COMMENT | April 17 will be a crucial day for Indonesia’s democracy. It is the first nationwide election combining the choice of the president and Members of Parliament at the national, provincial, and district levels.

More than 190 million voters are registered to select the president and Members of Parliament at all three levels.

Sixteen national parties (plus four more local parties in the case of Aceh) are competing for parliamentary seats at all levels. The number of candidates contesting forParliament is not readily available, but is probably in the tens of thousands.

For example, 7,968 candidates across the country (with 40 percent of them being women) are competing for the 575 seats in the national Parliament. While at the provincial and district levels, there are 2,207 seats and 17,610 seats respectively being contested across all 34 provinces.

These are in addition to 807 contenders competing for the 136 seats in the national Senate ‒ or four seats for every one of the 34 provinces. In spite of their size and significance, media coverage of these three levels of parliamentary elections is almost non-existent, since overwhelming attention is directed at the presidential election.

The incumbent president Joko Widodo, nicknamed Jokowi, is once again being contested by the businessperson Prabowo Subianto, a former general of the elite Kopassus force, an Indonesian Army special forces group that conducts special operations missions for the Indonesian government. The two first contended in the 2014 presidential election when Prabowo lost by six percent to Jokowi.

One attraction of Jokowi in 2014 was his humble origin as the mayor of the city of Solo. His success in Solo hypnotised the nation, elevating him to become the governor of Jakarta, then a presidential candidate running on a populist agenda as a ‘man of the people’. This was in sharp contrast to Prabowo (photo), who hails from a distinguished family and was a former son-in-law of the pre-reformist president Suharto.

Although numerous recent polls show Jokowi leading in this election, they also demonstrate his stagnant lead of between 49 to 57 percent, while the trend of his rival continues to strengthen. A great shock came with the release of a poll by the leading daily Kompas at the end of March, placing Jokowi‘s popularity at 49 percent, with Prabowo at 37 percent and 13 percent undecided.

This Kompas newspaper election survey is essential for several reasons. Owned by the Catholic tycoon Jakob Oetama, Kompas is known for its unwavering support of the Jokowi administration, while being seen as less partisan and more objective.

Secondly, this was a unique polling result from a ‘pro-government institution’ compared to the many other polls indicating Jokowi’s huge lead. Such lopsided results led the opposition to label them as ‘cooked polls’ meant to influence voters. Thirdly, the Kompas result appears to confirm Prabowo’s team internal surveys showing that his party has a serious potential for electoral victory.

Much has changed since the 2014 election

What makes the Prabowo team so confident? Much has changed since the 2014 election. Among Jokowi’s signature achievements as President of Indonesia for over four years is the development of much-needed infrastructure, especially outside the main island of Java, including airports, seaports, roads, irrigation and mass rapid transportation.

Jokowi’s team proclaims that infrastructure development will improve connectivity and stimulate competitiveness among the nation’s regions. Thus, the focus of development outside Java, especially in the country’s eastern region, reflects government efforts to improve social justice for all citizens.

Yet this development is not without a price. To meet the nation’s infrastructure needs, the president, along with state-owned companies assigned to perform these tasks, borrowed funds from certain foreign countries.

Large loans from China required Jokowi to grant controversial concessions, including accepting the importation of unskilled Chinese workers. This became a major election issue since Indonesia is a surplus-labour nation with many unemployed indigenous workers.

The inability of the government to explain images on social media highlighting advantages such foreign workers enjoy, has become poisonous for Jokowi this election year. Added to this, the questionable utility of and lack of transparent economic studies on certain massive projects give ammunition to his critics and political opponents.

Jokowi’s overall economic orientation has also been severely criticized. In his efforts to attract investors to support development, the President promotes pro-foreign investment policies and reforms through liberalizing platforms, including the introduction of “sixteen economic reform packages” and “the elimination of 3,000 regional regulations to fast-track licensing processes”.

Although Indonesia has experienced an increase in foreign direct investment, their economic impact remains limited as reflected in modest economic growth of only five percent. This neoliberal policy did not begin with Jokowi, who continues an older policy, yet speeds its process in his obsession to meet the World Bank’s business rankings. Indonesia is now viewed as the World Bank’s failed East Asian miracle.

Today, people are experiencing a high cost of living as the price of fuel and bahan kebutuhan pokok (basic consumption commodities) jumped. To assist in purchasing power disparity, the government introduced cash assistance social security initiatives targeting low-income Indonesians.

Among Jokowi’s new social security programmes introduced during this campaign is the set of three ‘kartu sakti’ (magic cards): a card for inexpensive basic consumption necessities, an unemployment card and a smart card for college education. He also launched Dana Kelurahan (Funds for City Boroughs) as an expansion of the existing Dana Desa (Funds for Villages).

Prabowo’s new economic orientation

While Jokowi’s critics and his political opposition support some of these programmes to help the poor, they view them as camouflage to disguise his macro-economic failings.

They also question the timing of his new proposals, suggesting they were launched to capture votes. Therefore, a large part of Jokowi’s re-election campaign centres on defending his infrastructure projects and economic policies.

Aware of Indonesia’s social and economic conditions, Prabowo made strategic choices in his campaign. His selection of the young and wealthy Sandiaga Uno (photo, former vice-governor of Jakarta, known as Sandi), to be his vice-presidential candidate provides him with a new magnet to attract millennial and business-oriented votes.

Their focus on the economy is proving to be a sensible tactic. Prabowo proposes a new economic orientation termed economi kerakyatan (people’s economy), opposed to the neoliberal scheme of international prescriptions.

This is not new since it is the economic vision of the nation’s founding fathers manifested in the Constitution ─ Prabowo only re-emphasises it. The retired general highlights the necessity of sovereignty (kedaulatan) and independence (kemandirian) in three major areas: food production, energy and water.

Prabowo’s approach is multifaceted, and while dwelling on the economy, he also injects a sense of pride and nationalism. He often repeats the argument: “Indonesia is a rich country but most of its people are poor. Indonesian wealth is flowing overseas ‒ this is unacceptable.”

Prabowo’s economic focus is amplified by his running-mate in more detail. Sandi’s approach takes the form of questioning: “Ladies and gentlemen, millennials: is the price of basic consumer commodities inexpensive? Is your energy bill affordable? Is finding jobs easy?” Sandi promises that with “Prabowo‒Sandi, the cost of basic daily food will be affordable, the price of fuel lowered, and jobs created.”

Sandi also stresses the importance of Micro Small and Medium Enterprises, known in its Indonesian acronym as UMKM. Sandi states these are the nadi (pulse) and driving force of the economy for “99.9 percent of the Indonesian economy comprises these UMKM, and 97.3 percent of our workforce is absorbed by these enterprises. Yet, they have been treated as objects, not subjects [agents] of the economy.”

He promises voters to pay close attention to the importance of these enterprises “making UMKM better, decreasing national debt, and creating successful entrepreneurs.”

While Sandiaga adds economic and youthful credentials to Prabowo, Jokowi’s running-mate Ma‘aruf Amin (photo) was also strategically selected to boost Jokowi’s Islamic qualifications. As a prominent kiyai (Muslim scholar), chairperson of the Ulama Council and Supreme Leader of Indonesia’s largest Islamic NGO organisation Nahdlatul Ulama, Ma‘aruf mitigates the widespread perception that Jokowi is anti-ulama (religious scholars) and anti-Islam.

While the selection of Ma‘aruf undoubtedly repaired Jokowi’s status among his Muslim supporters, other Muslims have not been won over. They argue that “we prefer the candidate selected by the ulama, rather than the candidate selecting an ulama”. This refers to Prabowo, who was approved by the ijtimak (consensus) of the ulama as their preferred presidential candidate.

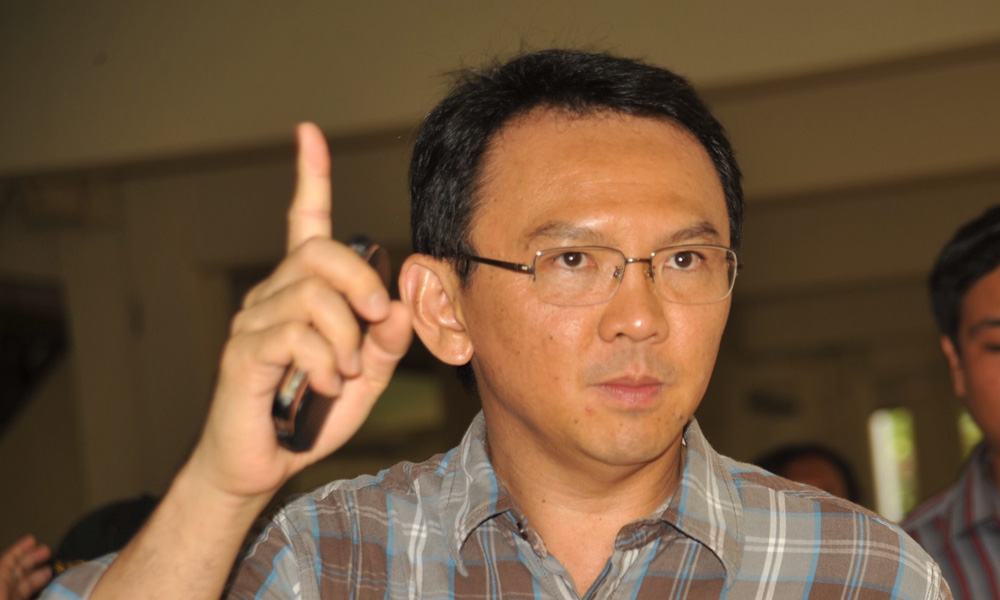

Apart from economic and socio-religious issues, this election exhibits positive and negative symbolic resonances. On the negative side, it is fiercely divisive and awash with political passion, comparable to the effects of the 2017 election for the post of Governor of Jakarta when the incumbent Chinese Christian Basuki Tjahaya Purnama (aka Ahok) was defeated by the Muslim intellectual Anies Baswedan.

Basuki (photo) had been the vice-governor under Jokowi when the latter was the governor of Jakarta. In that hotly contested 2017 gubernatorial election, Anies, with Sandiaga Uno as his running-mate, received the support of Prabowo. In contrast, Basuki was supported by President Jokowi and his ruling establishment.

After his defeat, Basuki was convicted and jailed on a charge of anti-Islamic blasphemy. Echoing those two competing powers of the Jakarta election, a parallel struggle is now unfolding at the national scale with ever more strident passions roiling the population.

Yet this presidential race is markedly different from the Jakarta election for a simple reason: both President Jokowi and Prabowo are Muslims. Unlike Jakarta’s gubernatorial race when a Muslim candidate contested a Christian rival, here two Muslims are contending with each other.

Both men have been attacked on religious grounds by some ideologues: Jokowi was accused of being a communist, and Prabowo linked with the radical Islamic State. These far-fetched accusations reveal the uncultured side of this election.

Sadly, divisions are manipulated by each candidate’s inner circles and zealous supporters. They malign their opponent so that rather than focusing on Prabowo’s or Jokowi’s big ideas and socio-economic programmes for bettering Indonesia, they sling mud at each other’s man.

Media outlets are partly complicit in cheapening the tone of discourse, since most concentrate on simplistic sensationalism rather than informed reporting. In fact, print media and television, as well as the candidates’ inner circles, are so blatantly fomenting lowbrow uncultured partisanship ‒ provoking some citizens to protest by boycotting this election through ‘Saya Golput’ (‘I abstain’).

However, these elections also manifest positive dynamics. There still exist more objective intellectual critics of such political toxicity who seek to uplift the candidates and their ardent followers to a higher discourse of serious political and social responsibility, directing people to choose wisely. This politik akal sehat (sound intelligence politics) casts a refreshing light on the sensational enthusiasm promoted by the candidates’ inner circles and the media.

Another positive aspect is that these elections with numerous local campaigns are treated as festive events by the majority of the candidates’ supporters. There is a flood of participation by citizens who attend rallies in large numbers, many on their own initiative, to celebrate their ‘hero candidate’, hoping he will become their next president.

The 2019 April election campaigns have clearly demarcated the two candidates: Jokowi is a man of action captured in his slogan ‘kerja, kerja, kerja’ (work, work, work), while Prabowo is a man of vision with deep intellectual roots.

This election confirms that Islam continues to be an important marker for Indonesian democracy and social well-being. To become president, the candidate has to be friendly to the majority and the Islamic faith, as well as the other religions.

This election is now too close to call. The winner will be decided by two major factors: which of the two candidates is viewed as a symbol for national and social unity, and as the provider of sound economic stability? Voters will decide in seven days, marking a milestone in Indonesia’s advance toward being a more effective democracy.

DR ASNA HUSIN teaches at Ar-Raniry State Islamic University Darussalam in Banda Aceh. Indonesia. She is currently a visiting researcher at Nonviolence International in Washington DC.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.