COMMENT | Malaysia is a nation with extensive coastlines, where fishing communities play an important role as stewards of the sea. In celebrating World Oceans Day today, it is timely to highlight the relationship between fishermen and the sea, focusing on a small area south of Penang island which will be affected by the proposed Penang South Reclamation (PSR) project. In order to understand the potential impacts of PSR on Penang Island South, we should first get to know the special qualities of this area.

Penang Island is shaped like a turtle, looking north. George Town is laid out on the only flat promontory (hence, the local name, Tanjung), while the other three “feet” of the turtle are hilly, rocky and forested. The northwest promontory, formerly known as the Pantai Acheh Forest Reserve, has been gazetted as a national park. The two hind feet of the turtle are Tanjung Chut in the east and Tanjung Gertak Sanggul in the west.

Like many locals growing up in Penang, I visited the kampung, seafood stalls and beaches of Teluk Kumbar and Gertak Sanggul. But focusing for most of my adult life on what is now a Unesco World Heritage area in George Town, I was scarcely aware of this unique area to the south.

The two feet of the Penang Island turtle straddle a sheltered, shallow seabed, flanked by Pulau Rimau and Pulau Kendi. This is the richest fishery in the northwest of Peninsular Malaysia. As noted in a recent Al Jazeera report, Penang island’s southern sea is known as the “Golden Place” or “Golden Zone” and ought to be recognised as a national treasure and indeed, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) academics have at various times suggested that Pulau Kendi should be nominated as a National Marine Park.

Most of the small-time fishermen here operate within five miles of the coastline, where the marine bounty is plentiful. I spoke to a fisherman at one of the jetties. “This is the main prawn area for the whole of Penang. If we want to catch prawns, we take our boats there out in the daytime. If we want to catch fish, we go further out at night. If we want to catch a crab, we set our nets in the mudflats and come back a few days later,” he related. Indeed, we could see the horizon crowded with several dozen boats. A friend showed me his photographs of the boats at night, a thick cluster of small lights.

Many conditions make the sea in Penang Island South an exceptional fishery zone. The curvaceous coastline hugging pristine beaches, small areas of mangrove and extensive tidal mudflats rich with nutrients. About 3km from the western headland is Pulau Kendi surrounded by hard and soft coral, while 380 metres from the other headland is Pulau Rimau where some fan coral survives.

Between 2008 and 2018, the Fisheries Department has dropped more than a hundred artificial reefs around Pulau Kendi to spur fish populations. The natural coral, the artificial reefs and several old shipwrecks, as well as the tidal mudflats, combine to make this “marine garden” an ideal fish spawning and breeding ground.

Fishing boats seasonally come to this “Golden Zone” from as far south as Pangkor Island, Perak, and as far north as Langkawi, Kuala Kedah and Kuala Perlis. Fishing trawlers and even Indonesian boats have been caught illegally encroaching in the waters of Pulau Kendi. The marine life spawned in this area makes their way to the waters of northern Perak, where they contribute to the fish landings of the Perak fishermen.

Penang Island’s southern sea is visited by the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin and the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise. Along the southern shoreline are five nesting sites for turtles, especially the green turtle with rare sightings of the small migratory Olive Ridley turtle listed by International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as “vulnerable”. From the last Olive Ridley nesting at Pasir Belanda, 70 baby turtles were released into the sea as recently as March this year. In view of their endangered status, the international nature conservation organisation, Rainforest Rescue, has released a petition to save Malaysia’s turtles.

The fishermen native to Penang Island South are traditional fishermen whose fathers and grandfathers were fishermen before them. Collectively, they have the know-how to deploy more than a dozen types of nets and a variety of traps, each net or trap customised for the desired catch. These fishermen could be called “artisanal fishermen” as they use traditional methods and fish in a more sustainable manner than commercial operators which tend to overfish. They are also called “inshore fishermen” as they use small boats and operate within eight nautical miles from the coastline.

In contrast to commercial operators who engage in deep-sea fishing over days or weeks and refrigerate their catch, the inshore fishermen typically stay out at sea for five to 10 hours at a time. The freshness and quality of their catch are unmatched by commercial vessels, and their return from sea is daily awaited by Penang’s local consumers, restaurateurs and food operators.

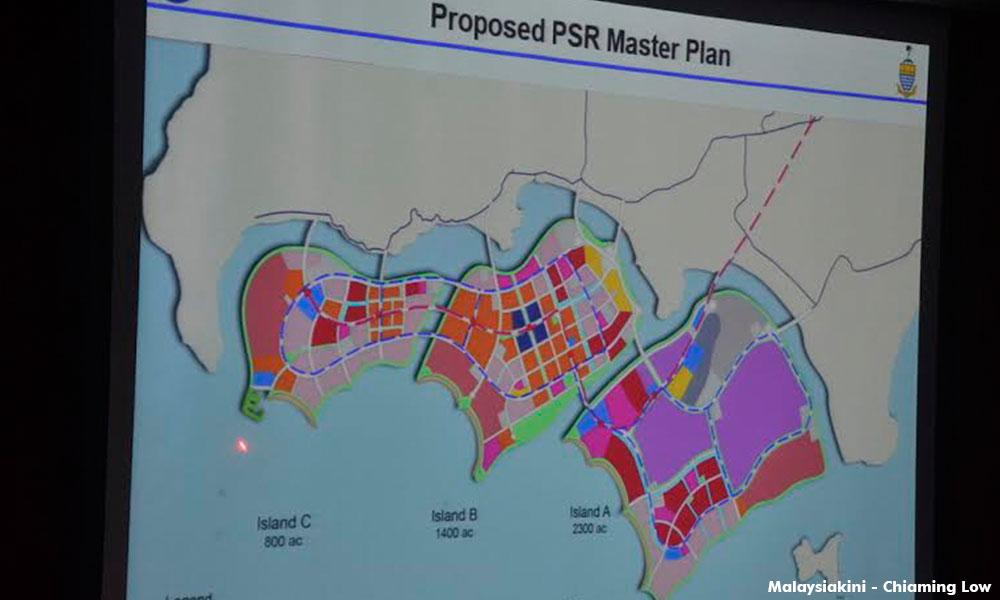

The Penang South Reclamation (PSR) proposal has drawn attention to the backwater of Penang Island’s southern coast. The EIA display period over the month of Ramadan has just concluded. The PSR proposes to reclaim three islands with a total of 4,500 acres filling in the area between the two feet of the turtle.

In the immediate “impact zone” of the proposed reclamation area are four fish landing points: Gertak Sanggul, Teluk Kumbar, Sungai Batu and Permatang Damar Laut. However, the larger “impact zone” also includes landing points in Pulau Betong (west coast) and Sri Jerjak, Batu Maung and Teluk Tempoyak facing the Penang channel. The LKIM Jetty at Batu Maung operated by the Fisheries Development Authority of Malaysia (LKIM) is a major fish landing station with cold storage facilities, frequented by commercial boats that operate in the vicinity of Penang Island South.

How many fishermen will be affected by the Penang South Reclamation project? The "18 Nasihat" released by the National Physical Planning Council (MPFN) in April this year mentioned 805 registered fishermen with families totalling 3,140 people but, in fact, these figures only correspond to the EIA “study area”. The EIA itself gives a Fishery Departments’ 2016 figure of 2,757 registered fishermen operating within the impact zone.

Of this number, the EIA says that up to 1,591 fishermen landing their fish at LKIM Jetty in Batu Maung should be discounted because they tend to operate larger boats, catching their fish further afield, leaving 1,116 registered fishermen. The fisherman’s association (PNPP) estimates that 1,800 fishermen will be affected. Many of Penang’s 4,817 registered fishermen (about 6,000 if unregistered fishermen are included) frequent this area at certain seasons. As mentioned earlier, the area even attracts fishing boats from other states.

According to a fisherman from Sungai Batu, the EIA report for the PSR underplayed one important factor - the southwest monsoon. When the second Penang bridge was being built, the seabed which was dug up for the piling was dumped beyond Pulau Kendi, he said, pointing to the island to the southwest. “There was a delayed effect but the southwest monsoon brought all the sludge back here. Our beaches were covered with sludge-mud and it took a few years for the fish and prawns to fully recover.”

Recent news reports about heavy metal pollution and rising toxicity levels in Penang’s seas, possibly linked to the northern reclamation works in Tanjung Tokong, suggest that our marine resources are already under stress. The Penang South Reclamation is likely to adversely affect the fisheries industry in the impact zone, where wholesale values of fish landings (RM42 million, not including the LKIM Jetty), the marine cage culture especially near Sri Jerjak and Batu Maung (RM60 million), hatcheries (RM8.8 million), brackish water pond culture (RM19.6 million) and oyster culture (RM409,000) all using on seawater, and recreational fishing (RM5.3 million), yielded a total annual economic value of about RM136 million.

In a recent newspaper interview, Professor Zulfigar Yasin from USM said that the Penang South Reclamation EIA should have covered an even larger area, as the sea cage fish farms in Batu Kawan, as well as clam aquaculture in Pulau Aman and north Perak, might also be affected. In 2017, Penang’s marine aquaculture industry accounted for 55 percent of Malaysia’s RM2.9 billion annual marine aquaculture harvest, which in turn constitutes a quarter of the fish harvest in Malaysia.

Zulfigar urged the government to think in a more holistic manner. “For example, if a certain pollutant from a reclamation must exceed 10 units to be considered illegal, but now three reclamations are producing nine units each, none would be deemed to break the law – even though they total 27 units. Who is to be held responsible when the fish is dead in this event?"

Much more can be said about the Penang South Reclamation, purportedly undertaken for Penang’s "smart and green" future. A well-known writer has already written about the potential effects of sand-mining in Perak. In view of the climate emergency and worldwide depletion of fish stock, one questions the Penang state government’s wisdom in undermining our local fisheries, food security and climate resilience.

SALMA KHOO NASUTION, a former Penang Island city councillor, is with Penang Forum, a coalition of local NGOs.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.