The Penang floods last weekend have been described as unprecedented, triggered by the heaviest rainfall in the state’s history.

Things got so bad that Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng reached out to Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi for military aid in flood relief efforts, and the former even made an emotional video describing the dire situation in the state.

The death toll in the Penang floods has been confirmed to be at least seven so far. Many Penang residents have also been uprooted from their homes and are currently seeking shelter in relief centres.

Unfortunately, this disaster could potentially be a sign of things to come, with climate change becoming a hot topic again since the United States was battered by a series of hurricanes earlier this year, such as hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria.

In a report by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), it is stated that tropical atmosphere generally holds more water vapour due to climate warming and that this higher water vapour content leads to higher rainfall rates during hurricanes, such as Hurricane Harvey.

It was also reported that an Asian Development Bank study revealed that Southeast Asia will be hit particularly hard by climate change.

Though the study focused on Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, it said that their coastal populations face rising sea levels.

Malaysia has long enjoyed a certain protection from natural disasters due to our location, but now, Penang, as a coastal area, could potentially face many of the same problems as our neighbours in the future, due to climate change.

What this means is that the recent floods in Penang might not be a one-off incident.

Climate change is real and we need to be just as prepared as the rest of the world in dealing with its consequences.

While recovery and relief efforts are still ongoing in Penang, it might be wise to look further ahead and start planning for disaster risk mitigation and awareness in the future.

Malaysia would be wise to look to Japan to see what the East Asian country has done in this regard.

Japan's own disaster

In 2011, Japan’s Tohoku region experienced the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan, at 9.0 to 9.1 magnitude on the Richter scale. This earthquake triggered powerful tsunami waves that reached heights of up to 40.5 metres.

The devastation was large-scale, with many lives lost and buildings destroyed. The Japanese National Police Agency report confirmed that there were 15,894 deaths due to this disaster.

But the death toll could have been much higher, as I learned during a recent trip to the Tohoku region in Japan.

As part of the 2017 Jenesys programme with a focus on media, which is advanced by the Japanese government, we visited the Arahama area, a small town in Tohoku, located along the coast, which was heavily affected by the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami.

We visited the Arahama elementary school, the only major building left standing in the area after the disaster, and learned that it was an evacuation centre for its surrounding area during the earthquake and tsunami.

The four-storey reinforced concrete school building was the refuge for 320 residents, students and school personnel on March 11, 2011, when the disaster struck.

All of them had had many drills prior to the disaster, as well as information provided to them, about their respective evacuation centres and the evacuation protocols, which made the process on that day, a lot faster and smoother.

This is something that Malaysia should emulate, as currently we only have evacuation drills within buildings. Most Malaysians probably do not know their nearest evacuation centres in the case of emergencies, which is a major oversight in disaster preparation.

The deputy chief of the Malaysian mission to Japan, Asri Mat Yacob, told Malaysian journalists that the Japanese have emergency drill after drill after drill, unlike Malaysia.

Asri also expressed the sentiment that this is a practice Malaysia needs to adopt, to prepare for natural disasters.

Learn from the past

On March 11, all 320 of the evacuees at the school survived as the quick-thinking principal had instructed everyone to evacuate to the fourth floor or the roof once the tsunami warning was issued.

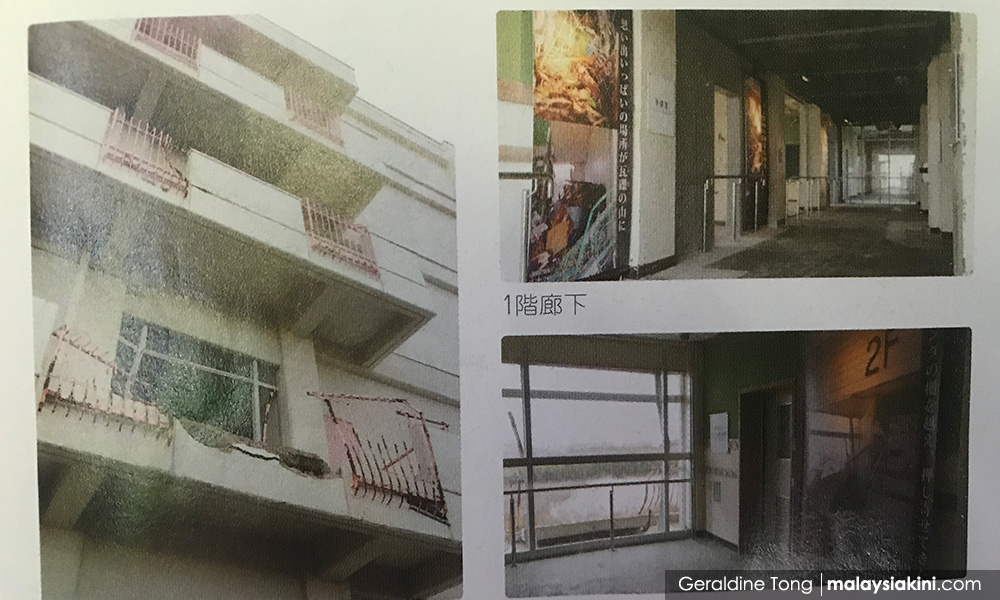

He had no idea at that time that the tsunami waves would reach up to the second floor of the school, with some of the debris crashing into the third floor as well.

The rest of the Arahama area was not so lucky. More than 190 lives were lost in Arahama on that day.

One Arahama resident who sought refuge at the school later described how he watched his town washed away by the “black waters” of the tsunami, calling it “hell”.

Even now, the Arahama area remains a lot emptier than it was before the March 11 earthquake and tsunami.

What is surprising is what the Japanese did well after the earthquake. The Arahama elementary school building is no longer used as a school, but the city has maintained it as a sort of memorial.

“It is our city’s goal to never again fall victim to a tsunami, to pass on the lessons we learned also and to show the real threat of a tsunami to future generations.

“For these reasons, the ruins of the Arahama elementary school building will be preserved, along with other records, and opened to the public,” says a brochure distributed at the elementary school.

While the instinctive reaction of most people after a natural disaster would be to rebuild and move on, this action by the city of Arahama shows that there might be merit in remembering the devastation caused by such disasters.

Instead of relegating such natural disasters to the past, Malaysia might do well to remember what is at stake when it comes to disaster risk reduction and that everyone needs to work harder to prevent such devastation from happening again.

It is also noteworthy that in scenes shown to us of the relief centres in Japan after the 2011 earthquake and tsunamis, the centres not only had the basics, they also had landlines and notice boards prepared for victims to contact their families and friends.

It appears to be a small gesture, but in such dire times, being able to stay connected could be an invaluable comfort to the victims, as well as their families and friends.

The media can also play a role in disaster risk mitigation and awareness, as shown in Japan as well.

It’s the responsibility of all

Shinichi Takeda was a journalist with the local Tohoku publication Kahoku Shimpo when the March 11 disaster happened.

Struck by the extent of the devastation and how unprepared they were for the earthquake and tsunami, Shinichi (photo) told a group of Malaysian journalists recently that he regretted that his publication did not do more to raise awareness about disaster risk reduction among the local populace.

This led to the formation of the disaster risk reduction and education project office in his publication, which he now heads. They organise workshops called Musubi-juku to share details of disasters and discuss a plan to reduce disaster risk.

While it should mainly be the government’s role to have programmes on disaster risk reduction, Shinichi said that as a local newspaper, they have a closer relationship to the residents and as such, can have more of an impact.

Not all media organisations can do the same thing as Kahoku Shimpo, especially with regard to the allocation they pour into this project, at four million yen (RM152,000) a year.

But it shows that the media does have its role to play in disaster risk reduction awareness and that those in the media cannot just sit around and wait for the government to take action.

Disaster risk reduction is the responsibility of all, and now would be a good time for Penang, as well as the rest of Malaysia, to start preparations to handle what seems to be an inevitability in the future.