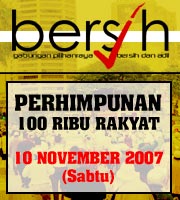

COMMENT | When it happened, the original Bersih rally of Nov 10, 2007 must have appeared to many people as if it had come out of nowhere. We had heard and read about it, of course. The organisers had announced the rally. The police prohibited it.

But was the post-Mahathir environment ripe for a mass demonstration? The Barisan Nasional’s electoral victory in April 2004 and Anwar Ibrahim’s release five months later, in September, seemed to have swept away the rebelliousness of Reformasi.

Towards the end of 2006, when opposition politicians considered organising a mass demonstration to demand electoral reform, the idea seemed odd. Why would a soundly thrashed opposition choose electoral reform to head its political agenda?

If there was logic to the oddity, it was the opposition parties’ calculation that they could revive their collaboration on the non-divisive ‘common denominator’ of electoral reform.

Hence, what became Bersih 2007 was spectacular, not so much for its unexpectedly large turnout and an unjustifiable police assault, as for having taken place at all.

Most people were caught off guard by Bersih 2007. Still, if the event was a proverbial bolt from the blue, it had struck amidst signs that the political milieu was far from lifeless. Three sets of conditions combined to make the Bersih moment an explosive one.

First, the Umno General Assembly in 2006, and again in 2007, saw shrill chauvinist outbursts from many delegates and the ‘keris-kissing’ antics of several leaders. Those displays, telecast live, and tolerated by Umno’s top leaders, revealed Umno’s callous mood and aggressive intents.

Yet from mid-2006 Umno’s smugness was shaken by a serious spat between Dr Mahathir Mohamad and Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. Accusations were followed by counter-accusations over Abdullah’s leadership flaws, Mahathir’s failings, and then PM’s son-in-law Khairy Jamaluddin’s influence over the administration.

Second, on Sept 26, 2007, two months before Bersih, the Bar Council had organised a ‘Walk for Justice’ by about 2,000 lawyers and NGO activists to protest against ‘Lingam-gate’. The scandal of judicial degradation compelled the regime to institute a royal commission of inquiry.

And two weeks after Bersih, Hindraf inspired an Indian uprising, a huge, unforeseen and angry expression of ethnic Indian grievances. The Bar Council-Bersih-Hindraf sequence, although no one had choreographed it that way, brought dissent from different directions to pose a multi-front defiance of the regime.

And two weeks after Bersih, Hindraf inspired an Indian uprising, a huge, unforeseen and angry expression of ethnic Indian grievances. The Bar Council-Bersih-Hindraf sequence, although no one had choreographed it that way, brought dissent from different directions to pose a multi-front defiance of the regime.

Finally, the opposition was looking to reinvent an alternative coalition to challenge BN for power. Anyone then could have cautioned the opposition politicians that their chance of success was remote. Unable to ‘hang together’, the opposition parties had ‘hanged separately’ and were routed by BN in 2004.

In short, just when the opposition parties seemed like they had nothing to lose, sudden shifts in the political terrain gave them a good deal to gain if they could find new ways of collaboration. Bersih became the starting point of their reinvention with a minimalist goal of fighting for electoral reforms ahead of the next general election.

Four demands were made of the Electoral Commission by Bersih, namely, the use of indelible ink, the clean-up of electoral rolls, the abolition of postal ballots, and fair access to the media for all candidates.

Four demands were made of the Electoral Commission by Bersih, namely, the use of indelible ink, the clean-up of electoral rolls, the abolition of postal ballots, and fair access to the media for all candidates.

For the opposition parties and civil society activists, Bersih’s four points constituted a minimal slate of demands to democratise the political system. It was common knowledge that unclean and unfair practices marred the conduct of elections. Bersih demanded that the Electoral Commission should stop ignoring, tolerating or abetting those practices.

Yet even opposition-minded voters might have resigned themselves to the ‘reality’ that the opposition could not obtain redress when its candidates legally challenged election outcomes with evidence of violations of existing laws.

Could the call for electoral reform seize the imagination of the general electorate then? Could Bersih attract a sufficiently large turnout for its principal organisers, the DAP, PAS and PKR? Without a successful rally, could the opposition parties revitalise their cooperation?

Formidable obstacles barred the path of the Bersih rally. The police issued its standard prohibition of an ‘illegal gathering’ and made threats of arrests. The controlled media warned of disruptions of trade and destruction of property. On the eve of the rally, the prime minister insisted that, “I will not be challenged”.

Formidable obstacles barred the path of the Bersih rally. The police issued its standard prohibition of an ‘illegal gathering’ and made threats of arrests. The controlled media warned of disruptions of trade and destruction of property. On the eve of the rally, the prime minister insisted that, “I will not be challenged”.

Such issuances of disapproval often had a dampening impact on planned gatherings. Society was so regularly assailed with reminders of ‘May 13’ that the populace was ordinarily fearful that mass demonstrations could descend into chaos.

Of course, there were large anti-regime protests in the time of Reformasi when protesters spontaneously rose out of visceral anger over Anwar’s ‘blacked eye’ maltreatment. No one in living memory, though, had organised a 100,000-strong rally, which was the Bersih organisers’ stated target.

A trinity of eruptions

On the appointed day, the rally started out from several locations in Kuala Lumpur and wound its way to Istana Negara. The organisers had planned for the rally to culminate there in the delivery of a petition for ‘Clean and Fair Elections’ to the king. But an orderly rally was forestalled when the police forcibly dispersed the marchers before they could reach the palace.

By then, however, Bersih 2007 had exerted the political impact that its organisers had hoped for. Perhaps not 100,000 people showed up but fair estimates put the attendance at between 30,000 and 40,000 participants.

As it were, Bersih 2007 had been timed to perfection. The rally proceeded on the very day after the Umno General Assembly was concluded. With over 90 percent of the participants being Malays, their presence expressed a predominantly Malay defiance of the regime that contrasted with the ‘non-Malay-bashing’ antics of the Umno General Assembly, telecast live to the nation.

Over the internet and via international media, coverage spread of opposition leaders jointly leading the Bersih rally, and collectively bearing the tear gas and water cannon assaults. As we would say today, the images of their working together again went viral.

Just in 2007 Bersih acquired a deeper political meaning that transcended its original four demands. Amidst deepening dissent, Bersih exposed a fresh crisis of the regime that was ignited by Umno’s insecurities, civil society’s indignation, and the opposition’s aspirations. The crisis created a historic space in which a narrowly framed pursuit of clean and fair elections could grow into an assault on Umno’s domination of society.

In the last quarter of 2007, Bersih’s impact would have been rather isolated and limited if Bersih had not formed a trinity of eruptions of social dissent with the Bar Council’s protest and the Hindraf demonstration. As a result, the last quarter of 2007 belonged with ‘the long 2008’ which would stretch all the way to cover the 12th General Election of March 2008, Anwar’s return to the Parliament after August 2008, and the ousting of Pakatan Rakyat in Perak in February 2009.

And out of the Pakatan’s defeat in 2009 emerged even stronger expressions of concern over electoral reform that would carry the momentum of Bersih into other demands for ‘Clean and Fair Elections’. No one in 2006 or 2007 planned a progression of four rallies. That came later, almost inevitably so in hindsight.

Part 2: Bersih 2.0 - resurrection at Stadium Merdeka

Part 3: Bersih 3 – the attempt to reclaim Kuala Lumpur

KHOO BOO TEIK is the author of ‘Beyond Mahathir: Malaysian Politics and its Discontents’ and, as reminded by P Ramakrishnan, a member of Aliran.