COMMENT | Two weeks ago, the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) published Belanjawanku (My Budget), an expenditure guide for individuals and families living in the Klang Valley. It has generated some debate amongst the Malaysian public, with most doubtful of the fact that it is possible for a single youth to rent a room for only RM300 in the area.

There was, however, no real public discourse on the RM30 budgeted for healthcare. Leaving aside those who have either purchased private health insurance or have health issues, respondents must be feeling very healthy and optimistic, and consequently likely did not think of allocating much of a health budget. A sum of RM30 would not be sufficient to secure any private insurance plan.

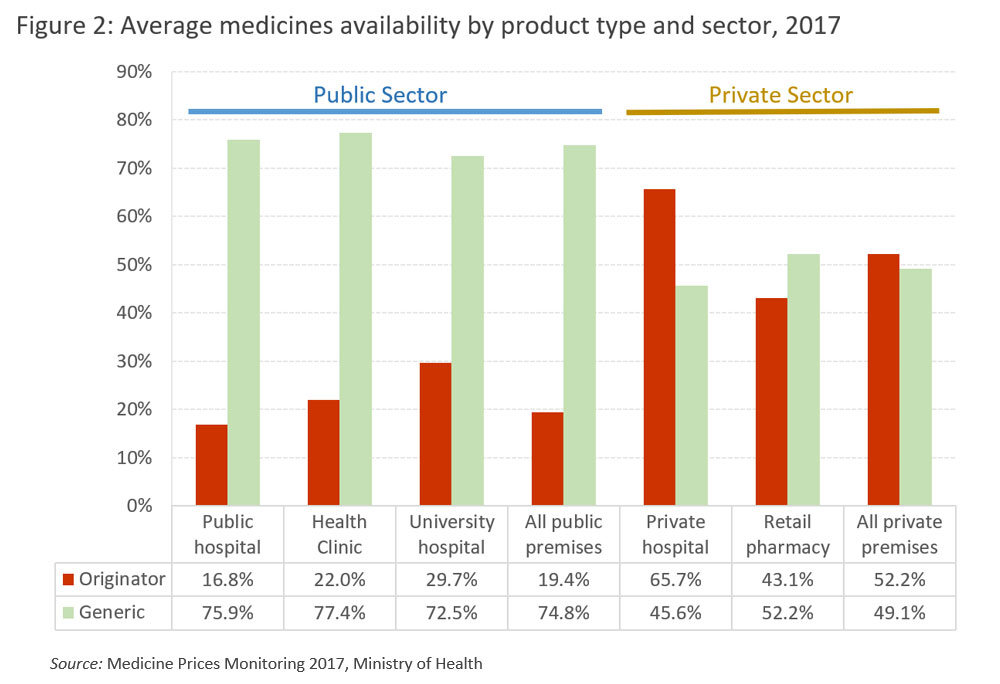

Granted, treatment for minor illnesses would likely be affordable under such a budget. This isn’t the case for more serious ailments, however. The 2019 Global Medical Trend Rates Report published by Aon, an international professional services consulting firm, forecasts net growth of 13.6 percent in Malaysia’s medical inflation rates for the current year – almost 5.7 times the forecast for inflation in general (Figure 1). The 2017 Malaysia National Health Expenditure findings also indicate that expenditure on medical goods already comprised 8 percent, or RM4.55 billion, of total health expenditure. This is a conservative calculation, one which does not include similar expenditures for inpatients.

Source: “2019 Global Medical Trend Rates Report”, Aon

Drugs take up 10 percent of MOH budget

The federal government in 2017 provided approximately RM2.4 billion for the procurement of medical drugs. This took up 10 percent of the total Ministry of Health budget in 2017. This expenditure item saw an increase of 13 percent relative to the preceding year, but medical supply shortages remain a problem in some public clinics and government hospitals - especially during the end of the year. This implies that the demand for public medical supplies still exceeds supply.

Unlike ordinary commodities, such as soft drinks where consumers are spoilt for choices and could always opt out from purchasing such products, the purchase of medicine is entirely different. Under normal circumstances, patients are left with no choice but to seek treatment, particularly if their illness demands immediate attention.

There are no alternative products to very specific drugs, especially when originator drugs are still under the patent protection period. This further limits the choices of a patient seeking alternative medicine. What really makes the difference is the phenomenon of asymmetric information within medicine, where the judgements and drug prescription decisions of doctors and pharmacists dictate or limit the choices a patient faces.

Some are led to believe that originator drugs must be more superior than generics in terms of quality, efficacy and safety, and are therefore willing to pay a much higher price for the originator even if they were told about the existence of its generic counterpart.

In Malaysia, after the successful registration of a drug patent, a product will usually enjoy a period of 20 years of market exclusivity. When the originator drug is still under intellectual property protection, it may be the market’s only option for a particular disease, and this is when the price a drug can fetch is usually at its peak.

Originator drug manufacturers normally consider the cost of drug production – including investment in R&D – and operating costs (including marketing), stakeholders’ interests, as well as consumers’ purchasing power and their willingness to buy the drug in a particular country, before they set the final price tag for their product.

The reality is that generic drugs have the same active pharmaceutical ingredient, dosage, administration route and functional effectiveness as originator drugs. It is only when the patent for the originator drug has expired that generic drugs are approved to be sold in the market. The production cost and sale price of a generic drug is generally significantly lower than that of the originator, even if the latter would later adjust their price to compete with the generic alternative.

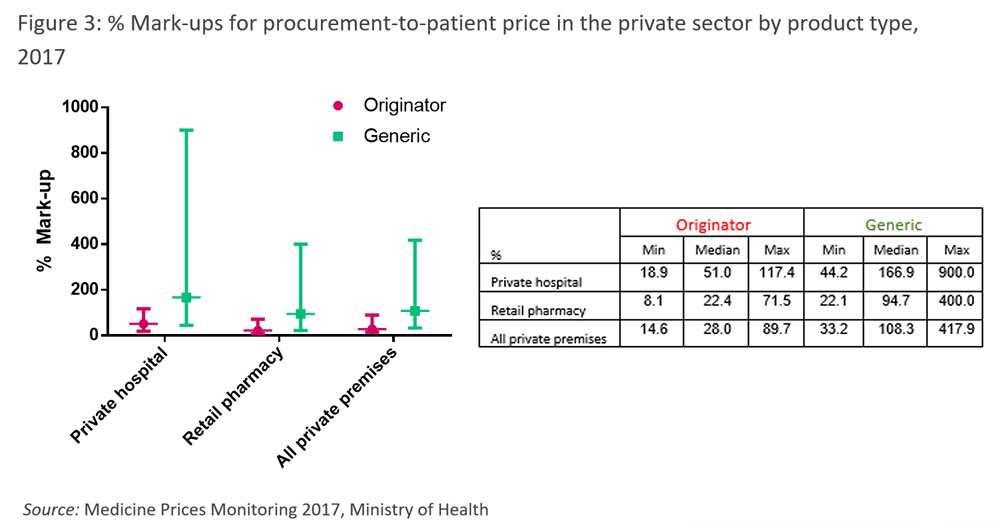

According to the Medicine Prices Monitoring 2017 report, the final retail prices for generics are on average three times cheaper than originators. Consequently, price-sensitive consumers typically choose generics. In 2017, the average availability of generics in the public sector was 74.8 percent compared to originators (19.4 percent) (Figure 2). This is in line with the national medicine policy which encourages the use of generic medicines. However, the private sector has a tendency to use originators more often, with an average availability of 52.2 percent.

In neighbouring Philippines, the law stipulates that the doctors and pharmacists must provide at least two generics (if they do exist) to accompany a prescription of an originator drug. This approach expands the availability of drug choices for patients.

In a normal medicine supply chain, drugs are produced by the manufacturer, ordered and shipped by importers, before changing hands to wholesalers or distributors who are in charge of the delivery of the products to the retailers (hospitals, clinics and pharmacies). Finally, they will reach the hands of patients or consumers. Due to the many levels of transactions within the supply chain, drug prices are inadvertently marked up at every level. Public healthcare system eschews the final retail-level mark-up, as our public healthcare system is tasked with providing medicine to the needy at almost zero cost.

Malaysia has a pharmaceutical manufacturing sector which produces almost entirely generic drugs, with sales revenue amounting to only a quarter of the total revenue of the pharmaceutical industry in 2014-2015. Some 61 percent of drugs (of equivalent revenue value) are imported, and amongst those, 87 percent of revenues were in the hands of local proxy companies for the big multinational pharmaceutical manufacturing companies. The top five companies take 47 percent of total medicinal imports, and importantly, these big multinational pharmaceutical parent companies get to decide the drug prices across countries, and they normally sell originator drugs.

Although local importers and sales proxies representing the top five multinational pharmaceutical companies did not have a big net profit margin (in between 1.6 and 3.4 percent), the average net profit margin for their parental companies is 26.2 percent - about 10 times that of their local importers! This market phenomenon indicates that the drug price-setting practice and global sales has laid golden eggs for Big Pharma companies, and left a bitter taste for patients and governments who have to make these purchases. Critics often point out that the market behaviour of the pharmaceutical companies has a significant impact on global medical inflation.

Distributors only work for the clients, provide logistics, and storage and services support, but do not own any stock of medicine. This is so they would not have influence over market pricing. A market review report shows that the mark-up by wholesalers or distributors was marginal, at 2-3 percent. However, when the products reached the retailers – such as medical institutions and pharmacies – the mark-up is different.

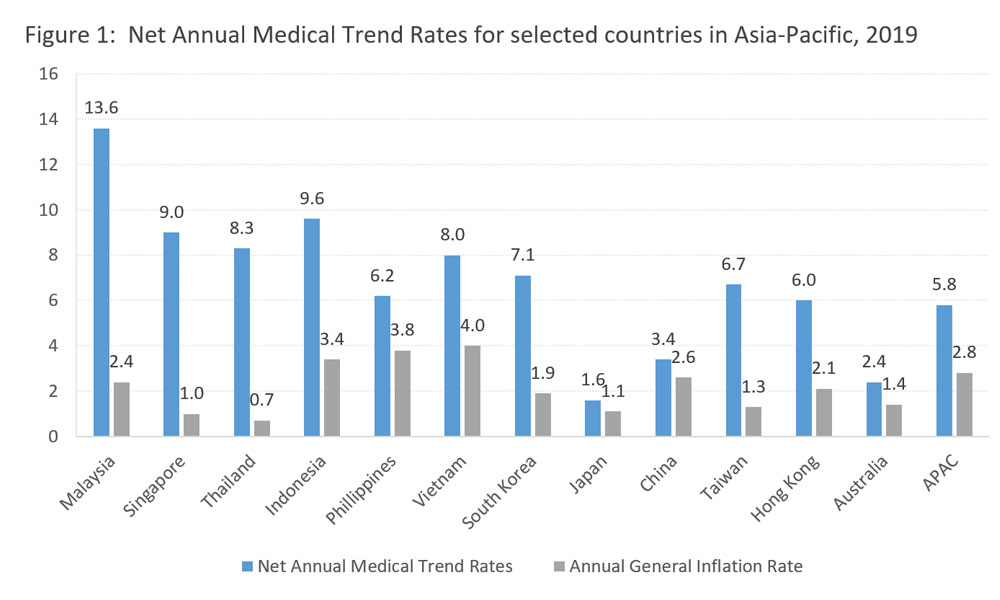

According to the Medicine Prices Monitoring 2017 report, the median mark-up for originators’ and lowest-priced generics’ retail price in private hospitals was 51 percent and 167 percent, respectively, whereas in pharmacies these figures were lower, at 22.4 percent and 94.7 percent (Figure 3). This shows that the mark-up range can be exceedingly large; in some extreme cases, in private hospitals, these could even spike up to 117.4 percent and 900 percent! Due to the lower production or import cost of generic drugs, this allows private hospitals, clinics and pharmacies the opportunity to further mark up the final retail price which results in higher prices across the board, but greater profits.

Those in the sector often claim that price setting operations for medical products are within the bounds of the free market, or in other words, that mark-up behaviour is totally within legal boundaries, although it is considered by many to be unethical. Particularly when the prices for prescription or controlled medicines are hardly transparent, it is difficult for consumers to clearly compare prices and make informed decisions. In fact, the free market dogma entails that prices be made transparent so that the market could be made more efficient, with consumers making the best decision for themselves!

However, the situation we have now often ‘encourages’ retailers to raise their prices arbitrarily while patients or consumers are not properly informed. Patients receiving medical treatment services often find that medicinal purchases constitute the most significant expenditure item in medical bills; this indicates that the mark-ups set by medical institutions undeniably add to patients’ financial burdens.

Two months ago, I participated in a conference on rising medical costs. Throughout the conference, representatives from the participating multinational pharmaceutical companies, local private hospitals, as well as chain pharmacies all claimed that their profits are entirely justifiable because margins are reasonably low. A representative of a local chain pharmacy even commented to the audience that the large volume of medical products they sold was only of such a small profit to them that they have to diversify and rely on selling ice cream to subsist! This claim blatantly contradicts what data indicates.

Dealing with the factors contributing to rising drug cost, the Ministry of Health has mooted the introduction of a mechanism to control medicine prices. This would be an interesting, if complex and challenging, proposal. Besides this, the pharmaceutical services department under the ministry is making efforts to increase the transparency of medicine prices.

Therefore, since 2015 a Consumer Price Guide has been uploaded on the ministry's website to enable people to make price comparisons. In the name of fairness and transparency, I hope the private sector takes the initiative to display all retail medicine prices to allow the public to make informed judgements. After all, for a laissez-faire market to work efficiently and effectively, there should be a free flow of pricing information for consumers to make the most economical decisions.

LIM CHEE HAN is a senior analyst in the political studies section at Penang Institute. He holds a PhD in infection biology from Hannover Medical School, Germany.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.