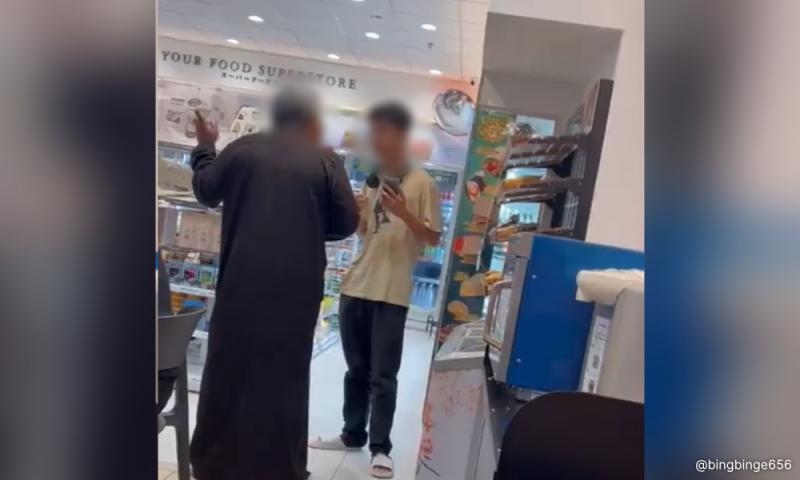

LETTER | The recent incident involving an older Malay-Muslim man and his physical assault of a younger Chinese man who was eating in public during Ramadan is, unfortunately, not an isolated incident.

That such an act is neither shocking nor surprising speaks volumes of how common moral policing is in Malaysia, and how some degree of violence is also, unfortunately, not unheard of.

Moral policing in Malaysia appears to be relatively limited to the Malay-Muslim community, where many people monitor and even enforce the religious activities of others, with such “vigilance” being heightened during Ramadan.

But as the above incident shows, such behaviour can erroneously affect our non-Muslim friends as well. So why is moral policing so prevalent in our community? And is it actually a good thing?

From a psychological point of view, moral policing in Malaysia could stem from something called the “social identity theory”. This theory states that people derive their personal identity from being members of a larger group.

A survey published in 2023 by the Pew Research Center found that 69 percent of Malaysian respondents believed that being part of the ethnic majority was a key factor in national identity, while 67 percent believed that being Muslim was also a key factor. In comparison, only 19 percent and 13 percent of Singaporeans felt that ethnicity and religion (Buddhism) were important for national identity, respectively.

This showcases how intertwined racial and religious identity is for the self-identity of many Malaysians. And for many Malay Muslims, this might explain their perceived responsibility to police those in their community. They feel the need to “protect” their community and their faith from transgressions, such as people who eat publicly during Ramadan. Though they may see moral policing as an altruistic endeavour, in reality, they may cause more harm than good.

If moral policing stems from good intentions, why does it so often result in conflict? In many cases where members of society police the behaviour of others, some may make false assumptions or end up going too far. The older Malay-Muslim man wrongly assumed the younger Chinese man was a Malay and made matters worse by physically assaulting him.

This might be explained by a psychological phenomenon known as “fundamental attribution error”. Many people are quick to judge the actions of others and attribute “bad behaviour” to flaws in their character, rather than considering alternative explanations. Like how one might assume someone eating in public during Ramadan is a “bad Muslim” rather than consider any alternative explanation, like the person eating is not a Muslim.

This phenomenon also explains how we judge others for behaving poorly, yet we excuse our own actions. The older Malay-Muslim man might have felt his actions were justified if he believed he was acting in service of his religion when in reality he unfairly judged and further assaulted the younger man.

Moral policing, if encouraged, would only lead to performative practices of religion. Fasting, praying, and other acts of faith would only be done to avoid judgement from others, and not out of sincere piety.

Furthermore, moral policing in Malaysia just won’t work because it relies on making assumptions about another person’s faith. Islam is not exclusive to the Malay community, yet those who “look Malay” will be policed, and this will wrongfully include non-Muslims as we’ve already seen.

Our non-Muslim friends should not be made to fear eating in public during Ramadan just because they look like a Malay. Being fundamentally flawed, we cannot and should not believe that an authoritarian approach is the way forward.

As humans, we are bound to make rash and often incorrect judgments of others. And those being judged will probably react negatively as well. Moral policing through verbal and physical abuse of others will only make matters worse.

As often is the case, the act of moral policing itself has been more damaging to the image of Islam than the originally perceived ill-behaviour which was being policed. Instead, those who wish to be a source of inspiration to their communities should lead by example. That is after all, how Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) acted.

Islam, like any other religion, is a deeply personal matter. Islam does not need enforcers. We can do much better by embodying the values of Islam through acts of kindness. As the saying goes, you catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.

JAZLI AZIZ is a senior lecturer at the Oral and Craniofacial Sciences Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Universiti Malaya, and may be reached at jazliaziz@um.edu.my.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.