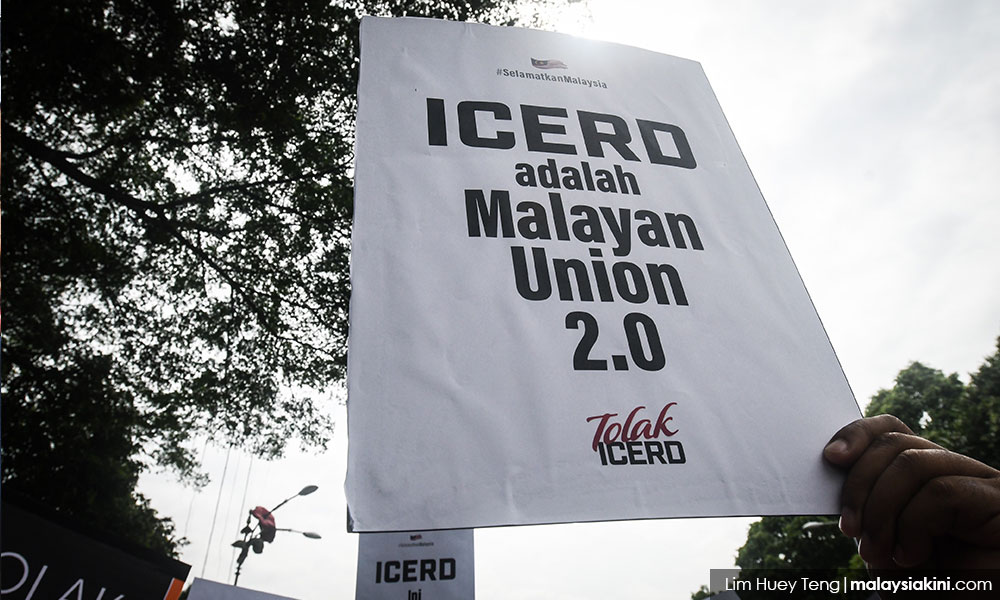

COMMENT | One year after the new Pakatan Harapan government came into office, we find that human rights in Malaysia continue to be perverted because of apparent lack of political will to significantly reform the old Malaysian institutionalised politics of racism and racial discrimination. It is disappointing to say the least, that Harapan reneged on their promises to ratify crucial international treaties in their election manifesto, namely the International Convention on the Eradication of Racial Discrimination (Icerd) and the Rome Statute on International Criminal Court (ICC).

The ICC provides a significant mechanism as an international court to try “crimes against humanity” such as those committed in the May 13 racial bloodbath of 1969 if only the culprits responsible for orchestrating the pogrom had been apprehended. Unfortunately, those opposing the ratification of the ICC have misrepresented and twisted the role of the ICC, suggesting that the sovereignty of our rulers would be at risk. Such a red herring has no justification in our constitutional pond. To date, 122 countries have signed the Rome Statute of the ICC including Cambodia, Palestine and the Republic of Korea.

Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad has said that ratifying Icerd would entail amending the Federal Constitution and that this is an almost impossible thing to do without a two-thirds parliamentary majority.

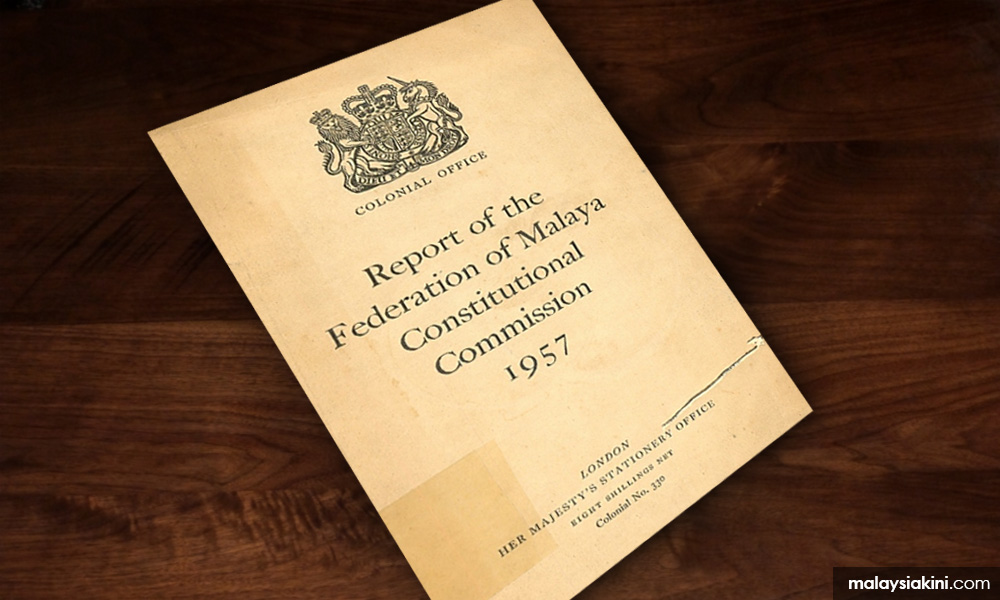

It is a very serious presumption that the Malaysian Federal Constitution promotes racial discrimination and will, therefore, run afoul of the Icerd. When the nation became independent of the British colonial power in 1957, did we really have a social contract that contained elements of racial discrimination? If that was the case, then our founding fathers and mothers were certainly deficient in wisdom and legal nous.

The fact is, our founding fathers and mothers agreed to a federal constitution that did not promote racial discrimination. We should be proud of Part II of the constitution that guarantees “fundamental liberties” for all Malaysians. It includes Article 8:

“Equality. All persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal protection of the law […] there shall be no discrimination against citizens on the ground only of religion, race, descent or place of birth in any law or in the appointment to any office or employment under a public authority or in the administration of any law relating to the acquisition, holding or disposition of property or the establishing or carrying on of any trade, business, profession, vocation or employment […]”

The supposedly “racially discriminatory” Article 153 merely mentions “the special position of the Malays” and that the main purpose for including Article 153 in the constitution was to rectify the perceived weakness of the Malay community in the economic field, the public service and the problem of Malay poverty at the time of Independence. (Tun Mohamed Suffian bin Hashim, An Introduction to the Constitution of Malaysia, KL 1972:245)

The first clause of Article 153 specifically states, “It shall be the responsibility of the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong to safeguard the special position of the Malays and natives of any of the states of Sabah and Sarawak and the legitimate interests of other communities in accordance with the provisions of this Article.” Even so, the Reid Commission had recommended a sunset clause for this “special position of the Malays” of 15 years.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that between 1957 and 1971 there were no complaints of racial discrimination on the scale we have seen in recent years.

It was only after the racial violence of May 13, 1969 fifty years ago that the country was presented with a fait accompli by the new ruling elite in Umno during the state of emergency when in early 1971, they introduced the infamous “quota system” through a new clause (Amendment 8A) to Article 153 in the Constitution (Amendment) Act. Malaysians have lived with a dramatically distorted version of this “quota system” for more than forty years with its continuing negative consequences for many citizens which has generated so much controversy for that length of time.

Strictly speaking, therefore, if we were to go by Umno’s oft-repeated “social contract” at independence in 1957, that “social contract” certainly does not include Clause 8A of Article 153 that was introduced much later in 1971. Even so, if we scrutinise this clause more closely, we will see that it is definitely not a carte blanche for the blatant racial discrimination witnessed in, for example, the quota for matriculation courses and other Mara institutions or the "bumiputera-first" policy at UiTM.

It is also surprising that the lawyers in the country have not ventured an opinion on the applicability of Article 153 to the rampant racial discrimination in “new” Malaysia’s institutions. We have not yet seen a single constitutional lawyer in this country who has dared to boldly state that he or she believes the government of Malaysia is totally justified under Article 153 to have a "bumiputera-first" policy in UiTM. I throw a challenge to any lawyer in this country who dares to make that assertion.

The prime minister must decide if his Harapan government has the political will to progress into the world community that respects all human rights. Ratifying Icerd is a statement to show we consent to be bound to an international treaty that outlaws racial discrimination. Thus, instead of implying that the Malaysian constitution is racially discriminatory, which is not true and is, in fact, scandalous, the prime minister should instead endeavour to enact the necessary legislation to give domestic effect to Icerd.

First and foremost, the Icerd treaty prohibits policies that have a racially discriminatory impact on any sections of people in the country. The prime minister should consult his de facto minister for national unity P Waythamoorthy who has been the best publicist against the racially discriminatory policies in this country in recent years, especially in the UK and the US.

The Icerd treaty requires that victims of discrimination should have a judicial enforcement mechanism available such as an Equality Act and an Equality & Human Rights Commission and the treaty applies to all levels of government – federal, state and local. Out of 197 countries, 179 countries have ratified or acceded to the Icerd. Malaysia is currently one of only 14 countries in the world that have not signed the UN treaty.

When he announced the NEP in 1971, then prime minister Abdul Razak Hussein said the policy would end in 1990. That deadline was ignored and this has become a "Never-Ending Policy" of racial discrimination.

It is high time for a new socially just affirmative action policy based on need or class or sector. Thus, if Malays are predominantly in the rural agricultural sector, we should create policies that benefit the poor farmers and not the rich land-owning class who would also benefit from any “Malays Only” policies. Only such a race-free policy can convince the people that the government is socially just, fair and democratic and walks the talk.

If, as the prime minister says, all the Chinese Malaysians are rich, then what is stopping the government specifying policies that benefit the B40 (ie. based on socioeconomic position) rather than policies that are only for the “Malays”? This question is also asked of the PM-in-waiting, Anwar Ibrahim who has made duplicitous statements on this issue – we cannot have policies which are intended to benefit the B40 but are at the same time, couched in racially discriminatory language for political effect.

Perhaps all politicians in “new” Malaysia should be made to attend “Rehabilitation Classes on Human Rights” where they learn to discard their old racist habits and relearn the politically correct behaviour required in “new Malaysia”.

The lesson of the first year of the Harapan administration is that, as always, civil society needs to be ever vigilant and persistent in pushing for these reforms because the government of the day has shown it is dragging its feet and reneging on these election promises because of “racial” politics.

There have been engagements with civil society but no improvement in promised reform of repressive laws. The cabinet imposed a moratorium on draconian laws including the Sedition Act 1948 and Section 233 of Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) in October 2018. The moratorium was shortlived, and it was lifted in December 2018 following the Seafield temple fracas. Considering the efforts by civil society in contributing to institutional reform after GE14, the prime minister’s decision not to make the Council of Eminent Persons (CEP) report public is unacceptable and stinks of BN non-transparency.

These laws that allow detention without trial violate basic human rights and should be expeditiously abolished. They include the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (Sosma), the Prevention of Crime Act 1959 (Poca) and the Prevention of Terrorism Act (Pota) 2015. The Harapan government is now reconsidering its initial pledge to abolish several contentious laws including the Sedition Act 1948, the Prevention of Crime Act (Poca) 1959, the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971, the Printing Presses and Publications (PPPA) Act 1984 and the National Security Council (NSC) Act 2016.

Such backtracking on the Pakatan Harapan GE14 manifesto is totally unethical and a perversion of human rights.

KUA KIA SOONG is Suaram advisor. The above is his speech at the launch of Suaram's report for 2018 today.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.