COMMENT | Ever since local elections were suspended in 1965 during the Confrontation, with the assurance that they would be restored as soon as peace was declared, the Alliance and subsequently BN failed to do so for 54 years. And now it is Pakatan Harapan’s turn to drag their feet on bringing back elected local governments.

It was clear that the Alliance/BN opted for the convenience of appointing their own political party cronies as councillors, rather than risk the uncertainties of democratic elections. Since 2008, the Harapan government has been following suit in the states they control, namely, Selangor and Penang.

The temptation for any ruling coalition to appoint councillors instead of having them elected into office is certainly strong, since the local tiers of government have been seen as the launch pad for political party appointees as well as their NGO allies all these years.

During the 10 years of Harapan rule in Selangor and Penang, elections could have been held unofficially with the support of civil society and without requiring the Election Commission’s approval.

But political party appointments provide the convenience of perpetuating patterns of patronage. The periodic outbursts of discontent by those party leaders and NGO activists who were overlooked are symptoms of this unhealthy party appointment system.

We can’t afford it?

An elected local government is not some futuristic, utopian ideal that only first world countries can afford. Housing and Local Government Minister Zuraida Kamaruddin said that local council elections might be implemented within three years.

Zuraida (photo) said the Harapan federal government had arrived at the three-year target as it needed to give priority to other important matters, such as ensuring the country was in a stable financial position.

So it looks as though the questionable ‘RM1 trillion national debt’ is now also being used as an excuse to put off the local elections promised by Harapan.

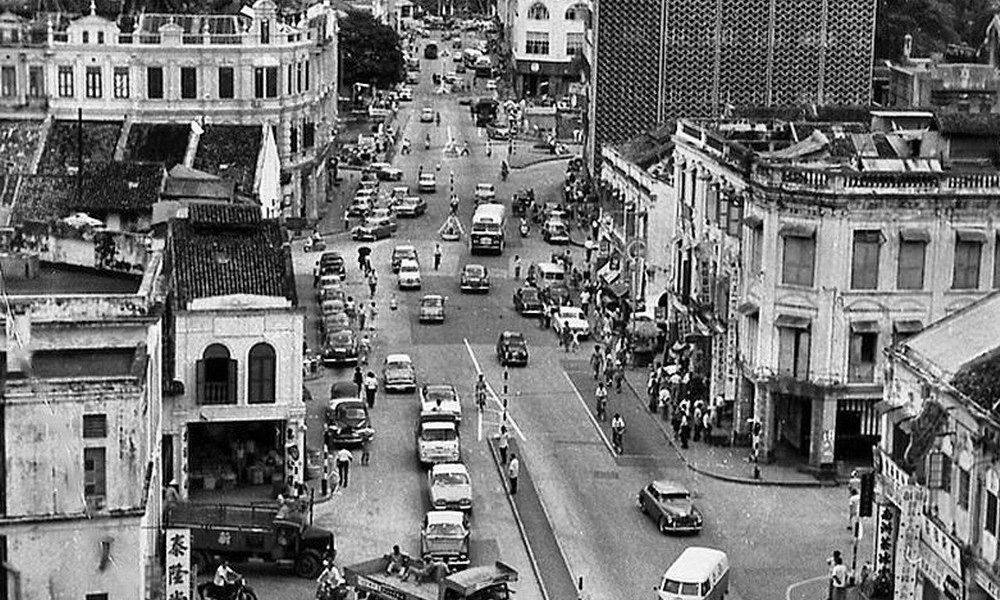

This justification for putting off holding local council elections is laughable when we bear in mind that even before we became independent, we had our very first democratic election – the Kuala Lumpur Municipal Elections of 1952.

It was the first step we took on the way to self-government. At Independence, we continued this commitment to local government elections because appointments to political office were seen as a colonial practice.

This is remarkable, considering how economically poor we were at Independence compared to our economy today. One would expect that as our society becomes more mature in the ‘new Malaysia’, democratic principles of accountability at the local community level would be considered the highest of priorities and the new normal.

Local polls detrimental to race relations?

On April 8, 2017, Dr Mahathir Mohamad was reported as saying that he was not in favour of local council elections, fearing that it would polarise the different races in the country even further.

Mahathir’s reasoning was that since most of the ethnic Chinese were residing in the urban areas, while a majority of the Malays were in rural areas, local elections would see each race governing their own areas.

In fact, during the early years of Independence, the Alliance was reluctant to have local elections because polls in towns and cities tended to be won by the opposition. During the 1960s, many towns and cities were run by the Socialist Front.

This was the real reason for not wanting local elections – not because of the so-called ‘racial divide’. Anyway, Mahathir now heads the old ‘opposition’, so there is no reason to fear such competition.

Furthermore, non-partisan local government is neither unique nor inconceivable. Local government in Malaya before 1960 was not party-based. Many cities around the world, including, for example, some of the largest in the United States, such as Los Angeles and Chicago, have non-partisan elections for their city councillors.

There is no reason why race and religion should dominate, rather than a healthy focus on the welfare and demands of ratepayers.

I have often stressed the fact that an elected local government can, at a stroke, depoliticise education in Malaysia simply by building schools based on need of the local communities – and not to have the Education Ministry treat schools as a political football during general elections.

Few Malaysians have noticed, for example, that the all-important role of local education authorities in the Education Act 1961 is no longer mentioned in the Education Act 1996. Local education authorities serve to allocate funds and other facilities to needy sectors, and can serve to dissipate politicisation of education.

Long overdue

In the democratic tradition, taxation cannot be justified without representation. Ratepayers must be represented on the governing body which determines how that money is to be spent.

This is a fundamental precept of parliamentary governance that is critically applicable at the local government level. It is to satisfy the requirement in a democratic society for greater pluralism, participation and responsiveness.

The 1965 Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Workings of Local Authorities in West Malaysia, led by then senator Athi Nahappan (photo), recommended the return of elected local government. The recommendation was not carried out by the Alliance government, and it proved to be the start of a disgraceful habit by the former ruling coalition of ignoring RCI recommendations.

If we hold fast to the time-honoured concept of no taxation without representation, a nominated local government undermines the legitimacy of local authorities to collect assessment rates, which are the most important source of income of the local authorities. That is why the RCI report concluded that the merits of an elected local government, with all its inherent weaknesses, outweigh those of the nominated ones.

Malaysians are no longer prepared to put up with negligence or irresponsibility. Residents whose voices objecting to crass so-called ‘development’ projects have been ignored, are demanding that their voices be heard at the local council.

In this sense, we can see why local authorities are considered the primary units of government. Many services including education, housing, health and transportation require local knowledge and can be better coordinated and more efficiently implemented through the local authority.

Finally, we find that in the modern state, many social groups such as women and manual workers are grossly under-represented, and local government can provide them with the channels to air their concerns and to participate in decision-making. Generally speaking, bottom-up, local-level participation is vital to ensure voters are able to influence decisions.

So, please Harapan, don’t tell us we can’t have local government elections now because there is no money in the coffers. You simply cannot renege on this election promise. That is totally unacceptable.

KUA KIA SOONG is the adviser of Suaram.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.