The ongoing debate on the future of government-linked companies (GLCs) and their management is complex and multifaceted. These articles contributing to this discussion are based on the third Tun Hussein Onn Chair lecture delivered by Jomo KS, now a member of the Council of Eminent Persons.

COMMENT | Privatisation has been a central pillar of the counter-revolution against government-led economic development from the 1980s. Many developing countries were forced to accept privatisation as a condition for support from the World Bank and other international financial institutions. Other countries, such as Malaysia, have embraced privatisation, often on the pretext of fiscal and debt constraints.

Privatisation usually refers to a change of status from public ownership to private ownership. In Malaysia, and also globally over recent decades, the term is used more loosely. For example, it may only involve minority private ownership after the corporatisation of a state-owned enterprise (SOE), and the sale of a minority share of its stock.

It sometimes also refers to the contracting out of government services to private contractors working on behalf of the government, for example, when allowed to participate in activities previously undertaken solely by the government. The definition is sometimes so broad that it includes cases where private enterprises are awarded licences to participate in activities previously reserved for the public sector.

Strictly speaking, however, privatisation involves the transfer of at least a majority share of a public or state-owned enterprise (SOE) and its assets, or an entity (such as a government department, a statutory body or a government-owned company) previously at least majority-owned by the government, either directly or indirectly.

‘Washington Consensus’

Following the oil shocks of the 1970s, the US Federal Reserve hiked the interest rate to stem inflation in the United States. US President Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker as chairman of the US Federal Reserve in 1980, who presided over raising interest rates, which not only precipitated the fiscal and debt crises of the early 1980s in many parts of the world, especially in Latin America, Africa and Eastern Europe.

The sovereign debt crises forced many countries to seek emergency financial support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, both headquartered in Washington, DC. The IMF provided emergency credit facilities requiring (price) stabilisation programmes to bring down inflation, typically blamed on ‘deficit financing’ due to ‘macroeconomic populism’.

Generally, the World Bank worked closely to provide medium- and long-term credit to these governments on condition that the governments concerned would adopt structural adjustment programmes as well. These structural adjustment programmes generally prescribed economic liberalisation (especially in trade and finance), deregulation and privatisation.

Since then, these international financial institutions have been more powerful in relation to developing countries than ever before. Soon, privatisation became a standard requirement of structural adjustment programmes. Thus, many governments of developing countries were forced to privatise by the (loan) conditions of these programmes.

Many other governments voluntarily adopted such policies as they became standard pillars of the emerging ‘Washington Consensus’ associated with the World Bank, the IMF and the US policy consensus of the Reagan years. Privatisation in developing countries was preceded by the political counter-revolution associated with the election of Margaret Thatcher as UK prime minister Ronald Reagan (below, right) as US president.

Globally, inflation was attributed to excessive government intervention, public sector expansion and SOE inefficiency. It was claimed, with uneven and dubious evidence, that SOEs were inherently likely to be inefficient, corrupt, subject to abuse, and so on.

In Malaysia in the 1970s, the motives of many involved in the preceding public-sector expansion – enabled by high commodity prices and earnings as well as low real interest rates due to easy credit with the need to ‘recycle petro-dollars’ (invest revenues from petroleum exports) – were developmental and noble.

Malaysia embraces privatisation

Looking back at the role of the public sector in Malaysia, it is necessary to consider the changing political circumstances. During the colonial period, the public sector grew primarily to provide infrastructure and services.

Malaysia’s first prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman adopted an essentially laissez faire approach with minimal government interference. Nevertheless, there was some modest expansion of the public sector. For example, Malayan Industrial Development Finance (MIDF) and a number of other similar bodies were created to facilitate early post-colonial economic development ambitions.

From the mid-1960s, many state governments set up state economic development corporations (SEDCs) to enable agricultural and industrial development. Following the first Bumiputera Economic Congress in 1965, private companies were set up to facilitate bumiputera economic empowerment; the most notable included Bank Bumiputera in 1965 and Perbadanan Nasional (Pernas) in 1968.

The 1970s are generally associated with the New Economic Policy (NEP) introduced a year following the race riots after the third general election in May 1969. Leaders like Abdul Razak Hussien, Hussein Onn and Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, his finance minister, saw the public sector as necessary to further national priorities and the public interest, including poverty reduction, ethnic affirmative action and achieving national unity.

Associated with, but distinct from the NEP, was state-led acquisition of economic assets in Malaysia listed on the London stock market. The importance of the nation taking control of its destiny was initially associated with Abdul Razak, and pursued strongly by his successors after his untimely demise in January 1976.

This involved further public sector or SOE growth. There was a strong presumption by national leaders of a shared sense of commitment to the national interest and the public purpose requiring honesty, sincerity and dedication.

Consequently, there was limited recognition of the need for appropriate and adequate checks and balances in those early years despite revulsion of occasional instances of corruption and abuse of the public sector. Hence, the 1970s was an era of rapid public-sector growth, involving SOE expansion and proliferation.

Dr M’s three eras

Mahathir’s tenure as prime minister for over 22 years from mid-1981 arguably involved three eras. The first period, from 1981 to about 1985, was symbolised by his Look East Policy to grow, modernise and industrialise the economy by emulating Northeast Asia, especially Japan and South Korea.

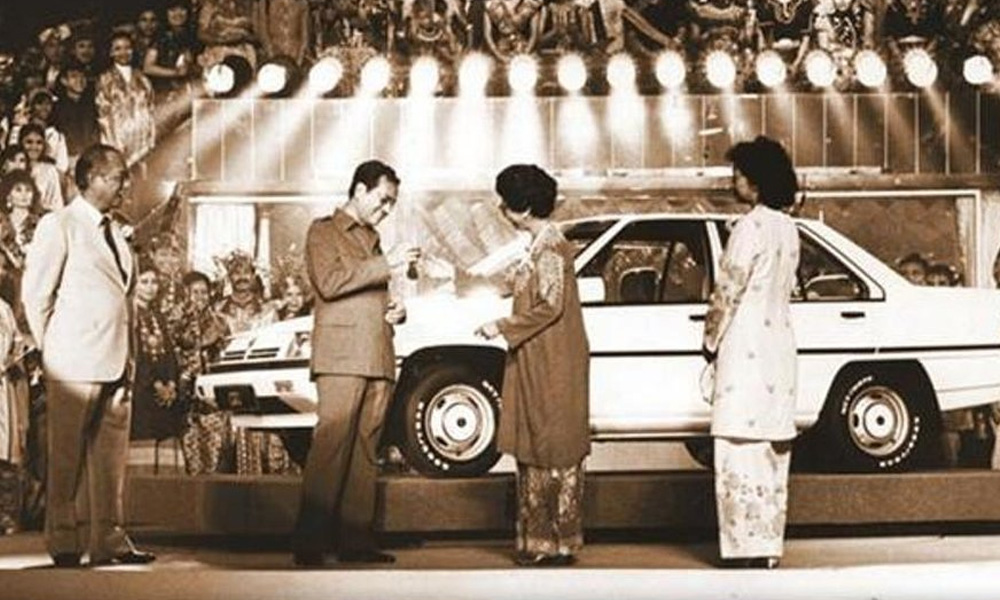

His emphasis on heavy industrialisation involved the establishment of the Heavy Industries Corporation of Malaysia (Hicom) in 1978, when he was minister of trade and industry, with capitalisation from the government. After becoming PM, he pursued the Proton ‘Malaysian car’ project.

His second period saw the reversal of earlier public-sector expansion, especially after he replaced his political rival, Razaleigh, with Daim Zainuddin as finance minister from 1984. Shortly after announcing the Fourth Malaysia Plan for 1986-1990, Mahathir abandoned this approach, and instead selectively adopted economic, cultural and educational liberalisation as well as SOE privatisation and corporatisation.

Thus, unlike many other countries, privatisation was not externally imposed, as Malaysia had not gone heavily into debt, thanks to the availability of windfall earnings from additional petroleum exports.

The third period saw another drastic change of course following the Asian financial crises of 1997-1998. The corporate crises experienced by many private, including privatised corporations, saw some renationalisation, again on generally generous terms, with Danaharta and Danamodal playing crucial roles.

The regime of Abdullah Ahmad Badawi from 2004 saw reorganisation of the SOEs with what is now called government-linked company (GLC) transformation, largely led by his second finance minister, Nor Mohamed Yakcop.

GLC restructuring was quite different from the failed privatisations of the 1980s when many SOEs were turned over to private interests while others were corporatised with greater private ownership. These SOEs were expected to become much more efficient following ownership and accompanying managerial changes. Khazanah Nasional is the archetype of GLC transformation, but other GLCs and government-linked investment corporations (GLICs) were unevenly subjected to some reforms.

Prime Minister Najib Razak’s New Economic Model renewed the promise of privatisation. However, in practice, he emphasised costly infrastructure development involving public-private partnerships (PPPs) – typically involving government debt-financing of private cronies – undermining the thrust of earlier GLC reforms.

Part 2: Is privatisation of Malaysian SOEs good or bad?

Part 3: Has privatisation benefitted the public and consumers?

Part 4: Privatisation: Is the solution worse than the problem?

Part 5: Reforming our government-linked companies

Part 6: Public-private partnerships – the recent fad of PPPs

JOMO KS was economics professor and Assistant Secretary General for Economic Development at the United Nations. He held the chair at the Institute for Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia in 2016-17.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.