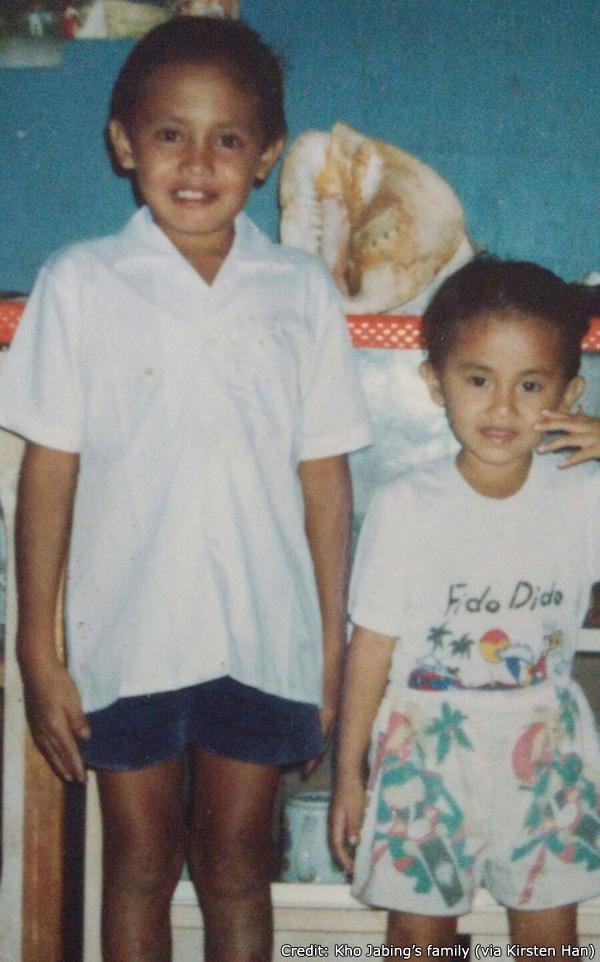

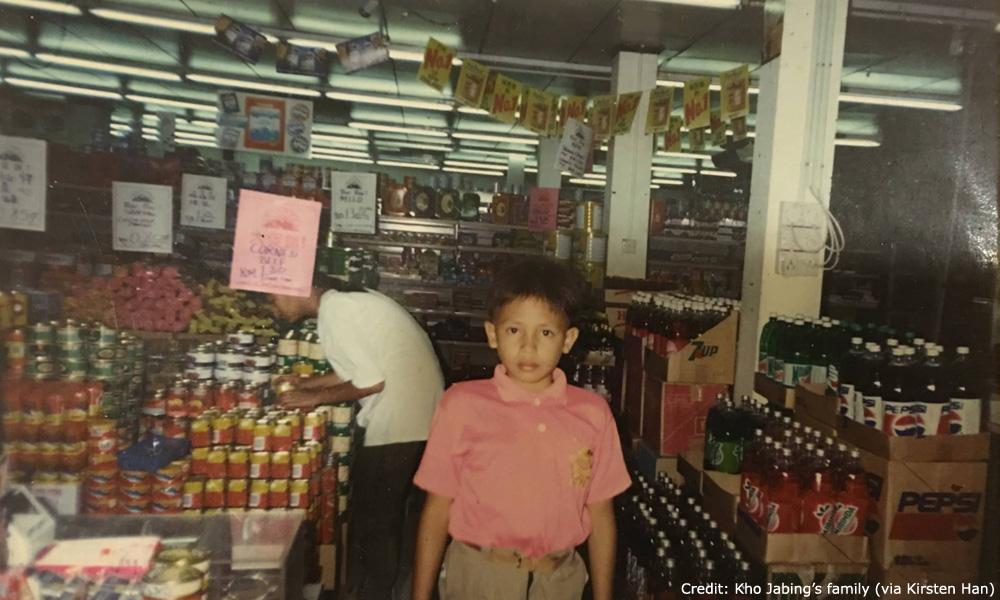

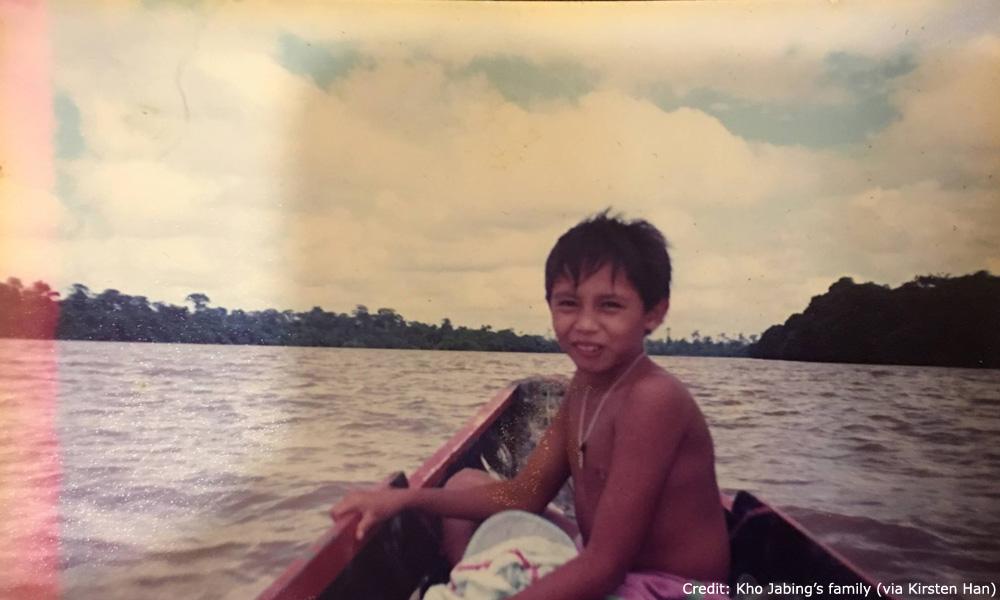

COMMENT This is Jabing Kho. He was born in 1984, in a taxi on the way to hospital.

He grew up in a longhouse and was very close to his little sister Jumai, who turns 28 years old today.

He worked on a family plantation, then as a technician laying cables in Miri before moving to Singapore to earn a better wage to help his family.

He called his mother twice a day - once when he woke up in the morning, and once before going to bed at night.

He got very drunk one night - we don't know how drunk exactly, or how much the excessive levels of Ethanol he had consumed affected his mental capacity, because this was never established properly in court.

He did a very stupid, awful thing. Even a High Court judge said his choice of weapon was impulsive.

He didn't mean to kill a man, but he did.

For this one moment of violence our Singaporean criminal justice system began to exact a slow, steady vengeance.

For this one moment of violence our Singaporean criminal justice system began to exact a slow, steady vengeance.

We sentenced him to death, then life, then death again.

He sat in prison for nine years knowing he was waiting to be taken to die.

The Cabinet decided on clemency, the president signed the warrant, the prisons scheduled the execution.

His family were told to buy clothes for his pre-execution photo shoot, and to make funeral preparations for a man who was, at that time, neither critically ill nor dead.

There is no death, no murder, more premeditated than what happened today.

Last night, as Jabing's legal team scrambled and struggled to prepare for their sudden 9am appeal hearing, Jumai told me that Jabing had wanted her to celebrate her birthday.

"Don't worry about me," he'd told her. "You should celebrate your birthday and not think about me. When you blow out the candles, you have to think that I am by your side."

I write this now because we are so often detached from and ignorant of the people the state kills in our name.

We think of them as soulless monsters, as "human trash" that needs to be thrown out.

We think of them as statistics in the Singapore Prison Service's annual reports.

Very often, we don't think of them at all. (It is likely that another man was executed this morning, but we don't even know his name).

But we need to see death row inmates for who they are: people who have made mistakes, people who have made bad decisions, people who might have been cruel, but also people who have families, who have struggles, who are full of contradictions like us.

They laugh, cry, joke, dream, hate and fear like any other person.

But unlike any other person, they will one day know, down to the minute, when they will die. And all they can do is wait.

Yesterday in court Jabing gave us activists a big wave. Then he bowed and smiled.

He was executed today, hours after the Court of Appeal dismissed his appeal for a stay of execution.

I'm sharing the photos his family has shared with me.

The government says it kills people like Jabing to keep us safe.

I don't know how Jabing's death has kept me safe; it's simply made me feel more hurt, more outraged and more fearful of a cold state machinery that knows no compassion, that would rush a man to his death out of procedural efficiency.

But if Jabing died in all our names, the least we could do is see these photos and know his face.

#RIP Kho Jabing. 1984 - 2016.

KIRSTEN HAN is a freelance journalist in Singapore and is a founding member of 'We Believe in Second Chances', a group campaigning for the abolition of the death penalty.