Author Janet Steele, who spent weeks in Malaysiakini office in Bangsar Utama last year, finds out what makes journalists in this online daily tick. This is her fourth of a five-part series.

Every day, Malaysiakini posts about 25 stories to its website, most of which are written between 4pm and 7pm. ( Malaysiakini's research has determined that most people read the website when they first get to work in the morning, during lunch, and late at night.)

These stories are determined at two meetings: the 11:30am editors' meeting, and the 6pm general staff meeting. Both meetings last about 10 to 15 minutes.

These stories are determined at two meetings: the 11:30am editors' meeting, and the 6pm general staff meeting. Both meetings last about 10 to 15 minutes.

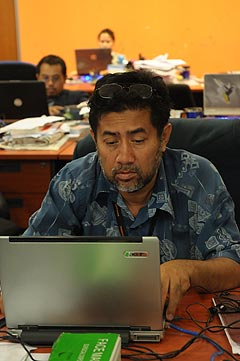

The 6pm meeting is led by chief editor K Kabilan ( left ), a former language teacher who used to work at the New Straits Times . Everyone in the newsroom participates.

The meeting is relaxed and free-flowing - Chinese editor Yong Kai Ping describes the atmosphere as "egalitarian" - and the main focus is to discuss story ideas for the following day.

The editors' meeting takes place at 11:30am, with the unusual feature that most of the editors remain standing around the small glass-topped table.

Gan explains that in the very beginning, they had one-to-two-hour meetings starting at 10 in the morning, but that by noon they were still meeting, and nobody had done any work. So about three years ago, they switched to a five-minute briefing format, and everybody stands up.

Aside from the format, one of the most surprising things about the editors' meeting is the degree of unanimity among the seven editors who attend. The point of the meeting is to give out assignments, see if there have been any new developments since the previous night, and follow up on stories that are in the mainstream press. The discussion is always brief but frank. People talk openly with one another, and are unafraid to say what they really think.

Nash Rahman ( right ), the Bahasa Malaysia section editor, says that he views his role as being able to say things like "if you do it this way, you will offend people. But there are so many ways of doing it."

Nash Rahman ( right ), the Bahasa Malaysia section editor, says that he views his role as being able to say things like "if you do it this way, you will offend people. But there are so many ways of doing it."

He often speaks to Gan as a friend, and will say "as a Muslim, we don't like this," or "this is how the Malays will look at it."

Nash adds that in other media there is so much self-censorship that there wouldn't even be any point in having such a discussion.

If there is a modal Malaysiakini story, it is one that involves freedom of expression, civil liberties and human rights. There is a remarkable sense of shared news judgement.

When I asked veteran journalist P Padmaja how she would describe the typical Malaysiakini story, she said " Malaysiakini asks basic questions: Is something wrong? Can we raise a debate on this?" She noted that Malaysiakini looks for stories that the other media won't go after, adding that " Malaysiakini should speak for people who cannot speak for themselves."

Because Malaysiakini's editorial staff is so small, it does very few original investigative reports. Much of the reporting in Malaysiakini is what Silvio Waisbord has called "watchdog journalism", and originates with leaks or tips from sources - often from within the government.

There are a number of reasons for this lack of original investigations, including a legal system that does not protect journalists, and also fear of defamation proceedings. Malaysiakini journalists tend to think of investigations in terms of government corruption.

There are a number of reasons for this lack of original investigations, including a legal system that does not protect journalists, and also fear of defamation proceedings. Malaysiakini journalists tend to think of investigations in terms of government corruption.

A typical example would be a story that Malaysiakini did less than one week before the election, when senior journalist Beh Lih Yi was leaked a letter that had been written by the then Penang chief minister to Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi.

The letter asked that the federal government offer a RM1 billion "project" to the Motorola corporation, enticing them to stay in the state. Opponents of the government characterised this project as a bribe. The Chief Minister's office ultimately confirmed having sent the letter, although they denied that a bribe was involved.

The story was a scoop for Malaysiakini , but the fact that it benefited Anwar Ibrahim's opposition party PKR (which had been hinting of the existence of the letter for some time) raises a difficult question: how do Malaysiakini journalists reconcile what many characterise as their "activism" with their reputation as an independent news organisation?

Gan concedes that this can be a problem. "We have to convince people that we are not the opposition," he says.

"This can be difficult to do. Even some Malaysiakini staff are critical of what they see as having given too much space to Anwar's PKR during the 2008 election, although they are quick to add that some of this coverage stemmed from Anwar's skillful use of media.

"This can be difficult to do. Even some Malaysiakini staff are critical of what they see as having given too much space to Anwar's PKR during the 2008 election, although they are quick to add that some of this coverage stemmed from Anwar's skillful use of media.

"Others point out that Malaysiakini actually focused more on Anwar himself than on the PKR party as a whole, citing complaints that other party candidates were not getting sufficient coverage."

There is no question that Malaysiakini journalists see themselves as agents of change. When I told Gan about a recent survey of attitudes of journalists in the Arab world, and the authors' two functional categories of "guardians of tradition" versus "change agents", he laughed and said "you know how we would all answer."

For Malaysiakini journalists, it is obvious that change is the goal. Padmaja, for example, says she measures how good a story is by whether or not it leads to change. A no-nonsense person who is also the editor most responsible for training new journalists, she concludes " Malaysiakini training gives you the tools to challenge the status quo."

One of the most important tools that Malaysiakini journalists use is empirical evidence - "the facts". Malaysiakini will often back up its stories by posting original documents in their entirety. Padmaja says she frequently asks young reporters "what is your proof?"

Videos make impact

But the most interesting use of documentary evidence is the use of video on Malaysiakini.tv.

Shufiyan Shukur ( left ) is the senior producer of Malaysiakini.tv, the video section of the website.

Shufiyan Shukur ( left ) is the senior producer of Malaysiakini.tv, the video section of the website.

A large, friendly man with a ready laugh and a tendency not to take himself too seriously, he has been involved with Malaysiakini since 2005. He has been in the travel business, and before that worked for Gan at the Special Issues section of The Sun .

Growing up in Johor and the UK, he describes himself as "a mainstream Malaysian". According to Shufiyan, videos became important at Malaysiakini after 2006, when documentary producer Indrani Kopal was hired under a grant to provide Tamil language news coverage.

After deciding that the Tamil community would be better served by video than text, they created Malaysiakini.tv. Shufiyan describes the philosophy behind the videos in this way: "the orders are just shoot the video, we don't care what it sounds like, we don't care how it looks, whether it's shaky, whether it's blurry, whether its audio stinks - it doesn't matter, just bring in the visuals."

Malaysiakini's videos are both testimony and eye-witness accounts. As Shufiyan makes clear, "they are not TV in how we know TV to be - because it is not a show."

Malaysiakini's videos are both testimony and eye-witness accounts. As Shufiyan makes clear, "they are not TV in how we know TV to be - because it is not a show."

He explains, "I come from a non-broadcasting background, so I look at videos very differently. There are probably producers, people from television who would just cringe. You don't produce it this way? Who says you don't? I think that this is how we made a difference."

Some of Malaysiakini.tv's most influential videos have been of the destruction of Indian temples and immigrant squatter communities. Shufiyan describes the story of the demolition of Kampung Berembang, when authorities from the Religious Department came with bulldozers to destroy a surau, or Muslim community prayer house. Because the villagers' houses had already been demolished, they placed their children in the surau .

Shufiyan explains that when the authorities came, they said that "there was nothing they could do because this so-called surau is in a place that is not gazetted [registered] as a place of worship. It's an illegal structure."

"I was there. I was the only cameraman. They stopped all the press but I sneaked inside. There were arguments going on outside, and then there was a scuffle between one of the villagers and the contractors. And you should have seen the fear on those children's faces. They were screaming, they were crying.

"I was there. I was the only cameraman. They stopped all the press but I sneaked inside. There were arguments going on outside, and then there was a scuffle between one of the villagers and the contractors. And you should have seen the fear on those children's faces. They were screaming, they were crying.

"And I got a lot of that on tape. [These are the] kinds of scenes you could never get on mainstream media... You would probably get five seconds of the image.

"But in five seconds you don't hear so much, you don't see so much, and you don't feel. But because we shot everything, people crying, people hurt, and people saw."

Despite Shufiyan's criticisms of the mainstream media, Malaysiakini's relationship with establishment news organisations is complex. Not only were nearly all of Malaysiakini's top news editors trained by mainstream news organisations, but they also use that training as a standard for professionalism.

Vicknesan ( right ), the editor in charge of letters, opinions, and columns, describes the nine years he spent at the government-run Bernama news agency as his "bedrock".

Vicknesan ( right ), the editor in charge of letters, opinions, and columns, describes the nine years he spent at the government-run Bernama news agency as his "bedrock".

Padmaja, who cut her teeth at the New Straits Times and Malay Mail , likewise notes that when people criticise the "mainstream media", she will ask "where do you think I got my training?"

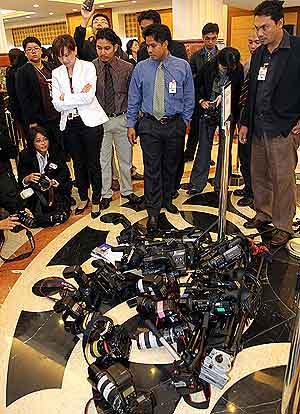

Moreover, the mainstream media have a symbiotic relationship with Malaysiakini . In some cases, individual journalists will send stories that they cannot use to their friends at Malaysiakini . Sometimes, when Malaysiakini reporters are denied access to official events, journalists from other news organisations will give them audio tapes of the meetings.

And although the establishment newspapers seldom quote Malaysiakini directly, preferring instead to use the term "an online news organisation", they will sometimes refer to stories that have been broken by Malaysiakini .

And although the establishment newspapers seldom quote Malaysiakini directly, preferring instead to use the term "an online news organisation", they will sometimes refer to stories that have been broken by Malaysiakini .

This usually happens when Malaysiakini's coverage of an incident or event has been picked up by Malaysia's active community of bloggers, who keep the issue alive until public pressure grows and the mainstream press is forced to follow suit.

According to R Nadeswaran, the deputy editor of The Sun newspaper, "the [mainstream media] wouldn't publish a press conference of the opposition party, but Malaysiakini could. And then other papers covered Malaysiakini ."

Part 1 l How Malaysiakini challenges authoritarianism

Part 2 l 'Our agenda is press freedom'

Part 3 l Holding the powers-that-be accountable

Part 4 l It's called 'watchdog' journalism

Part 5 l Do you have a valid point?

JANET STEELE is an associate professor of Journalism at the School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University. Her most recent book 'Wars Within' focuses on Tempo magazine and its relationship to the politics and culture of New Order Indonesia. She is a frequent visitor to Southeast Asia, and writes a weekly newspaper column called 'Email dari Amerika' for Surya daily in Surabaya, East Java.

Malaysiakini is celebrating its 10th year anniversary on Saturday, Nov 28 with a gala dinner at the Sime Darby Convention Centre in Bukit Kiara. Be there! Seats available from RM100.

Malaysiakini is celebrating its 10th year anniversary on Saturday, Nov 28 with a gala dinner at the Sime Darby Convention Centre in Bukit Kiara. Be there! Seats available from RM100.

Click here for more information.