Holding a hand rail as the LRT sways, a tudung-clad young woman, just out of her teens, barely looks up. She is enraptured as she takes her hands off the rail and turns the page. The train stops, and for a moment the spell is broken.

‘ Alamak ’, she thinks, realising she just missed her stop. She rushes out, her finger still marking the page of the book – ‘Murtad’ (Apostate) - and makes her way to the other side of the platform to retrace her steps, her mind still filled with words.

Welcome to the golden age of Malay independent publishing.

Once a rare sight in the capital city of Kuala Lumpur, one is now hard-pressed not to notice youths holding books, with titillating covers and titles which seem to push the envelope.

Holding the key is what many would perceive to be the Malay indie publishing mafia – Amir Muhammad (Buku Fixi), Mutalib Uthman (DuBook Press), Aisamuddin Md Asri (Lejen Press) and relative newcomer Zul Fikri Zamir (Thukul Cetak).

Over the past five years, they have published hundreds of titles - mostly by young first-time writers - sparking a sort of renaissance in both the publishing scene and Malay readership.

What is behind the growth of this scene? And more importantly, why did these young men (all are under 35, except for Amir who is 43) decide to become publishers, in a country where the average person reads seven pages a year?

DuBook Press CEO Mutalib

(photo)

said he took the plunge because the official publisher and the main driver for Malay publishing – Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) – is “

tak berguna

(useless)”.

DuBook Press CEO Mutalib

(photo)

said he took the plunge because the official publisher and the main driver for Malay publishing – Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) – is “

tak berguna

(useless)”.

“They don’t publish interesting books. Their (office) building is big, but their brains are small.”

DuBook is a play on the Malay word for hyena, ‘dubuk’, and the publishing house literally preys on what cynics would say is the carcass of DBP. One day, Mutalib said, he wants to “buy off DBP”.

“We have to thank DBP for creating such bad conditions that indie (publishers) had to take over. We are not sure what exactly it is that they have been doing, but thank you. It is because of DBP that we can survive and further flourish the alternative scene,” Thukul’s Zul Fikri said, agreeing.

'Books fail if no one reads them'

The disdain appears to be mutual.

DBP views the Malay publishers poorly, and believes the works they publish as unworthy of being called literature.

Indeed they are not. Most of the work published by the independent houses would fall under the pulp fiction category.

The language used is a hodgepodge familiar to youths who speak it every day, and the story lines are nothing highbrow. But so what?

“No matter how high the standard of the language is, if the particular book fails to get people to read it, then the book has failed,” Lejen Press’ Aisamuddin says, brushing DBP’s criticism off the matter-of-factly.

Founded in 2011, Lejen Press has a team of 11 who go through manuscripts and, ironically make sure the books adhere to a standard of grammar.

“We only use

bahasa pasar

(street lingo) in dialogues because that is how people speak, anyway.”

“We only use

bahasa pasar

(street lingo) in dialogues because that is how people speak, anyway.”

Lejen was founded several months after Buku Fixi – the (young and hip) grandfather of Malay indie publishing. Its founder Amir (photo) , had prior to that made a name for himself in film-making.

His two latest films ‘The Last Communist’ (2006) and ‘Apa Khabar Orang Kampung’ (2007) were banned, and for a while people looked to the soft-spoken Amir as the next big thing in Malaysian cinema.

But the wunderkind was frustrated. He just couldn’t find books he wanted to read in the local scene.

Typically, he started publishing them himself.

He had between films edited and curated anthologies for local publisher Silverfish, but Silverfish published in English and catered mostly to the urban, English-speaking middle class.

Amir believes that like him, the growing (Malay) middle class in Malaysia who can afford books are craving for a bit more variety. And thanks to these indie publishers, more and more youths are reading book - or at least buying them to keep up with the Joneses.

Looking cool

Lejen's Aisamuddin is not bashful about the fact that many youths buy Lejen books so they can hold them in public and look cool.

“But we have to think about why youngsters, especially males, were embarrassed to bring books with them wherever they go.

“It was a stigma in our society if you go around holding books with girlish covers and flowery titles.

“A different kind of touch was needed to create a sense of ownership. Now people are not embarrassed to show that they read books,” said Aisamuddin (photo) , who holds a degree in electronics.

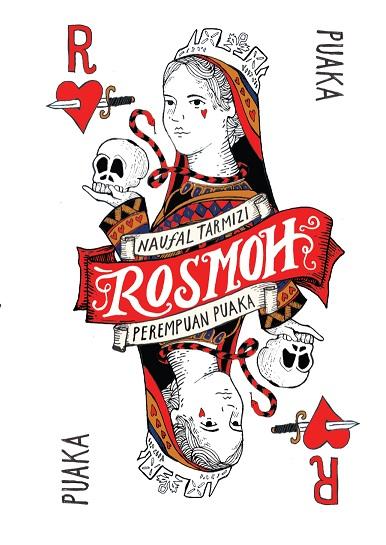

Lejen’s books are definitely eye-catching, to say the least. Among controversial titles include ‘Rosmoh: Perempuan Puaka’ (‘Rosmoh: Devil Woman’) and ‘Babi: Bercinta di Balik Api’ (‘Pig: Love Behind Flames’)

Lejen’s books are definitely eye-catching, to say the least. Among controversial titles include ‘Rosmoh: Perempuan Puaka’ (‘Rosmoh: Devil Woman’) and ‘Babi: Bercinta di Balik Api’ (‘Pig: Love Behind Flames’)

“ Babi (pigs) is taboo in the Malay community, it is seen as something dirty. But we are confident that no one can deny the use of the word babi for the title of the book.”

Recently, a politician slammed the publisher as “rude” for choosing such a title but nothing fazes Aisamuddin very much.

His team did not go out of their way to stir the pot with the Rosmoh title, he said, despite the title character sharing the same name as the prime minister’s wife.

Rosmah, he said, is the main character’s name, and the book is about shamans (

bomoh

). So it’s only natural that the title be ‘Rosmoh’.

Rosmah, he said, is the main character’s name, and the book is about shamans (

bomoh

). So it’s only natural that the title be ‘Rosmoh’.

“We told him that Rosmah could be anyone’s name. And the title is not even Rosmah but Rosmoh,” he said.

“There a thousands of books in a bookstore. Aren’t we attracted to eye-catching covers and titles?” he rationalised.

Fixi’s titles are easily recognisable in a crowded bookstore. They usually have bold cover art in striking colours and carry their one-word titles with aplomb.

Pop and Plato

It is enough to pique the interest of their readers, who are mostly Malay and in their late teens or early 20s. About a quarter of their readers are male – “quite high for local fiction”, he said.

The word ‘Fixi’ is also a play on words. Fixi is urban parlance for fixed-gear bicycles popular among youths, but it is a play on the word fiksyen . It reads like a cheeky prod on DBP’s adoption of English words into the Malay language. (Think audien , for audience, despite the existence of the word penonton to mean the same).

Lejen, too, is a bastardisation of the English word ‘legend’, and readers proudly display their allegiance to the publisher through stickers which read ‘I am Lejen’. Most of Lejen's readers are also female, aged 20 to 30.

This is where Thukul, the new kid on the block, bucks the trend. Founded last November, the publisher boasts a 60:40 male to female ratio. And unlike the other publishers, Thukul steers away from pulp fiction.

This is where Thukul, the new kid on the block, bucks the trend. Founded last November, the publisher boasts a 60:40 male to female ratio. And unlike the other publishers, Thukul steers away from pulp fiction.

“Our idea is to inject serious discourse in the indie genre,” Zul Fikri (photo) said.

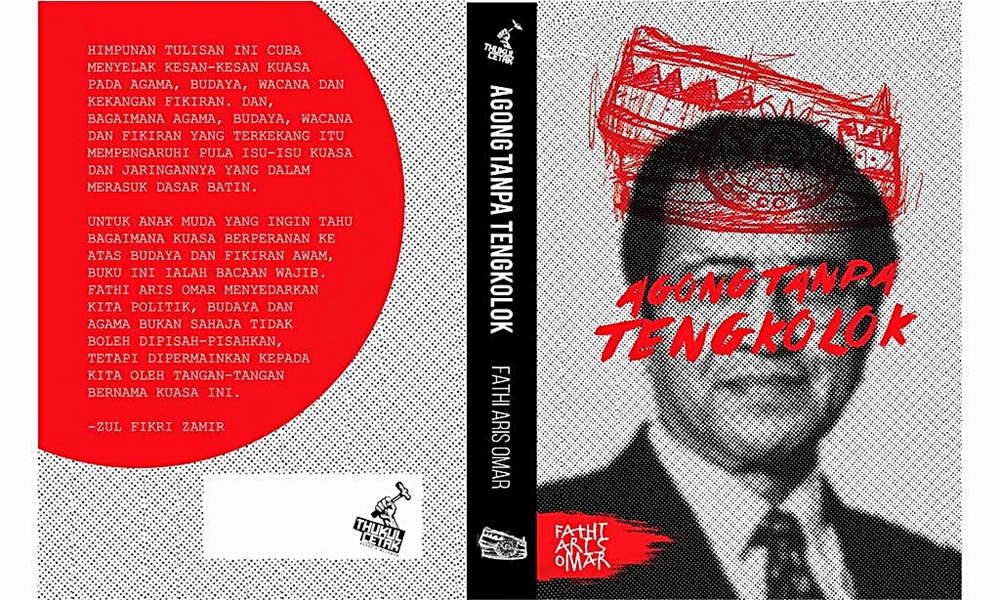

The first book Thukul published was a serious of political commentaries by former Malaysiakini chief editor Fathi Aris Omar’s book, Agong Tanpa Tengkolok.

The pop art cover belies the heavy subject matter, but the readers, mostly under 25, are lapping it up. The book is now in its third print and Thukul has raised enough funds to leap from a virtual store to have a brick and mortar presence like Lejen and Fixi.

Zul Fikri, a 30-year-old former schoolteacher, said his company plans to translate Greek philosopher Plato’s works and the works of Czech writer Franz Kafka.

“We have to ‘pop’ them, turn them into something hip. This is so that youngsters don’t only feel hip when they read Buku Fixi and Dubook Press books only.

“They must also feel hip reading about philosophy and the economy,” he said, explaining that Plato’s book will be adapted and presented in simple language.

Escaping censors and jealous oldies

Zul Fikri somewhat represents the second wave of Malay indie publishing. The occasional writer has four books published – the first, by DuBook in 2012.

He says Thukul’s book store will be more than a book store. It will also be a library consisting of “rare” books, and will also have a mini bar for students to spend their time.

“We have conducted a talk and we have also held a film viewing. Next February we plan to have a theatre show as well as a writing workshop,” he said.

One title by Lejen has been banned by the Home Ministry, while another of Thukul’s title has been blocked from entering East Malaysia.

One title by Lejen has been banned by the Home Ministry, while another of Thukul’s title has been blocked from entering East Malaysia.

Copies of Thukul’s Agong Tanpa Tengkolok were prevented from entering Sabah suspected to be because its cover featured former premier Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s face (photo) .

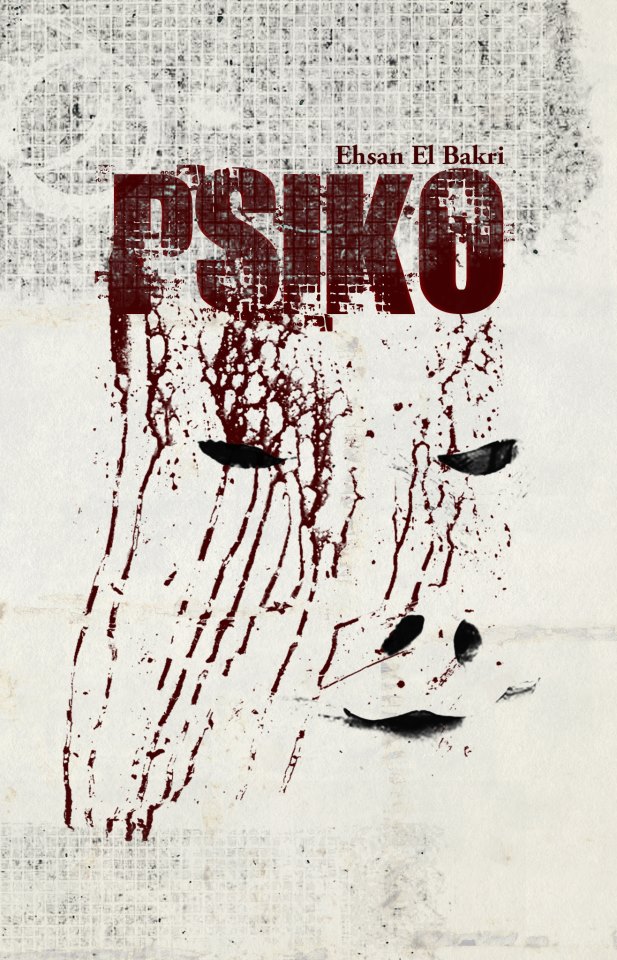

Lejen Press’ Psiko was banned by the Home Ministry due to its violent and sexual content.

“There are rumours that two of our books Aku__, Maka Aku Ada and Nazi Goreng will be banned. We are just waiting for the letter,” DuBook’s Mutalib said.

Fixi’s books have escaped censors, but not the wrath of “jealous writers” from older publishers who apparently tried to incite a boycott, Amir said.

Fixi’s books have escaped censors, but not the wrath of “jealous writers” from older publishers who apparently tried to incite a boycott, Amir said.

“One even said we should be emulating safe material like Harry Potter ; the poor dear probably didn't realise that many conservative

Christians in Western countries have tried to get Harry Potter books banned from libraries.

“There are prudes and puritans everywhere,” Amir said.

Even so, Fixi last month started labeling their books with ‘Untuk Pembaca Matang' (for mature readers) as an advisory.

By and large, however, the devil may care attitude runs deep among the tight-knit Malay indie publishing mafia.

“We enjoy each other's company and our WhatsApp group has more contentious material than that of any political party,” Amir quipped.

Sharing is caring

There is strong camaraderie among the publishers despite the fact that they are competing in a fairly small market. Lejen's Aisamuddin calls it a “friendly rivalry”.

“This is the reason why we look orderly. We become orderly because we support each other,” Zul Fikri agreed.

And the mafia can be friends with everyone, Mutalib said, “except for DBP and (Karangkraf’s) Buku Pojok”. Karangkraf is Malaysia’s largest magazine, newspaper and book publisher – naturally too big to run with the indie cool kids.

The close ties are also good for business, Aisamuddin said. When someone reads a book by Fixi, they’d likely to also pick up a book from Lejen or DuBook or even Thukul.

The close ties are also good for business, Aisamuddin said. When someone reads a book by Fixi, they’d likely to also pick up a book from Lejen or DuBook or even Thukul.

“When there is healthy competition, the future of the book industry looks more appealing,” he said.

Sharing is caring, and for Amir, this includes giving content out for free.

“Like Wattpad (online writing community); we are on it and provide entire novels for free.

“Because I believe in what the founder of Smashwords (ebook distribution platform) said: ‘The greatest danger you face as a writer isn't piracy but obscurity’.”

MALAYSIANS KINI is a series on Malaysians you should know.

Previously featured:

Subversive book club thrives in Shah Alam and beyond

Meet Syed Saddiq, your freedom of speech crusader

‘It’s not punk rock, it’s punk ideology’

Paramedic goes ‘white to black’ to lead medic team at Bersih 4

Siti Aishah – from blogger to youngest senator

A lawyer hooked on ‘the perfect murder’

DAP ideology suits rapper Edry just fine

A PKR Youth leader and a reluctant politician