When the Nepal Embassy in Kuala Lumpur made the shocking revelation last year that nine of its migrant workers were dying every week in Malaysia, it surprised everyone, except perhaps the workers themselves.

For them, dying on the job in Malaysia has become a part of life.

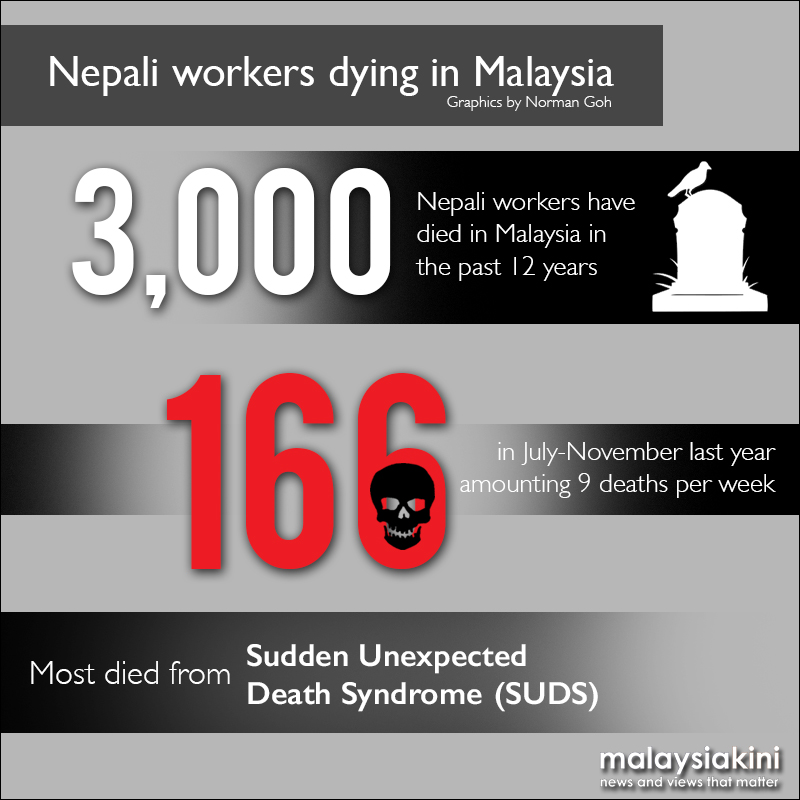

Embassy records show that nearly 3,000 Nepali workers have died in Malaysia in the past 12 years, 166 of them in the five months between July and November last year alone.

For that period, nine Nepali migrant workers on average died every week in Malaysia, according to the embassy.

Most of them died from what health experts call Sudden Unexpected Death Syndrome (SUDS).

“Just a few months back, another fellow Nepali worker simply dropped dead while walking to work,” said Dilip Malla, 43, who is employed as a security guard in Damansara. “We later learned it was a heart attack. It was so sudden.”

Doctors and labour activists are puzzled at the abnormally high mortality rate from SUDS among Nepali overseas contract workers not just in Malaysia but also in Qatar, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and other Gulf countries.

Although research is sparse and autopsies are rarely performed on dead migrants, the high fatality rate is attributed to overwork in hot and humid conditions, excessively air-conditioned living quarters, worry about family back home, as well as stress from exploitation and low pay.

Reduced earnings due to falling ringgit

In Malaysia, an additional anxiety is reduced earnings due to the falling ringgit, which has continued to plunge as the net petroleum exporter grapples with low oil prices.

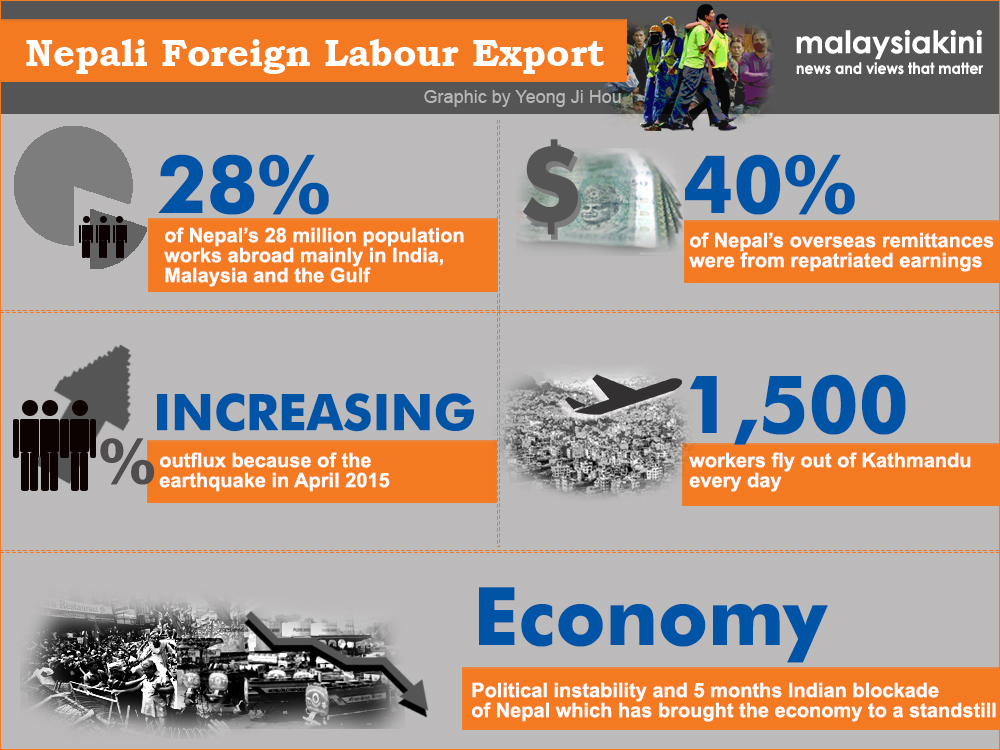

Nearly 20 percent of Nepal’s 28 million population works abroad: mainly in India, Malaysia, and the Gulf, and remittances from workers abroad makes up a quarter of the country’s GDP.

With 700,000 employed in plantations and factories, Malaysia has the highest number of Nepali migrant workers and the earnings they send home makes up 40 percent of Nepal’s total overseas remittances.

But the country also registers a disproportionate number of deaths of Nepalis.

About 1,500 workers fly out of Kathmandu every day, and this number is increasing because of the earthquake in April 2015, as political instability and the five-month Indian blockade of Nepal brought the local economy to a standstill.

Aegile Fernandez, programme director at Tenaganita which defends rights of migrant workers in Malaysia, says death of foreign workers are often overlooked despite the shocking figures.

“We see high suicide rate and several cases of sudden death. The government should be more transparent and in-depth research should be carried out. Unless that is done, we won’t know why they are dying," she said.

A government hospital doctor who treats migrant workers, who asked not to be named, said most sudden deaths are a result of cardiac arrest.

“However I can’t say for certain what is causing the sudden deaths. We never carried out any detailed investigation," she said.

Though she added that the influx of migrant workers has brought diseases like tuberculosis (TB) and malaria, which are rare in Malaysia.

Though she added that the influx of migrant workers has brought diseases like tuberculosis (TB) and malaria, which are rare in Malaysia.

Last year, the Malaysian government decided to withdraw subsidies to non-citizens for medical fees, and increased medical fees for non-nationals by 30 percent. The Health Ministry also puts a limit on prescription drugs for foreigners.

Public health experts however argue that this actually adds health risks to Malaysians, even if it does save the government some extra expenditures.

Besides infections, migrant workers are also not aware of the precautions they need to take in the extreme climate conditions, which differ from temperate Nepal.

Working conditions in plantations and factories are often harsh, with the dangers of dehydration and inadequate nutrition.

“The Nepalis might not be used to such long hours of work, under scorching heat but they aren’t also given proper health care and training beforehand,” added Aegile.

Work up to 18 hours a day

Shamser Nepali who runs clinics in Kathmandu that provide health check-ups to migrant workers said: "In Malaysia, migrant labourers work up to 18 hours a day and drink cheap spurious alcohol before they sleep and they die in their sleep."

Last January, a riot broke out at a plywood factory in Kedah when Nepali workers protested the death of a colleague who had difficulty breathing and died because he wasn’t taken to hospital in time.

Protesting workers were arrested and five deported. A month earlier, two Nepalis in the same factory had also died of SUDS.

In another case, more than 1,000 Nepali workers protested at the factory in Johor when a fellow worker died due to lack of health care last August. Some 50 workers were arrested and most of them sent back to Nepal.

"The rate at which Nepali workers are dying abroad is alarming because they are too young to die," says Ganesh Gurung, Nepal's foremost expert on migration and remittance economy.

"Our mortality rate could be high because of deaths of new-borns, children, the elderly, and chronically-ill patients. But if young and healthly people die at this rate, we must find out why it is happening," he said.

Figures show that most of the deaths of Nepali overseas contract workers occur in Malaysia.

Between July 2014 and July 2015, a total of 1,002 Nepali workers died, with 425 Nepali in Malaysia. Second was Saudi Arabia and third, Qatar, according to figures from the Foreign Employment Promotion Board in Kathmandu.

Qatar, which has 550,000 workers from Nepal, had only 178 deaths but more than half of them due to "sudden heart attacks".

The Qatari authorities have said that this corresponds to the national average for heart attack deaths in Nepal, but public health experts argue that the fatality rate is disproportionate because they involve healthy young males and is nearly 10 times higher than the death rate from heart attacks for that demographic back in Nepal.

In any case, as Malaysia continue to play host to thousands of job-seeking Nepali, something may need to be done so that the country only contributes to the earnings remittance, and not to an ever increasing death rate.

Part 2: Many migrant Nepalis find only pain in Malaysia

SONIA AWALE, an intern with Malaysiakini , hails from Nepal and is pursuing her Master's in Journalism at the University of Hong Kong.