Editor’s note: This is part two of a series on the Malaysian labour movement.

FEATURE | The fact that the Malaysian trade unions movement played a significant role in the political, economic and sociocultural life of Malaysia has been forgotten by many.

The labour movement did actively struggle for independence from the British colonial powers, and contributed significantly even in the determination of the future of Malaysia, including the drafting of the Malaysian Constitution.

But alas, all that is in the past, and the trade unions have been systematically weakened and isolated from involvement in the life of the nation, first by the British colonial masters and thereafter by the Umno-led coalition that has governed Malaysia since independence.

This weakening, nay, annihilation, of the labour movement still continues today through the actions and omissions of a government that seems to not just have embraced neoliberalism, but is also seen today as being pro-business. Of late, government-owned and controlled companies also are seen to be violating worker rights.

The future of the labour movement in Malaysia now depends on the workers and the trade unions, who really must appreciate the history of the Malaysian labour movement and decide whether they would want to struggle to make the labour movement once again strong and relevant, or just allow the slow withering away of not just the movement, but also worker and trade union rights.

Origins of union: Protection and promotions of rights

A worker alone is weak, but workers united are strong. Workers have always naturally come to a realisation that only together as workers will they be able to fight and get better rights and justice at their workplace. As such, more likely than not, there have been organised worker solidarity actions in one form or another ever since there have been workers in Malaysia.

For Malaysia, the advent of worker struggle would have been in the rubber plantations and the tin mines (photo), whose labour was primarily workers of Indian and Chinese origins – a reality then when Malay workers resisted working in such mines and plantations, choosing rather self-employment, small businesses, farming, fishing and the civil service. The majority of the workers in the civil service were Malay.

The origins of organised labour in the form of worker unions in Malaysia date back to the 1920s. Workers then, who were primarily of Chinese and Indian origins in the private sector and Malay workers in the civil service, formed what was known as General Labour Unions (GLUs).

GLU membership was generally open to any worker, with no restrictions with regards to any particular industry, sector or workplace, unlike what we have today in Malaysia.

GLUs were generally formed in different geographical areas all around Malaya. They attracted many workers and were strong. In the struggle for rights, history shows that many actions were taken by GLUs, including strikes.

The labour movement then was not restricted to merely employer-employee matters, but also played an active role in the political, economic and sociocultural lives of the country.

The labour movement, together with other pro-independence groups (photo - MPAJA), was also actively involved in the struggle for independence from the British. They were also active in the struggle against Japanese occupation forces during World War II.

An example of a union then was the Selangor Engineering Mechanics Association, which was registered in 1928, and was maybe one of the first registered trade unions in Malaya.

The GLUs and many of the unions also started coming together as coalitions and federations – and finally merged into the Pan-Malayan General Labour Union (PMGLU) and the Singapore GLU.

British moves to weaken labour movement

The British colonial powers, worried about the growing labour movement, decided to try to control and influence it. The British colonial government were especially concerned about the perceived influence that the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and other pro-independence groups had in the labour movement.

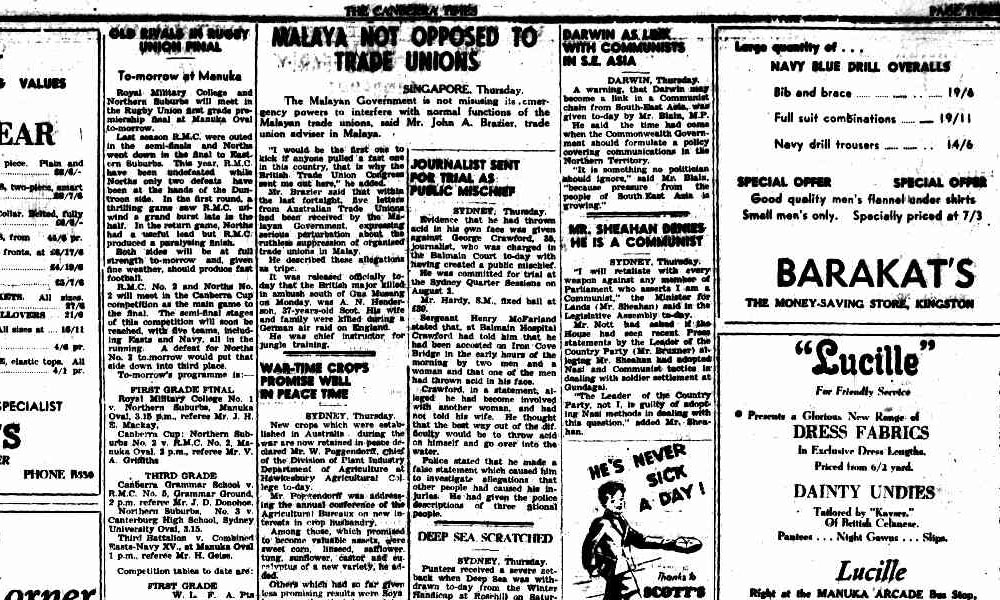

Methods the British employed to weaken and control the labour movement included the enactment of laws like the Trade Union Ordinance of 1940, and the appointment of the Trade Union Advisor.

One of the primary objects of this Trade Union Ordinance was to stabilise the labour situation in the interest of increasing production to sustain Britain's economy and its war efforts. It was not concerned about worker or trade union rights.

The Malayan economy at that time was geared to support the wartime needs of Britain. As such, labour and trade union rights, and existing struggles for better rights had to be suppressed and subordinated to what the British considered more important – Imperial Defence.

Malaya then was considered the “dollar arsenal” for the British empire, and the 1940 Ordinance was enacted for the purpose of ensuring a continued flow of revenue to the British Empire.

The stated object in the title of this 1940 Ordinance was, “An Enactment for the Registration and Control of Trade Unions''. Its declared purpose was the fostering of “the right kind of responsible leadership amongst workers and at the same time to discourage or reduce such influence as the professional agitators may have had and to reduce the opportunities or the excuse for the activities of such persons.''

It was clearly to weaken the existing labour movement, and transform existing trade unions and union leadership into what the British wanted.

The existing worker solidarity was to be destroyed, and a “divide and weaken” policy was the aim. Private sector workers were to be separated from public sector workers, and workers from different industry and sectors were to be kept apart.

The role of unions were to be limited to simply “industrial relations” matters – matters between workers and employers only. Unions were no longer allowed to be involved in matters concerning the nation, including the struggle for independence.

This new Trade Union Ordinance now required unions in Malaya to be registered (or rather re-registered), which meant submitting an application to the government, and receiving government approval prior to registration. This allowed the government not to re-register some of the stronger unions, and federation of unions across different sectors or industries.

As such, the new law prevented government (or public sector) employees and private sector employees from belonging to the same union. The affiliation of unions with other classes of unions was also prevented. Restriction was also imposed on the usage of union funds.

The registration rules were somewhat restrictive. For instance, government employees and non-government employees could not anymore belong to the same union or even to affiliate themselves with unions of other classes of workers. The usage of union funds was also restricted - it could no longer be used for a variety of other purposes, including political purposes.

Under these rules, all the existing GLUs (or even other federations of unions across different sectors, industry or occupation) were not qualified for registration and therefore could no longer operate legally.

The new Trade Union Ordinance and laws that came into force in 1946 effectively killed the GLUs, which could no longer be registered (or re-registered) under the new law, and as such were no longer able to operate legally. It also killed off many stronger unions.

What is of interest was that this new policy and laws did not apply to the union movement in Britain and the UK. It only applied to Malaysia. British unions to date are still involved in political struggles, and even political parties like the Labour Party, in the UK.

Part 1: The state of the labour movement in Malaysia

Part 3: How the British suppressed the Malayan labour movement

Part 4: The last breath of the labour movement?

This article was first published by Aliran here. Malaysiakini has been authorised to republish it.