Editor’s note: This article by Ooi Kok Hin first appeared in New Naratif as "How Malaysia's election is being rigged" and is reprinted here with permission.

COMMENT | Malaysia’s ongoing redelineation exercise is unconstitutional and will create a Parliament that is extremely unrepresentative of Malaysia’s people, no matter who wins, because it is severely flawed in two main ways: it either creates malapportionment, which is the manipulation of electorate size where one person’s votes become worth up to 3-4 times the votes of another person in a different constituency; or causes gerrymandering, which is the manipulation of electorate composition to the advantage of one party; or both.

Schedule 13 of Malaysia’s Constitution specifically prohibits malapportionment and gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, making the redelineation exercise unconstitutional.

Furthermore, the Election Commission (EC) has broken the law by illegally redrawing the electoral boundaries before the electoral redelineation process had even started, and by illegally breaking up polling districts.

This article explains in detail exactly how and why the redelineation exercise is unconstitutional and illegal.

Background: Redelineation and constitutionality

The general election (Malaysia’s 14th since independence, or GE14) must take place by August 2018. It is likely that new electoral boundaries will be used in the impending general election.

The EC started a delineation review on 15 September 2016, and submitted its final report to Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak on 9 March 2018. This process was rushed and controversial – the Selangor state government filed a legal challenge in October 2016 seeking to nullify the EC’s notice of redelineation, arguing that it violated the Federal Constitution in drawing new electoral boundaries.

Najib will likely table it in Parliament in the March-April session. The redelineation proposal covers both federal and state constituencies and requires the approval of just 50 percent of Parliament, 111 votes, to be passed.

Several commentaries have criticised the redelineation as guilty of ethnic gerrymandering. Focusing on ethnic imbalance, however, not only unnecessarily limits our understanding of the redelineation process, it distracts from the real damage of the redelineation process by using race as a smokescreen.

Looking at this issue through race suggests that there may be winners and losers from this process; in reality, all Malaysians are losers if this redelineation exercise is allowed to proceed unchallenged.

In the election, voters cast two votes: one for representation at the state level (state assembly) and one at the federal level (Parliament). The state constituencies are nested within a larger federal constituency, so it is typical for 3-5 state constituencies to exist within one federal constituency.

Malaysia practices a first-past-the-post system where a simple majority is decisive. No representation is allocated to the losing party, no matter whether they get 49.9 percent or 9.9 percent of the votes cast. This creates vote-seat disproportionality at the constituency level, where 49.9 percent of voters may be against the winner and yet have no representation. This effect is then magnified significantly across constituencies.

This was painfully evident in the previous election (GE13, 2013) where the BN coalition barely squeaked back into power. The opposition won 50.87 percent of the vote, but thanks to shamelessly biased gerrymandering of the constituencies, the BN’s 47.37 percent was sufficient for it to win 133 out of 222 seats (59.9 percent) in Parliament.

As a result, the Parliament was not representative of the people. This disparity between votes obtained versus seats won means that many voters are under-represented or their votes are worthless. It violates a fundamental principle of equality and equal representation (or the “one man, one vote” principle).

Demographic shifts, development and migration change the characteristics of constituencies over time. The Federal Constitution’s Article 113 thus provides for a redelineation exercise, to be done at least eight years after the previous exercise.

The exercise is designed to scrutinise the current population of each constituency and rebalance them, in accordance with principles laid out in the Constitution, aiming for “approximately equal” apportionment and to avoid “vote-seat disproportionality across parties” so that the ballot value of each voter can be equal across all political parties, preserving the principle of “one man, one vote”.

The process begins with the EC informing the prime minister and Parliament and publishing a notice of the First Recommendations for redelineation through gazette and newspapers. After a period for feedback, objections, and inquiries, the EC will revise its proposed redelineation and publicise a Second Recommendations.

Another round of objections and inquiries ensue, after which the EC submits a final report to the Prime Minister to be presented in Parliament. After approval by Parliament, it will be presented to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, who will proclaim an order effective upon the dissolution of the current Parliament.

The Thirteen Schedule of the Constitution details the provisions for a redelineation exercise to be carried out by the EC. In particular, Clause 2 states: "The following principles shall, as far as possible, be taken into account in dividing any unit of review into constituencies pursuant to the provisions of Articles 116 and 117:

(a) While having regard to the desirability of giving all electors reasonably convenient opportunities of going to the polls, constituencies ought to be delimited so that they do not cross state boundaries and regard ought to be had to the inconvenience of state constituencies crossing the boundaries of federal constituencies;

(b) Regard ought to be to the administrative facilities available within the constituencies for the establishment of the necessary registration and polling machines;

(c) The number of electors within each constituency in a state ought to be approximately equal except that, having regard to the greater difficulty of reaching electors in the country districts and the other disadvantages facing rural constituencies, a measure of weightage for area ought to be given to such constituencies;

(d) Regard ought to be had to the inconveniences attendant on alterations of constituencies, and to the maintenance of local ties."

If any of the above principles are not followed – for example, instances of constitutional non-compliance are left uncorrected without due justification, or worse, instances of constitutional non-compliance are aggravated by the changes proposed – then the redelineation exercise would be unconstitutional.

Malapportionment: your votes are not equal

Malapportionment is a manipulation of electorate size, which not only violates the moral democratic principle of “one man one vote” but also violates the constitutional principle spelled out in Thirteenth Schedule 2(c), which states that “the number of electors within each constituency in a State ought to be approximately equal” (with one exception for rural constituencies – see below).

The typical example used to showcase the violation of this “equal apportionment” rule is the comparison between the electorate size of two federal constituencies: Kapar’s 146,317 voters and Putrajaya’s 17,627 voters. But the two federal constituencies do not reside in the same state and Putrajaya, being a separate unit of administration, is an exceptional case.

A stronger case can be made by comparing malapportionment of constituencies in the same state (intra-state malapportionment), in particular because the Thirteenth Schedule 2(c) specifically mentions that the number of electors within each constituency in a state ought to be approximately equal.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at Penang, which is comprised entirely of urban constituencies (examining Penang enables us to make comparisons without the rural weightage clause exemption, which we address in further detail in a separate section below):

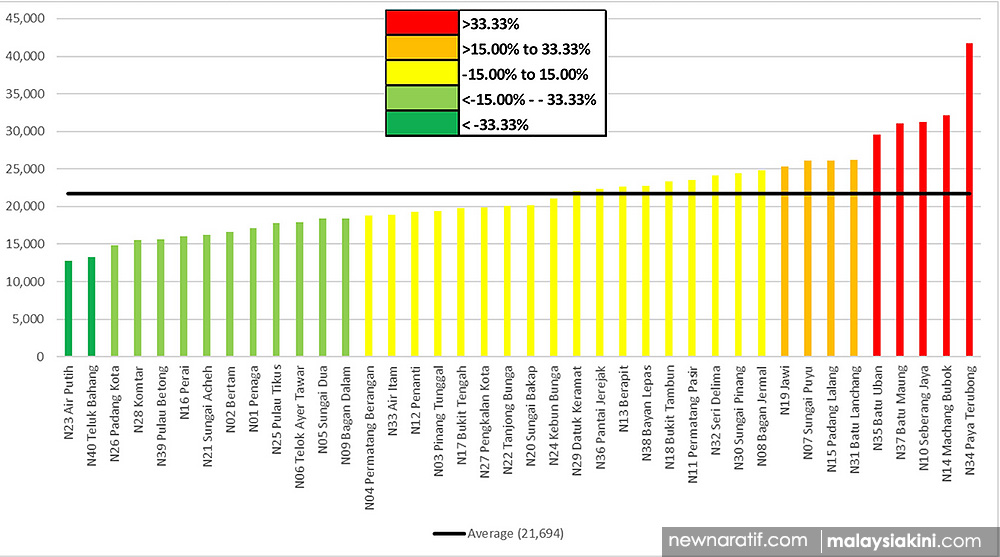

Figure 1: Intra-state malapportionment in the state of Penang. The deviation, in percent, from the average size of the state constituencies (21,694 voters) is denoted by the colour.

Figure 1: Intra-state malapportionment in the state of Penang. The deviation, in percent, from the average size of the state constituencies (21,694 voters) is denoted by the colour.

Severely under-represented constituencies (those with an excessively large electorate, coloured in red) and severely over-represented constituencies (excessively small electorate, coloured in dark green) would have been outright unconstitutional if not for the two constitutional amendments in 1962 and 1973.

Prior to the first amendment in 1962, the permissible range of deviation from the state average was capped at 15 percent. The 1962 amendment increased the range of permissible deviation from 15 percent to 33.33 percent. The cap was entirely removed in the 1973 amendment.

With the removal of quantified criteria, the deviation has skyrocketed from a maximum of 33.33 percent up to 92.25 percent (N34 Paya Terubong in Penang) and above.

In Peninsular Malaysia, the worst case of intra-state malapportionment (by deviation from the state average) is in Johor: 121.66 percent (N48 Skudai). This is a clear violation of the principle of “approximately equal” apportionment.

In Penang, intra-state malapportionment can be most clearly seen by comparing the largest state constituency, N34 Paya Terubong, and the smallest, N23 Air Putih, which are neighbouring and both urban.

Paya Terubong has 41,707 voters, which is more than three times the size of Air Putih’s 12,752 voters. N34 Paya Terubong exceeded the average electorate size in Penang (21,694 voters) by 92.25 percent. Such extreme deviation cannot be justified as “approximately equal”.

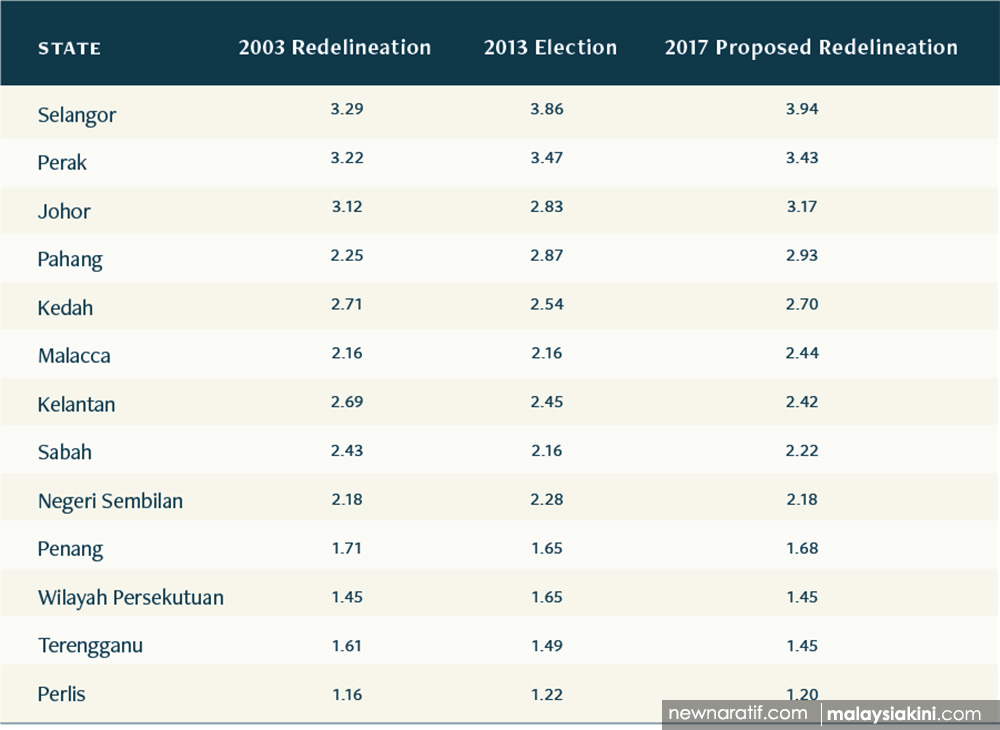

Another way of thinking about intra-state malapportionment is to calculate by the ratio of the largest constituency to the smallest constituency in the same state.

In Selangor, the ratio is 3.94, which means that a vote in the smallest federal constituency (P092 Sabak Bernam) has nearly four times the value of a vote in the largest federal constituency (P109 Kapar) in that same state. In other words, if you vote in P109 Kapar, your vote is worth merely a quarter of a vote compared to a voter in P092 Sabak Bernam.

Table 1: Ratio between largest and smallest federal constituencies in various Malaysian states.

In no fewer than nine states, the ratio of the largest to the smallest federal constituency is more than two. The worst culprits are Selangor, Perak, and Johor. In Perak and Johor, a vote in the smallest federal constituency in each state has three times the value of a vote in the largest federal constituency.

This is a clear violation of the constitutional provision that “the number of electors within each constituency in a state ought to be approximately equal”. While it is possible to argue that the ratio between the largest and smallest federal constituencies in Perlis (1.20 – see Table 1 above) is within acceptable limits of “approximately equal”, the same can’t be said when the population of the largest constituency is more than three times the size of the smallest constituency in Johor (3.17), Perak (3.43), and Selangor (3.94).

The rural weightage clause

Approximately equal apportionment is the rule, but one exception is allowed on the basis of area (land mass), where rural disadvantages are a necessary additional condition.

Section 2(c) in the Thirteenth Schedule says, “…having regard to the greater difficulty of reaching electors in the country districts and the other disadvantages facing rural constituencies, a measure of weightage for area ought to be given to such constituencies".

Since rural areas are harder to access and their populations spread out across large areas, a rural constituency may cover a significantly larger area than an urban constituency in order to have the same number of voters as the urban constituency. However, at some point the constituency may simply get too big to be practical – hence, the rural weightage clause, which grants this exception to permit such a constituency to have fewer voters.

The EC, however, has (mis)interpreted this as “rural weightage” – that rural constituencies should have fewer voters in proportion to urban constituencies, merely because they are rural constituencies, thus giving rural votes greater weight.

This clause pertaining to rural districts has been repeatedly used to justify electoral malpractice. If this rule was applied properly, we should expect all constituencies to have approximately the same number of voters, with the exception of the largest rural constituencies, which would have slightly fewer voters. In other words, the only constituencies that rural weightage should be applied to are the absolute largest constituencies.

In practice, there is minimal correlation between landmass and electorate size – rural weightage is applied to rural constituencies regardless of size.

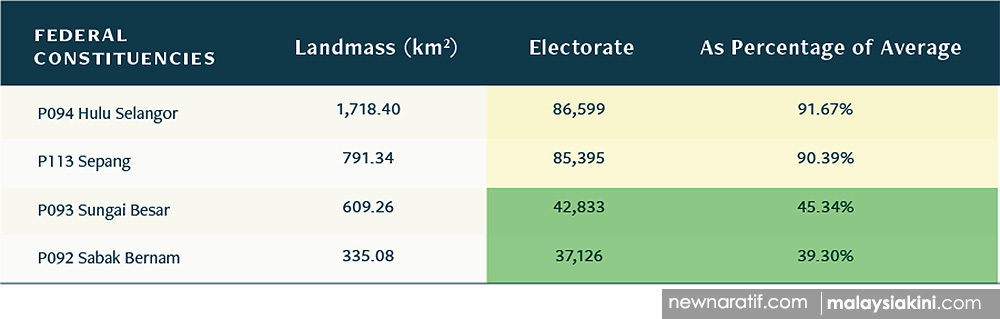

Some of these constituencies are very small. In Table 2 below, which lists four rural constituencies in Selangor, P094 Hulu Selangor and P113 Sepang have the largest land area amongst the four and yet they have electorate sizes that fall perfectly within the acceptable limits (coloured in yellow; less than 15 percent deviation from the state average).

Yet in the same state, we also see the much smaller P093 Sungai Besar and P092 Sabak Bernam (the state’s smallest). If we combined P093 Sungai Besar and P092 Sabak Bernam, we would have a single constituency with 79,959 voters, which would be approximately 85 percent of the state average but in an area still only 55 percent the size of P094 Hulu Selangor. There is no basis, therefore, for P092 and P093 to be separate constituencies.

Table 2: Comparison of four rural constituencies in Selangor.

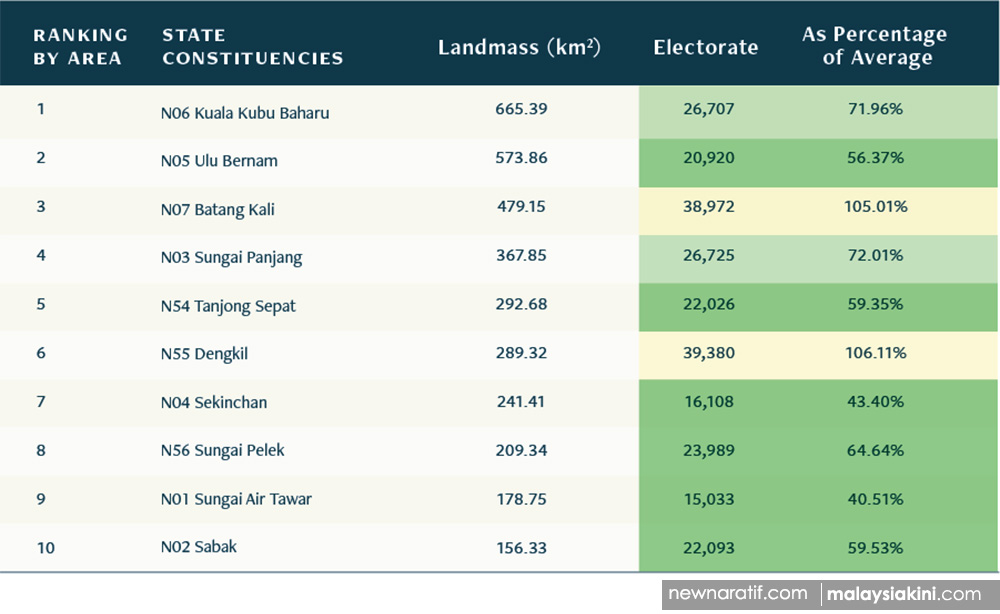

This misapplication of rural weightage can also be seen in state constituencies. In Table 3, the three state constituencies of N06 Kuala Kubu Baharu, N05 Ulu Bernam, and N07 Batang Kali, are the largest in Selangor (by land area).

If the third largest, N07 Batang Kali, could have an electorate 5 percent larger than the state average, there is no justification for any of the smaller constituencies to be eligible for rural area weightage.

N01 Sungai Air Tawar (the state’s smallest constituency) simply cannot be eligible for rural weightage as it has less than half the electorate of N07 Batang Kali when the latter has more than twice its landmass.

Table 3: Comparison of state constituencies in Selangor by land area.

Likewise, while the rural clause justifies an exception for some rural areas, it does not justify the under-representation of urban areas. Thus, Section 2(c) cannot be used to justify excessively large constituencies – of which there are many.

Referring back to Figure 1, the excessively large constituencies in Penang (coloured in red – N35 Batu Uban, N37 Batu Maung, N10 Seberang Jaya, N14 Machang Bubok, and N34 Paya Terubong) all deviated from the state average by more than 33.33 percent.

The clause is meant to ensure representation for rural voters and may make exception for a rural constituency small in electorate size but does not justify excessively large urban constituencies. Doing so is amounting to reducing representation for the voters in those areas.

Gerrymandering: Manipulation of electorate composition and severance of local ties

Gerrymandering is a manipulation of electorate composition to the advantage of one party. By deliberately arranging the constituency to advantage one party, gerrymandering enables politicians to choose their voters rather than the other way around.

This is particularly effective in “First Past The Post” systems, because (as noted above) of the “winner-take-all” nature of the system. The gerrymander only has to redistrict a small number of voters in order to win a seat; do this a few times and you produce a massive swing in the number of seats won. Because the changes can be very small, but the gain from cheating very high, it is very lucrative for parties and politicians to engage in it.

The constitution’s Thirteenth Schedule 2(d) provides safeguards against gerrymandering by specifying that “regard ought to be had to the inconveniences attendant on alterations of constituencies, and to the maintenance of local ties.” Put simply, a constituency should represent an actual community of common interests, and not an arbitrary collection of citizens.

“Inconveniences” arising from the alteration of constituencies (including those arising specifically from the severing of local ties) can be grouped into three types:

- Type 1: Constituencies unnecessarily cutting across local authority areas, causing municipalities or districts to be fragmented.

- Type 2: Electoral boundaries cutting through and breaking up local communities or neighbourhoods.

- Type 3: Constituencies combining communities with few ties and few common interests.

All three types of gerrymandering fail to adhere to the constitutional stipulation that electoral constituency should, as far as possible, maintain local ties.

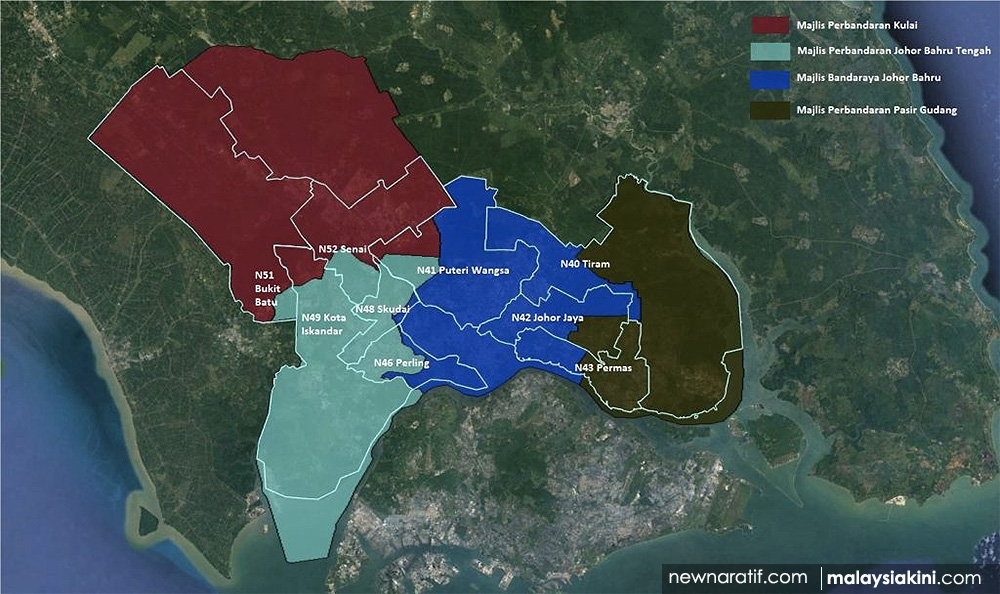

Gerrymandering Type 1 involves constituencies that cross several local authority areas (local council, or Pihak Berkuasa Tempatan, PBT). The map below demonstrates cross-local authority areas in Johor that are constitutionally non-compliant with 2(d) in Thirteenth Schedule of the constitution. State constituencies cut across the jurisdictions of multiple local authorities (represented by the colours).

Map 1: State constituencies (represented by the lines) in Johor state which cut across multiple local authority areas (represented by the colours).

In the example above, the state constituency N41 Puteri Wangsa (centre in the map) in the state of Johor incorporates sections of three separate local authorities: Majlis Perbandaran Kulai (Kulai Municipal Council, in red), Majlis Perbandaran Johor Bahru Tengah (Johor Bahru Tengah Municipal Council, in green), and Majlis Bandaraya Johor Bahru (Johor Bahru City Council, in blue).

Constituencies that cut across two or more local authority areas create unnecessary complications that inconvenience both the voters and elected representatives. The voters in the same local authority area are likely to share common interests and live in the same neighbourhood, and form a logical single constituency. A constituency that cuts across multiple local authorities represents an arbitrary combination of communities with distinct interests, and forces the elected representative for the constituency to work with multiple local authorities to solve problems.

Gerrymandering Type 2 involves breaking up communities/neighbourhoods that share common interests and background.

Neighbourhoods are cut up in oddly shaped boundaries and voters living in the same residential area find themselves voting in separate constituencies. To pick one example, the neighbourhoods between the constituencies of N44 Larkin and N45 Stulang (Map 2) found themselves partitioned by a zig-zag boundary drawn by the EC.

Map 2: Boundary between two state constituencies in Johor state.

Zooming into the highlighted area, Map 3 shows the boundary should have been drawn as a straight line down the highway (Lebuhraya Tebrau). But instead, the EC draws a sharp turn into Jalan Dato Abdullah Tahir, then again at Jalan Dato Sulaiman, creating a zig-zag separating Taman Abad from their neighbouring communities.

Map 3: Close-up of the boundary between two state constituencies in Johor state showing divided communities.

If the EC had drawn the boundary down the highway, the Taman Abad, Yahya Awal, and Wadi Hana communities on the left side of Lebuhraya Tebrau would be grouped into the same constituency, while the Taman Maju Jaya communities on the right side of the highway would be grouped into another constituency. The current proposal puts neighbourhoods on the same side of the highway in two different constituencies, and neighbourhoods on different sides of the highway in one constituency.

Map 4: Arbitrary partitioning of townships of Banting and Jenjarom between three state constituencies. Click on the image for a larger view.

Another example can be found in Map 4 above. The townships of Banting and Jenjarom are arbitrarily partitioned in zig-zag style between N51 Sijangkang, N52 Banting (now renamed Teluk Datuk) and N53 Morib. The arbitrary zig-zags appear to be motivated by gerrymandering.

The deliberate movement of voters saw N52 Banting receiving 5,760 electors from N53 Morib and 4,804 electors from N51 Sijangkang, who are mostly Chinese and expected to be pro-opposition while 7,365 electors – mostly Malays and expected to be supportive of the ruling regime – are transferred from N52 Banting to N51 Sijangkang.

While three constituencies were previously won by the opposition, these changes result in the packing of N52 Banting into a super-stronghold for the opposition party DAP and cracking of N51 Sijangkang and N53 Morib to make them more winnable for the United Malays National Organisation (Umno).

Gerrymandering Type 3 involves arbitrary grouping of communities which have minimal common interests into one constituency.

Map 5: Misallocation of Pulau Ketam into N45 Selat Klang instead of N46 Pelabuhan Klang.

A clear example is Pulau Ketam (highlighted areas in Map 5) in the state of Selangor. Grouping the Pulau Ketam community with the urban strip (into N45 Selat Klang) has had serious implications for the electors in real life.

As Pulau Ketam islanders make up only 13 percent of the state constituency, they complain of being neglected by the elected representative, who naturally focuses her energy on the 87 percent majority on the mainland, which has no social or economic ties and few common interests with the islanders.

This negligence is magnified at the federal level as the 4,770 electors on the islands constitute an even tinier minority, just 3 percent in P109 Kapar (146,317 electors), the nation’s largest constituency in terms of number of voters.

The Pulau Ketam community should have been incorporated into N46 Pelabuhan Klang as its economic and social activities are closely tied to the maritime township of Port Klang and by extension, the Klang town. The EC’s failure in making such an intuitive correction preserves non-compliance with the Constitution, defying the purpose of a delimitation review under Article 113(2).

Hidden hands: Exclusion from redelineation and illegal changes

In many cases, extreme malapportionment and gerrymandering of constituencies already exist, and yet not corrected as the constituencies are excluded from the redelineation exercise i.e. when no changes are proposed. In the current redelineation exercise, not all constituencies will have their boundaries redrawn. Many constituencies have been excluded and will be left untouched.

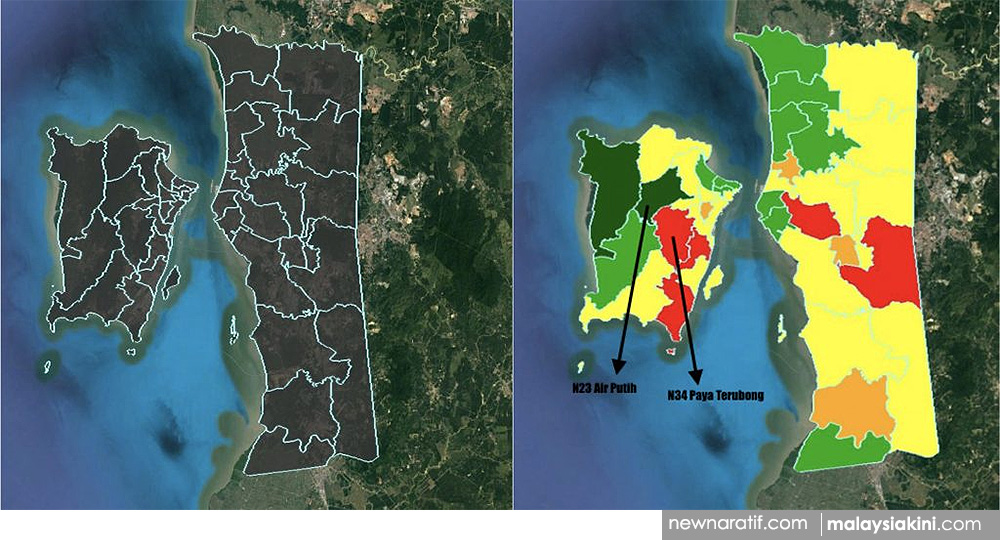

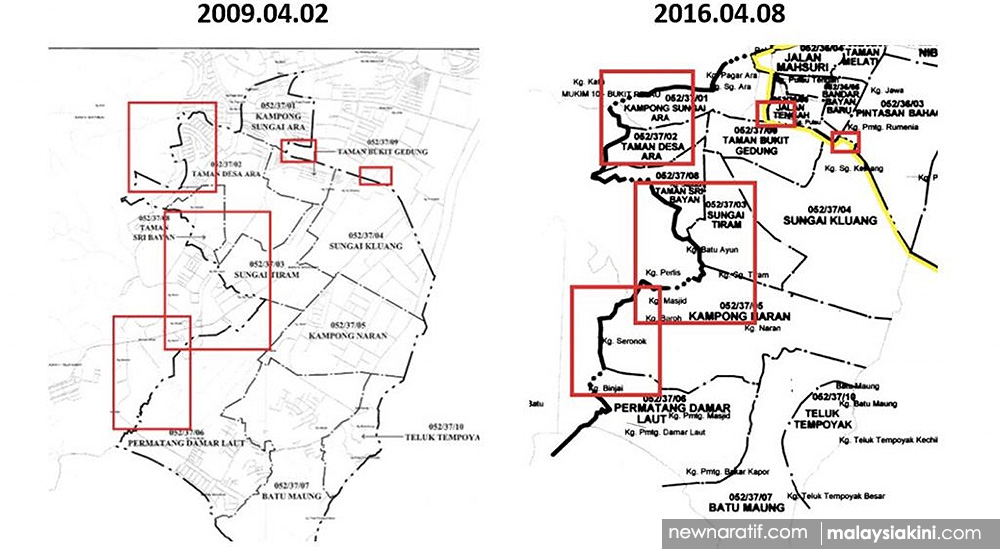

Map 6: State constituencies in Penang state.

On the left, Map 6 shows the state constituencies in Penang which are entirely excluded from the redelineation exercise. No justification for their exclusion has been provided.

On the right, Map 6 shows the levels of malapportionment in the same state (the colour-scheme being identical as Figure 1). Given the severity of intra-state malapportionment in Penang, there is no reason why these constituencies should be excluded.

There are two severely over-represented state constituencies (dark green in colour) and five severely under-represented constituencies (red in colour).

Their exclusion from the redelineation exercise is baffling because the existing malapportionment is severe. The EC is failing to perform its duty, as mandated by the constitution, to redelineate to correct extreme malapportionment.

Logically, N34 Paya Terubong (red, centre of Penang Island) should have ceded some of its voters to N23 Air Putih (dark green, directly on top of N34 Paya Terubong). Since the former is excessively large, the latter excessively small, and they are next to each other, it is a straightforward change.

This failure to correct an obvious violation of the constitutional principle laid out in the Thirteenth Schedule is unconstitutional. The Election Commission fails its duty by excluding these constituencies from the redelineation review.

This is not an exception. The exclusion of constituencies is widespread. At least 96 federal constituencies and 246 state constituencies are excluded from the redelineation proposed by the EC, thus sustaining pre-existing malapportionment and gerrymandering and defeating the purpose of the redelineation exercise.

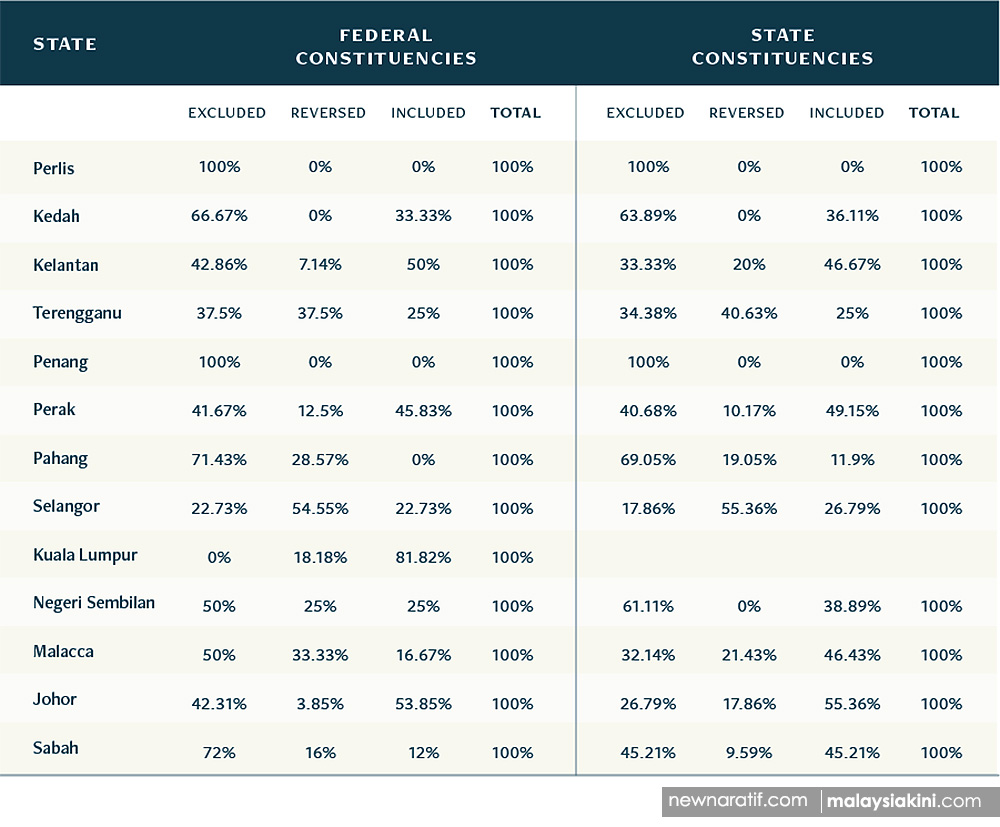

Table 4: Exclusion of constituencies up to 2nd Recommendations. “Excluded” refers to the constituencies that are excluded from the redelineation exercise (no changes proposed), “Reversed” refers to constituencies with changes proposed in the 1st Recommendations but reversed in the 2nd Recommendations (changes are cancelled, so ultimately no changes proposed), and “Included” refers to constituencies which are included in the redelineation exercise.

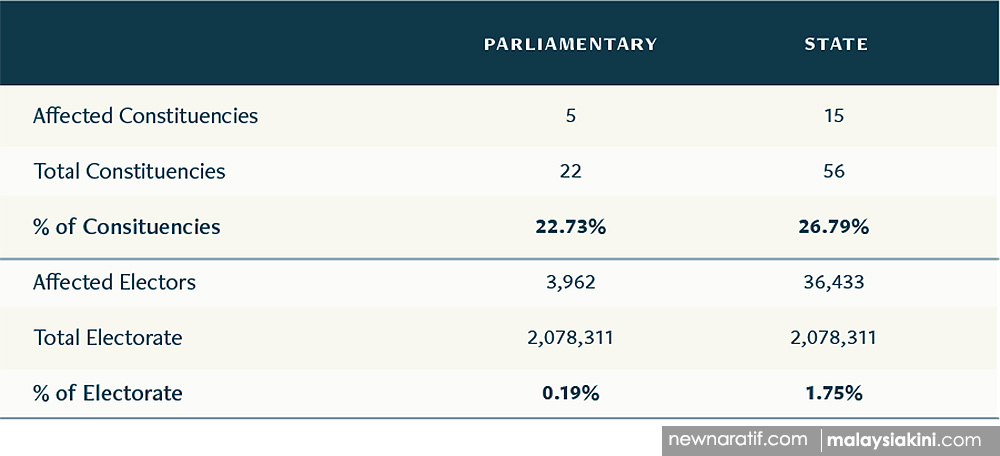

The exclusion viewed in terms of actual numbers of voters that are moved is even more dramatic. In the state of Selangor, despite significant malapportionment and gerrymandering in the existing constituency boundaries, only about 2 percent of voters will actually be moved in the redelineation proposal.

Table 5: Number of voters that are actually moved in the state of Selangor after the 2nd Recommendations proposed by the Election Commission.

But does the EC really not change the boundaries of these excluded constituencies? Shockingly, unconstitutional pre-delineation changes (changes which are not part of the redelineation exercise) are also being made to polling districts and electoral boundaries!

Map 7: Boundaries of N37 Batu Maung state constituency in Penang state.

Map 7 shows that the boundaries of a state constituency in Penang, N37 Batu Maung. The boundaries are demonstrably different between the years 2009 and 2016, despite the Election Commission’s exclusion of N37 Batu Maung from the redelineation exercise.

The only explanation is that the changes were discreetly made by the EC prior to the commencement of the redelineation exercise. An estimated 96 percent of the federal constituencies in Perak, 77 percent in Johor, and 69 percent in Penang are affected.

These pre-delineation changes effectively render the redelineation exercise meaningless as most changes were introduced before redelineation. More importantly, because they are not done in accordance with the procedure for changing electoral boundaries spelled out in the constitution, any pre-delineation exercise changes are therefore unconstitutional and illegal.

Another sneaky change made by the EC is the breaking up of polling districts. This was done during the redelineation exercise but is no less illegal.

The EC is empowered to alter the division of a constituency into polling districts under the Election Act 1958. The EC may move polling districts into different constituencies, but it does not have the power to divide one polling district into two polling districts scattered across two constituencies.

Additionally, the EC must use the same electoral roll throughout the redelineation process. By altering polling districts in the delineation process, the EC has directly violated Section 3 of the Thirteenth Schedule which reads, “For the purposes of this part, the number of electors shall be taken to be as shown on the current electoral rolls”.

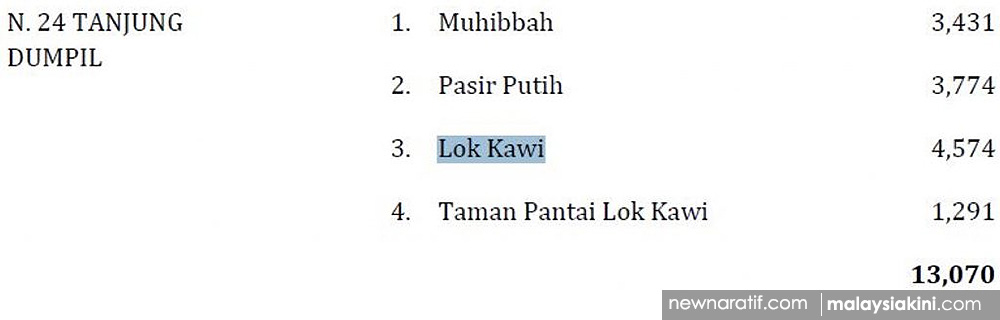

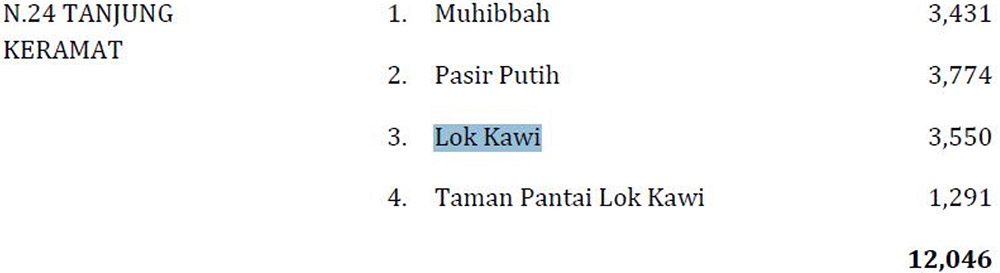

In Sabah, the number of voters in the polling district named Lok Kawi under the state constituency N24 Tanjung Keramat (previously named N24 Tanjung Dumpil) is noticeably different. It was split from 4,574 voters into 3,550. The difference (1,024) was transferred to another state constituency, N23 Petagas.

Figure 2: Polling district Lok Kawi in September 2016 when the EC publicized the 1st Recommendations.

Figure 3: Polling district Lok Kawi in March 2017 when the EC publicised the 2nd Recommendations.

In N23, two polling districts (Sailan and Putatan) were renamed and reconfigured with the additional 1,024 voters from N24 to become three new polling districts.

This is procedurally wrong but also has real consequences for the voters. The original 4,574 voters would not know which constituency they would be in (one of the 3,550 who stay put, or one of the 1,024 who were moved) because there are no new polling district maps to inform them – new polling district maps are normally issued alongside new electoral rolls.

In any event, the EC must use the same electoral roll throughout the entire redelineation exercise. When they break up a polling district, they have altered the electoral roll, thereby making the redelineation exercise unconstitutional as per Section 3 of the Thirteenth Schedule.

Conclusion: Demand electoral system reforms

The redelineation proposed by the EC severely violates the provisions contained in the Thirteenth Schedule of Malaysia’s Constitution. Consequently, the entire redelineation exercise is unconstitutional. Worse, the outcome of GE14 will certainly not be genuinely representative of the Malaysian people.

As things stand, the legal avenues to challenge the redelineation exercise have almost been exhausted.

Multiple legal challenges by the Selangor state government, Penang state government, and members of the public have been unsuccessful.

Activists and a former senior judge expressed disappointment over the Federal Court’s ruling. The EC rushed to submit the final recommendation to the prime minister, who will table it in Parliament very soon.

Electoral watchdog Bersih 2.0 has called for a Royal Commission of Inquiry (RCI) on the electoral system. The RCI can investigate and propose reforms to the electoral system, promote vote-seat proportionality and political inclusion of all communities and segments in Malaysia, and reform the Election Commission.

The ruling BN has stonewalled Bersih 2.0’s demand for free and fair elections. The best hope for implementing this RCI is the opposition coalition, Pakatan Harapan, led by former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad. The coalition’s recently launched election manifesto is promising, with institutional reforms on the cards, but stopped short of pledging electoral reform and local election.

With recent court decisions rendering objections to the proposed redelineation all but moot now, existing malapportionment and gerrymandering will not be corrected.

It will be at least eight more years till the next redelineation exercise. If the next incoming government is serious in cleaning up malapportionment and gerrymandering, proper diagnosis of and reforms to the electoral system are necessary. The RCI, which can be immediately convened, is a big step forward to that direction.

Good, honest governance requires genuine accountability from our elected politicians. Accountability requires free and fair elections. Free and fair elections can only happen in the absence of malapportionment and gerrymandering, with redelineation carried out in accordance with the constitution and in obedience with the law.

For reforms to happen, it is paramount for the Malaysian people and interest groups to demand electoral system reforms and exert influence on politicians to act and put electoral system reform on their agenda.

OOI KOK HIN is an analyst at the Penang Institute.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.