SPECIAL REPORT | In the previous segment of this series, we examined the various factors that can compromise the investigation or prosecution of cases where the accused is faced with the death penalty.

Real-life cases, both at home and abroad, have shown that factors such as the work environment and performance pressure of the prosecutors, public pressure, dishonesty or abuse by enforcers, or poor legal representation may lead to a miscarriage of justice.

In some cases, the law does not favour the accused’s pursuit of justice.

Section 37(d) of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 states that “any person who is found to have had in his custody or under his control anything whatsoever containing any dangerous drug shall, until the contrary is proved, be deemed to have been in possession of such drug and shall, until the contrary is proved, be deemed to have known the nature of such drug”.

In other words, there is a “presumption of guilt” instead of “presumption of innocence” behind this provision.

In 2016, a Korean student studying in Malaysia, Kim Yun-soung, was charged after the police found 219g of cannabis during a raid on an apartment in Bandar Baru Nilai.

The inspector with the 10-member police team initially claimed that there was no one else there during the raid, so Kim was the only accused.

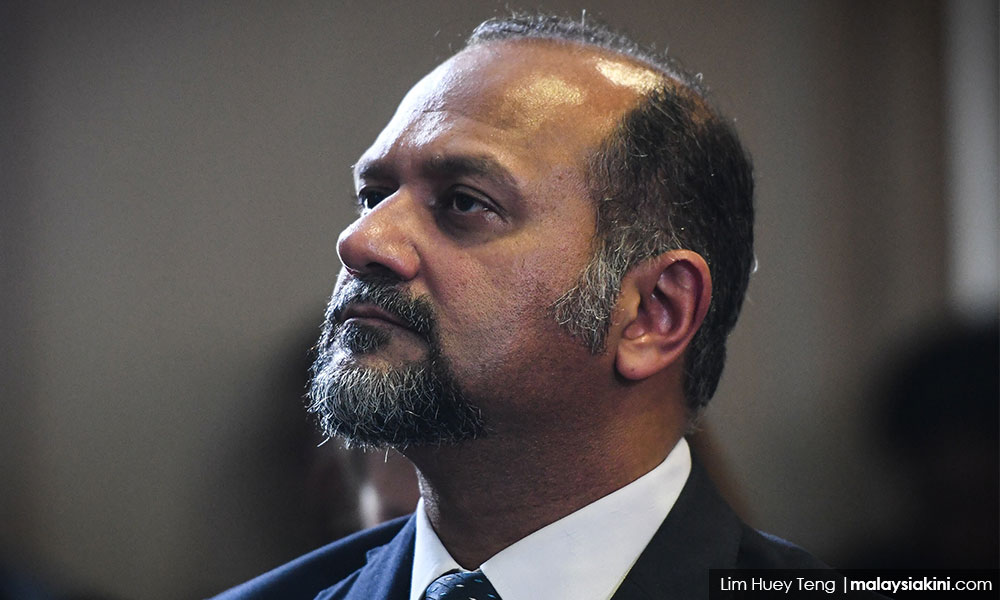

However, when defence lawyer Gobind Singh Deo (photo) said they had a CCTV recording to prove there was another individual in handcuffs present, the police officer admitted to the court that he had lied.

In the end, the 20-year-old South Korean student was acquitted...