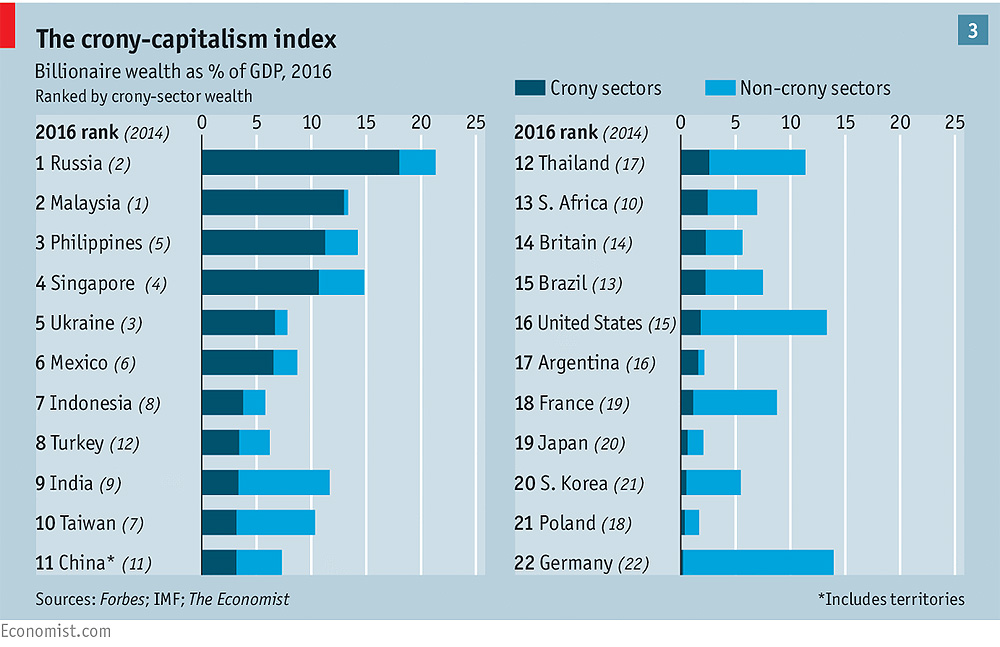

The Economist's second run of the index of crony capitalism saw Malaysia rising to number two, just behind Russia which clinched the crony capitalism crown.

Malaysia was number three in the index when it was first instituted two years ago in 2014, to test if the world was experiencing a global re-run of the late 19th century age of the American ‘robber barons’.

This, stated the business publication, is against the backdrop of the global fraud investigations into the state-owned investment arm, 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), that is answerable to prime minister Najib Abdul Razak

But The Economist said that despite the unearthing of crony capitalism by global probes, Malaysia continued to score badly on the index as cronyism has led to political instability.

Another interesting statistic to note is that if one were to look at the chart for the crony income and non-crony income in the countries listed, there is usually a substantial and noticeable gap between the two.

However, Malaysia's statistic showed almost all of the wealth in the country is crony wealth, with just a smidgen of difference between the two.

In any case, the index found that Russia scored the worst, "reflecting its corruption and dependence on natural resources. Both its crony wealth and GDP have fallen in dollar terms in the past two years, reflecting the Rouble’s collapse. Their ratio is not much changed since 2014."

Coming to shabby end

"Depressingly, the exercise suggested that since globalisation had taken off in the 1990s, there had been a surge in billionaire wealth in industries that often involve cosy relations with the government, such as casinos, oil, and construction. Over two decades, crony fortunes had leapt relative to global GDP and as a share of total billionaire wealth."

The publication, however, noted that its current run of the index seems to find that this new golden era of crony capitalism is coming to a shabby end.

It pointed to the probe into 1MDB, pony-tailed Indian tycoon Vijay Mallya fighting deportation back to India as the authorities there rake over his collapsed empire, and pressure on Brazil’s president, Dilma Rousseff, who is facing impeachment over alleged corruption.

The Economist also mentioned the campaign by Rodrigo Duterte, the front-runner to win the presidential election in the Philippines on May 9, to open up a feudal political system that has allowed cronyism to flourish.

While in China, bosses of private and state-owned firms are now routinely interrogated as part of President Xi Jinping’s (photo) purge of “tigers” (a purge that has left Mr Xi’s family well alone).

While in China, bosses of private and state-owned firms are now routinely interrogated as part of President Xi Jinping’s (photo) purge of “tigers” (a purge that has left Mr Xi’s family well alone).

Worldwide, tycoons’ offshore financial cartwheels have been revealed through the Panama papers.

"The economic climate has been tough on cronies, too. Commodity prices have tanked, cutting the value of mines, steel mills, and oilfield concessions. Emerging-market currencies and shares have fallen. Asia’s long property boom has sputtered," said the publication.

The result, it said, is a steady shrinking of crony billionaire wealth to $1.75 trillion, a fall of 16 percent since 2014.

Long road to reform

In richer countries, the index found that crony wealth remains steady, at about 1.5 percent of GDP, while in the emerging world it has fallen to four percent of the GDP, from a peak of seven percent in 2008, with wealth shifting away from crony industries and towards cleaner sectors, such as consumer goods.

"Despite this slowdown, it is too soon to say that the era of cronyism is over - and not just because America could elect as president a billionaire whose dealings in Atlantic City’s casinos and Manhattan’s property jungle earn him the 104th spot on our individual crony ranking."

However, The Economist stated that there is still good reason to worry about cronyism since some countries, such as Russia, are going backwards, and if global growth ever picks up, the commodities sector will recover, along with the rents that cronies can extract from them.

It noted that even in countries that are cleaning up their systems, or where popular pressure for a clean-up is strong, reform is hard. And many political parties still rely on illicit funding, while courts have huge backlogs that take years to clear and state-run banks are stuck in time-warps.

And across the emerging world, the response to lower growth is likely to be more privatisations, which in the 1990s is a key source of crony wealth then, and may be so yet once again.