a row!”

Even the haze currently affected Borneo is another problem.

“The haze definitely dampens spirits. These disasters have a long term effect on insect and plant life. Insects will die, affecting the pollination of plants which we need desperately to cool the climate.

“The dangers are real wherever in the forest you are. And it’s a real physical job too. I have faced exhaustion, heat strokes, out of control boats that almost flung the team into crocodile-infested rivers.

“There are infections, strains on my back, arms and legs, extreme weather conditions, falling branches and trees, threats from animals, including cobras, elephants, orangutans, and the list goes on!” Sanjitpaal says.

Conservation is both urgent and essential

When asked about how much the environmental landscape has changed since he first got started, Sanjitpaal tries to be positive, but it is clear that he’s worried about the future of the world he immerses himself in.

“It seems more brown than green with much more depletion compared with when I first started, and it feels warmer in the forest. I suppose the effects of deforestation or land conversion are taking place.”

“I have also seen some wildlife species that have moved to higher ground where the forest is still lush and perhaps to avoid human interference.

“Spotting and getting close to wildlife has become more difficult, and they seem to behave more skittishly in the presence of humans. Which means it’s just harder to photograph their behaviour as they tend to flee,” he elaborates.

Sanjitpaal adds that jungle rivers are also less pristine, with the waters less clear, and many seem to be drying up.

It’s a shame as the key steps towards conservation are not too complicated. It’s about raising awareness and continued funding for conservation operations, enforcement and education programmes.

“Every person in the world of conservation is in need of funding to continue their mission. Funding is integral to every project and with the lack of funding, most people in this field feel demotivated because it is tough to move on and sustain their projects and the salaries of their staff.

“Enforcement activities also need to be fortified to curb further losses of our plant and wildlife species,” he says, adding that stricter legal policies and stiffer punishments need to be put in place.

To those who claim that there is no difference between the Barisan Nasional regime and the current Pakatan Harapan government, Sanjitpaal begs to differ.

“It’s most definitely improved under the new government. Malaysia has enforced new laws and has put more enforcement officers on the ground. This is a good start.

“Hopefully, Malaysia can deploy more enforcement officers in various forests in every part of the country to safeguard our animals from poachers. It may not be an easy task, but it is possible,” he says.

Photography is not a dying art

The evolution of technology has been a tremendous boon to wildlife photographers, but at the same time, this means that with great cameras in the hands of amateurs, there are people who undervalue this profession.

Sanjitpaal says that everyone has the ability to see things differently, and photography is about perception and perspective. He emphasises that he did not start with the best of equipment, and while he has invested heavily over the years, it is beyond his means to purchase cutting edge cameras.

He’s currently using Nikon camera gear that is cumulatively worth a cool RM100,000.

“Equipment make this line of work very expensive. We also need to consider laptops and computers, software, heaps of external hard drives for archiving and the list goes on,” he explains.

“It’s what you make of what you have in hand. Every photographer is different. Each with boundless limits of creations we can produce, and that’s the beauty about this work. In the beginning, one might spend tremendous amounts of time on visual research and understanding the rules of photography. When you keep at it, it becomes a natural extension of yourself.”

“Photography to me is an expression, and I encourage everyone with any type of camera to discover their potential. You will discover what you are most passionate about as a person.

“At the end of the day, all of us still need to survive and have bills to pay. Keep at it, work hard and if your client does not like your work, those are the clients you do not want to work with,” he added.

Sanjitpaal, who is of Malayalee/Punjabi descent, has received a fair amount of recognition of the years.

He was a semi-finalist for BBC-Shell Wildlife Photographer of the Year Award in 2006 and 2007 (UK) and received the ‘Malaysian One Earth Award’ in 2009 (Malaysia).

Sanjitpaal was also a semi-finalist for the Veolia Environment Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2011 (UK) and runner-up at the International Photography Awards, Professional Category (Nature/Trees), September 2012 (US).

Most recently in 2017, Sanjitpaal received the Conservation Leadership Award (UK) for continuing to support hornbill conservation in Malaysia.

He has also received numerous accreditations working together with environmental NGOs, advertising agencies, magazines and daily press. Sadly, despite his branding and copyrighting efforts, he frequently encounters people reprinting his photographs without permission.

“Unfortunately, it’s mainly by local and international media to sensationalise their stories. Most often these images are credited to the source which I initially contributed to.

“So, I’ll just drop them an email to introduce myself and inform them of the original artist. They mostly do comply, and it is very kind of them,” he says.

Sanjitpaal welcomes proposals for expeditions to assist in collecting visual documentation for conservation projects. He works on the basis that the photo rights are to be shared and free to use as long as the materials promote conservation and help NGOs receive future grants and funding from corporate funders.

He recently joined forces with a team of photographers to provide these services.

One direction in which he does not expect to go in is to be a celebrity wildlife television host like the afore-mentioned Crocodile Hunter!

“That would be awesome! However, I do not think that I can be the best fit for this type of TV show because I’m not formally trained in the fields of science and biology.

“If my part in a programme is to be a moderator to seek out wildlife species and photograph them by collaborating with field researchers and biologists, then I would surely consider it,” he says.

It all began with the zoo

Some people are under the misapprehension travel to exotic places around the world is needed to find interesting photography subjects.

Sanjitpaal, however, says that the Malaysian jungles have provided him with its limitless fascinating subject matter. As far as he is concerned, every place and subject is special and has its charm.

“For the past several years, I have mainly been photographing hornbills in Borneo together with a research team. Hornbills are very romantic birds, and it is astounding to document their behavioural patterns,” he says.

Sanjitpaal intends to expand and concentrate on critically endangered wildlife species. Interestingly, he is not one of those conservations who feels that zoos are outdated and should be banned.

“Zoos are very important to me. I grew up and eventually became a wildlife photographer due to numerous trips to zoos and bird parks as a kid. I can see animals up close, and I always admired these creatures and their features. I was always inquisitive on their lifestyle too.

“All animals are unique, and we can learn much from a day’s visit to the zoo.

“Zoos also act as a gene bank for endangered wildlife. Most international zoos are also supportive of conservation efforts by funding local projects as a global effort for wildlife conservation,” he says.

MALAYSIANS KINI is a series on Malaysians you should know.

PREVIOUSLY FEATURED

The video journalist helping Orang Asli save their lands

Heritage activist who promotes classic facets of Penang

Making games Malaysians can be proud of

'This is not poverty tourism': Helping KL's homeless find their strengths

The Malaysian giving cancer patients a lifeline