COMMENT | Before one is startled by the title, keep in mind two things: what Buddhists have long discovered has proven to be wise. Everyone goes through the process of birth, old age, sickness and death. More importantly, every country will experience the same.

China will not disappear from the face of this earth, barring a nuclear war. The same applies to Japan. But the problems and strategic implications to confront Japan are far deeper than what some Japanese may concede.

To begin with, Japan is fast ageing. But so are Asian countries like South Korea, Singapore, and soon enough, Malaysia. Any population that has a demography where 15 percent of the people are above the age of 60, according to the United Nations, would be defined as an ageing society. Malaysia's population will enter that stage in 2023, according to the research of Khazanah Research Institute. Japan has experienced this problem since 1992.

By denying they needed an inflow of fresh immigrants and labour workforce, Tokyo has worked itself into a corner. Japan has to import close to a million workers from some 12 countries by 2030. This is a tall order by any measure. But this is what Japan ultimately has to do.

China is ageing too, due to its previous one-child policy. But the speed at which Japan is ageing, where it's population will dip to 80 million people by 2050, is something which has never been witnessed by any modern society before.

Malaysia, if it is to avoid the dire effects of ageing from 2023 onwards, cannot be importing foreign workers non-stop, for this would keep the wages of the Malaysian workers perennially low, leading to a race to the bottom. Thus Malaysia must learn from Japan, indeed, and from countries like South Korea, even Singapore, on how they deal with ageing; with Japan as a prime example.

Secondly, when a country begins to age, it will be more pacific and peaceful in nature. Japan, by this token, will rely on the military preponderance of the United States to counterbalance China in the region - even as an ageing China tries to modernise it's military force as quickly as possible to prevent the need to rely on its veterans, old warriors, indeed, a civilian population with which it does not need to call upon, since all would be ageing, anyway.

Japan, willy-nilly, has also begun switching to robotics and automation to make up for the shortfall in human labour. If Malaysia does not have a strong tradition of innovation and science - with an excessive focus on religious education - Malaysia cannot be a high-income nation by 2025 either.

Thirdly, Japan has a cabinet that is functional on the surface, but dysfunctional in reality. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has liberalised the Japanese economy in various sectors to enable a large influx of blue-collar workers to fill up the acute labour shortage.

Yet some of his ministers have been slow moving in explaining the location, time and syllabus of the Japanese language exams across the respective sectors. Granted the internal dynamics in a Japanese coalition government, what has happened in Japan can come back to haunt Malaysia too, which is also operating as a coalition government.

For now, Look East does not mean learning from Japan, and being over-awed by it, but understanding the whims and idiosyncrasies of the whole structural edifice of Japan, and subsequently, all ageing societies.

Setting the correct course for Malaysia

When one looks to China, one is easily enamoured with its grand ambition to supplant and replace the United States in some 10 strategic sectors of the global economy driven by algorithm, automation, artificial intelligence and big data analytics. Yet, China is facing the same kind of problems of Japan; though Japan is facing them first.

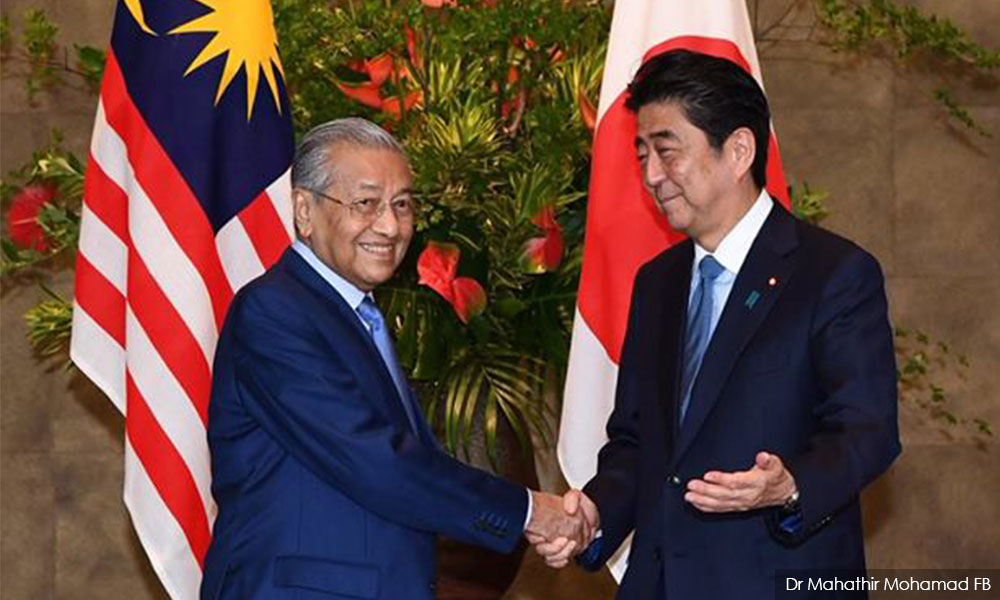

The key to setting the correct course for Malaysia, à la Look East, starts from learning from the pluses and minuses of Japan without fail. Ideally as soon as possible. After all, Malaysia under Dr Mahathir Mohamad in 1981-2003 was administered not unlike the model of the Japan Incorporation.

With the transition in its horizon, second-term Prime Minister Mahathir has to explain to his cabinet colleagues that Japan has internalised both the strengths and weaknesses of the West, and has sought to solve the problems with Japanese ingenuity, tradition and pride.

Malaysia, as an emulator of Japan at one stage, and a former colony of Britain, also suffers from the combo of the problems and predicaments. This is why all the ministers have to take Japan seriously. Not merely for the opportunities it offers, but the strategic problems which will confront Malaysia, Japan and Asia, if not the world.

RAIS HUSSIN is a supreme council member of Bersatu. He also heads its policy and strategy bureau.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.