ANTIDOTE “This is the Abang river, it has been muddy since October 2015. The people of Ba Abang cannot drink the water from this river. These are the problems we Penan face.

“The companies working here are Interhill and GT - both companies are (logging) here,” said Tua Kampung Panai Irang, chief of Ba Abang, a remote village in Baram, eastern Sarawak.

"We put up blockades, but the company bulldozes the blockades. We make reports to the Forestry (Department) and to the police, but they support the companies.”

"We put up blockades, but the company bulldozes the blockades. We make reports to the Forestry (Department) and to the police, but they support the companies.”

The rural communities of Baram, including Penan, Kenyah and Kayan, have been fighting desperately on two fronts.

The first is the Baram Hydroelectric Dam, a ‘mega-project’ that threatens to drown some 400 square kilometres (roughly the same area as Kuching), and to displace 20,000 villagers.

The other battlefront is defending the villagers’ native customary rights (NCR) land, forests and water catchment areas around their homes, from deforestation and pollution by logging giants like Interhill, and its subcontractor GT.

The other battlefront is defending the villagers’ native customary rights (NCR) land, forests and water catchment areas around their homes, from deforestation and pollution by logging giants like Interhill, and its subcontractor GT.

On both issues, Sarawak Chief Minister Adenan Satem has made election promises.

Adenan promised he would crack down hard on illegal logging and protect NCR land. Despite his stirring speeches, no convictions for illegal logging have been forthcoming, and logging has continued at the same frantic pace in Baram and elsewhere in Sarawak’s NCR forests.

Adenan has not touched the ‘legal’ timber concessions issued by his predecessor and former brother-in-law, Abdul Taib Mahmud.

Adenan has not touched the ‘legal’ timber concessions issued by his predecessor and former brother-in-law, Abdul Taib Mahmud.

Adenan has pushed for timber tycoons like Hii King Chiong, Janet Lau and Tiong Thai King to be elected as state assembly representatives. Adenan has promised “my Chinese candidates” would be appointed to his cabinet.

Temporary Baram dam victory

The villagers have won, for the time being, on one front - the Baram dam has been shelved.

Taib and Adenan have been confronted with obstinate protests, and blockades at Long Lama and Long Naah, lasting 18 months, across the dam access roads.

Adenan was forced to make a U-turn, conveniently in time for the ongoing state elections campaign. Adenan remained adamant he was his own man, and had not backed down in the face of protesters.

“The others put it to their credit... (they said) they agitate for it, I am forced to withdraw the project - no! That is not the reason. The reason is that I have examined the matter. There’s no need to have another big dam,” Adenan announced on May 3.

“We can have mini-dams and so on, but not a big dam, especially when we don’t supply (power) to west Malaysia any more.”

Anti-dam campaigners point out that the Bakun Dam had been shelved twice as well, but was eventually completed in 2011, at the cost of immense human suffering among the resettled communities.

Local Kenyah, Penan and other Orang Ulu villages were destroyed in Bakun. Some 10,000 people were transplanted to ramshackle new longhouses, with inadequate farming land and miserable incomes.

Taib had also claimed, at various times in the past, that the Bakun dam was unnecessary, especially because underwater power transmission to peninsular Malaysia was not feasible.

Yet Taib went ahead with the resettlement of Bakun villagers, the logging of their abandoned NCR land, and construction of the dam.

Adenan has now parroted the same assurances regarding Baram.

Cahya Mata Sarawak (CMS), a construction and transportation conglomerate owned by Taib’s family, stands to earn billions of ringgit from the construction of 12 ‘mega-dams’ throughout Sarawak, including Bakun, Murum, Baleh and Baram - part of Taib’s ‘SCORE’ energy scheme.

Pollution from illegal logging

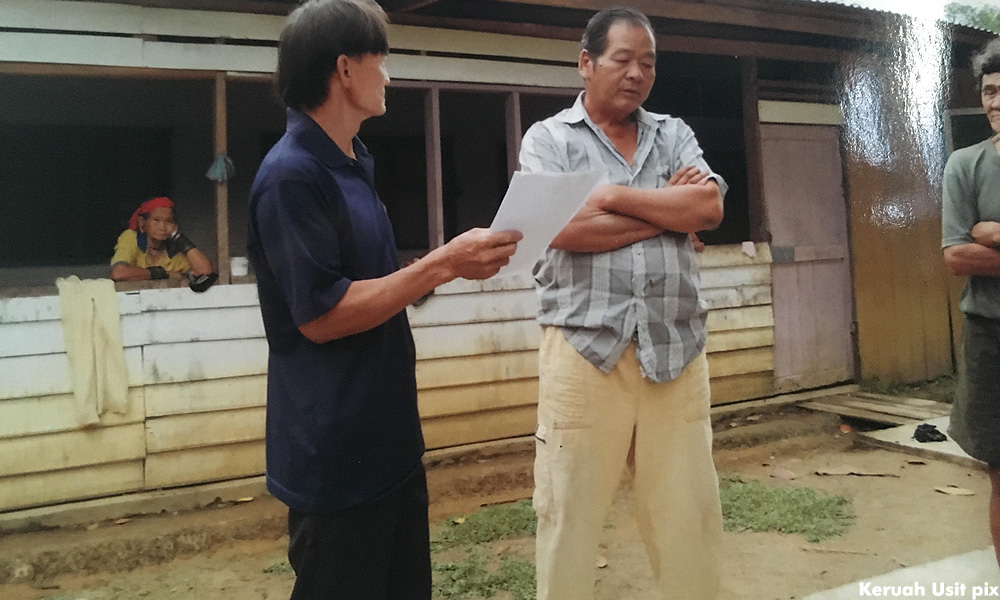

Tua Kampung Panai told Malaysiakini that pollution from illegal logging has been worsening, despite repeated warnings from the villagers to the loggers and authorities.

“Diesel was leaking like a black stream into the river from the bulldozers, and from the fuel tankers brought in by the companies,” he said.

Panai said the Penan know certain trees are poisonous to humans and fish, and these were among the fallen trees and logs that were bulldozed into the river.

Panai said the Penan know certain trees are poisonous to humans and fish, and these were among the fallen trees and logs that were bulldozed into the river.

“My grandson’s skin became itchy after bathing in the river. Our water supply from the (gravity-feed) pipe dries up if there is no rain for a few days, and we cannot use the river water.”

The bulldozers were not only working on the banks of rivers and streams, causing soil erosion and water pollution, Panai said, they were even driving into the water to cross streams.

The villagers have been erecting simple blockades of branches across the logging access roads, to stop the bulldozers, since 2014.

“Interhill has been ordering their workers to destroy our blockades,” Panai said.

“When we protested to the mandur (manager) Ling, he told us they would keep working, no matter what we say or do.”

“When we protested to the mandur (manager) Ling, he told us they would keep working, no matter what we say or do.”

The slogan of ‘Sarawak for Sarawakians’ continues to ring hollow for these rural communities. Land and forests have fallen under the control of the state throughout the 53 years of Sarawak’s elected governments.

Yet these rural communities have never given up, and continue to defend their NCR land and rivers - election after election.

KERUAH USIT is a human rights activist - ‘anak Sarawak, Bangsa Malaysia’.