Malaysians Against Death Penalty and Torture (Madpet) is shocked that the public prosecutor may be considering a proposal to deny bail for repeat offenders of small drug-related crimes that carry the penalty of five years’ imprisonment or less.

This was reportedly disclosed by Perak Narcotics Criminal Investigation Department head ACP VR Ravi Chandran who said there was a need to do so “... due to the increase of 12.2 percent, or 2,220 people, who were arrested for various drug-related offences last year” (‘Perak mulls denying bail for repeat drug offenders’, FMT News, Feb 2, 2017 and The Star Feb 3, 2017).

We recall the legal principle that every accused shall be presumed innocent until proven guilty, that is proven guilty after a fair trial.

The purpose of bail is simply that the accused person be released on condition that he turns up in court on the dates fixed for his/her case. Judges do consider all relevant factors, before deciding on the question of bail, which also may be granted on many other conditions, if needed.

As it is now, section 41B of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 already denies bail for persons charged with offences under the Act that carries the death sentences or sentences of more than five years’ imprisonment.

Section 41B 1(c), however, states as follows, “where the offence is punishable with imprisonment for five years or less and the public prosecutor certifies in writing that it is not in the public interest to grant bail to the accused person”. That means the public prosecutor will decide, and the accused has to stay in detention until the trial is over and the court decides whether he/she is guilty or not. This is unacceptable.

Judges should decide whether bail is to be granted or denied to an accused in any particular case. In bail applications, judges do consider all the arguments of the prosecutor and also the accused persons. Judges, after taking into account all relevant facts and the law, decide whether bail be granted or not, and if granted on what conditions.

It is wrong for Parliament through laws to oust this discretion of judges and/or courts. It is even more unjust, if that decision rests just in the hands of the public prosecutor.

What the Perak police are allegedly asking for is even more draconian, they want bail to be denied to all ‘repeat offenders’. It must be noted that some, especially the poor, even when innocent, do plead guilty especially for offences that carry lesser sentences.

Section 41B(1)(c) give the power of denial of bail to the public prosecutor, who simply has to certify “... in writing that it is not in the public interest to grant bail to the accused person...” Judges and courts power to decide on bail is simply ousted.

Worse still, the application seems to be for a blanket denial of bail for all persons charged with a drug-related offence, and this is unacceptable. This would include even persons allegedly with a very small amounts of drugs, possibly simply for personal usage. Every person’s application for bail should be considered individually.

There is great injustice when an innocent person is deprived of his liberty for so many months or years, and then found to be not guilty. As it is, trials in Malaysia can take a very long time, and it is possible some may have been detained for periods that are even longer than the maximum imprisonment sentence they would have faced if found guilty by court.

Denial of bail means not just the loss of liberty. It will also affect a person’s employment and income, a person’s business and other income generating activities. The impact will be also be felt by the family and dependants.

Now that Malaysia is a signatory of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, and by reason of the values Malaysians hold, we have to ask whether it is in the best interest of the child if her/his parent, brother or sister, is kept in detention even before the court finds/him/her guilty.

What is worse, is the greater injustice that befalls a person and also his/her family, if the courts finally determines that he/she is not guilty. Harm cause by this denial of bail can never be erased, and in Malaysia, at present there is still no law that provides for just compensation for those victims, whose freedom and liberty have been denied for so long.

‘Need for a law for just compensation’

It is thus important, that we, at the very least, have a law to provide for just compensation and/or damages to such persons, found to be innocent, for the time they had already spent in detention by reason of denial of bail, poverty, wrong court decisions that are overturned by higher courts, and even unnecessary detention by police for remand.

In some case, where there may have been justification to keep a person in detention and that person is finally acquitted and set free, he/she also needs to be compensation for the loss of liberty and freedoms, he/she had to suffer by reason of the said detentions.

The poor suffer the greatest when courts set bail at an amount which is too high and/or affordable to them and/or their family/friends. In Malaysia, where the bail is set at RM10,000, then the surety is expected to have that RM10,000 and be willing to part with it for the necessary duration.

A poor man earning RM1,000 per month, which is used to support himself and his family, when asked to post bail of even RM2,000 may find it almost impossible. A poor man’s family and friends also may not be able to afford to come up with that much. The end result is that even if bail is granted, but is unaffordable, a person may end up in detention until the trial is over.

Worse still is the situation when a person, who has been in detention by reason of denial of bail or being unable to afford bail, is finally found guilty for an offence where the maximum sentence is much less than the time actually spend in detention awaiting the end of trial. There is still no compensation for the extra unnecessary time spend in detention.

Some judges do consider the period the convicted has spend in detention when handing out sentence, and sentence them to the time spend already in detention which enables the convicted to immediately go free. But the doubt arises whether the same judge would have given a much lesser sentence if the same accussed had been out on bail pending conviction.

This bleak reality also results in many persons who may be actually innocent pleading guilty at the onset, because by so doing, they will just simply have to spend time in prison for a shorter defined period, and thereafter resume their ordinary life as soon as they get released. A great injustice happens.

Now, if bail is denied for minor drug related crimes, that carry sentences, if convicted, of imprisonment of five years or less, the naturally we may find many of these persons who are innocent or will never be found guilty, simply pleading guilty at the very start of the trial. It may good for the government, the police/enforcement officers and the prosecution to show effective law enforcement, but in actual fact it may not be true and a great injustice would occur.

As such, Madpet urges

a) That the question of bail must be always determined by the judges and/or courts, and certainly never the public prosecutor;

b) That all laws and/or provisions of law that deny the right to apply for bail, including Section 41B Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 be immediately repealed;

c) That right to bail is exercisable by all who are entitled, especially the poor. Bail amounts should be set taking into account the income of the accused and/or his immediate family;

d) That trials, where the accused are not out on bail, be expedited, and completed preferably not later than six (6) months;

e) That Malaysia enacts a law that will properly compensate the loss of liberty, freedoms and rights for those who have spend time in detention who is ultimately found not guilty and/or are acquitted. This compensation should also probably compensate the expenses incurred by the said accused (or even initially convicted) in his/her struggle than ended up in court finding him not guilty and/or acquitting him;

f) That Malaysia promotes and respects the human rights and freedom of all, including the right to a fair trial and the right to bail.

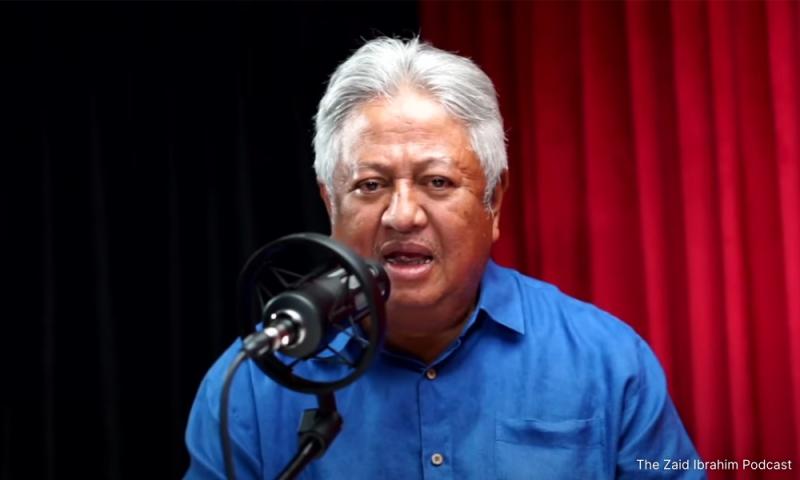

CHARLES HECTOR is coordinator, Malaysians Against Death Penalty and Torture (Madpet).