COMMENT | There he is, a little boy walking barefoot with a bucket of fish in one hand and holding a younger girl in another. They are walking slowly on the street, asking all around to enquire if there are any willing buyers for the bucket of fish the boy is holding.

But with the morning market just a mile away, buying fish from this boy will not be a favourable option to many Sabahans. And the boy and girl are just one of the many stateless children in Sabah.

In Sabah, resolving issues such as poverty and stagnating development are challenging enough for the newly-formed state government.

Perhaps what is even more worrying is the growing number of stateless children in Sabah. They have lived amongst ordinary Sabahans for many, many years.

In 2016, Al Jazeera’s "101 East" even produced a special report titled "Sabah’s Invisible Children."

A complicated issue

The problem of stateless children in Sabah can be traced back to the late 19th century, when Sabah was formed as the crown colony of North Borneo administered by the British Empire.

The geopolitics between Sabah and the Philippines, as well as the close proximity between the two countries, has given an opportunity for people to travel or even move between the two.

Shortly after both Sabah and Philippines achieved independence, however, the freedom of this group of people, who were known as the nomadic Bajau Laut was restricted by the fence of nationality.

Some of them used to live in between Philippines, and Sabah – especially its east coast. In addition, they also preferred to earn their living and live their lives on their boats. These vessels also ensured more mobility to move around.

Most of the Bajau Laut cannot even tell you where they belong, because they view themselves as “freemen”.

In my view, stateless people in Sabah can be divided into two categories: the undocumented indigenous living in remote areas, and undocumented migrant or stateless descendants.

Some of the stateless people in Sabah are those living inland or in remote areas. They were unregistered due to first, the lack of knowledge or awareness of the importance of registering oneself with a specific nationality, and secondly, abject poverty.

However, such stateless people are relatively easy to handle from the point of view of the state government.

On the other hand, managing undocumented migrants and stateless descendants is a far more complex prospect.

This group of people are stateless because their parents are unable to provide legal documentation for their marriage. As a result, newborns to this group are unable to obtain birth certificates, and this renders them stateless.

Some may be second-generation stateless children, born out of stateless parents. Most of them would view Sabah as their homeland as they were born and have lived there all their lives.

I personally agree with a name or label that was used by a former University of Sabah professor, Fadzilah Majid, to describe this group of people – the "Other Sabahans."

The cycle of statelessness

The 1954 United Nations Convention in relation to the Status of Stateless Persons aims to ensure that stateless people enjoy a minimum set of human rights.

Undoubtedly, nationality gives people a sense of identity, and more importantly, nationality is the insurance whereby citizens are – at the very least – granted a modicum of rights and freedoms.

The inability of the ‘other Sabahans’ to obtain identification and travel documents, however, effectively denies their rights to the freedom of movement.

Having endured the status of statelessness for a long time, this large population group can have a serious impact on the stability of society.

A news outlet reported that half of the estimated 1.3 million working non-Malaysians in the country – a group comprised of the undocumented, the stateless, and legal migrants – are living in Sabah.

The locals often blame stateless children for a range of social ills, as most of them are poor and illiterate, and this renders them the most vulnerable community in Sabah.

They might resort to petty theft or begging for money in urban areas just so they can subsist for another day. The most unfortunate ones may even develop drug addictions.

Without proper documentation, it is difficult for this group of people – especially stateless adults – to secure proper employment and escape the trap of poverty.

It will then leave this group of people stuck in the cycle of statelessness and poverty, with no access to public healthcare and education. Remember, many of these are second- or third-generation stateless people who self-identify as Sabahan.

Possible solutions

Some NGOs in Sabah have started to organise educational programmes for stateless children to receive basic education, but this is unlikely to be a programme that is sustainable in the long term.

Even in the event that these children achieve excellent academic results, they will eventually be deprived of tertiary education opportunities due to their identity problems.

In response to the aforementioned challenges, the Sabah state government has embarked on the ‘mobile court’ service, which started around 11 years ago.

The mobile court is set up in special modified buses, with officers assigned for each court service visit. The mobile courts go deep into the state’s interior, to help with and resolve issues related to birth registration for stateless children.

To register and confirm the late birth registration, parents need to bring along supporting documents such as clinic check-up reports, marriage certificates, and witnesses to present to the judge or a magistrate that station in this mobile court.

Local news has reported that the mobile court service has assisted in the processing of 40,000 stateless cases.

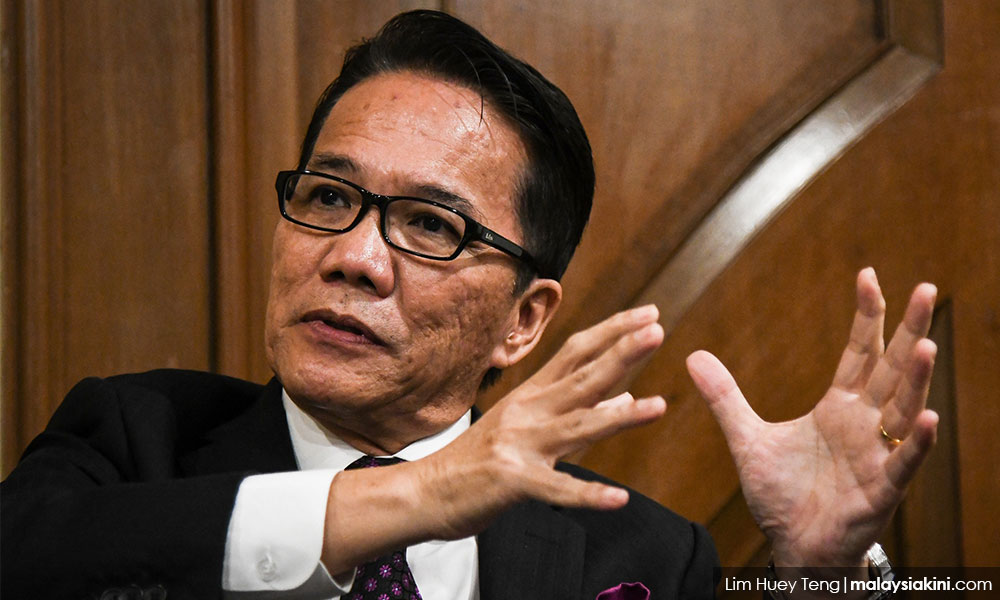

According to de facto Law Minister Liew Vui Keong, the federal government is looking into the statelessness issue, and is working closely with related organisations and government departments to come up with better solutions.

At the moment, the mobile court service is the only viable option and solution. However, this solution can only provide help to indigenous groups living in remote areas who have not registered themselves due to financial or logistical issues.

Besides, another action that the government should consider taking is to strengthen border security checks and to conduct daily checks to track down undocumented migrants and their children.

For example, Kampung Air near the city of Kota Kinabalu and Sepanggar Bay are well known as ‘undocumented migrant hideouts’ and stateless ‘production sites’.

Therefore, I believe that severely reducing the undocumented migrant population should be the primary action and strategy. Some of the immediate actions that can be taken are to empower the Immigration Department or other related departments that are in charge of immigration matters.

Effectively eliminating or at least substantially reducing the number of undocumented migrants can at least put a halt to the continually rising number of stateless children.

Furthermore, the reality of Sabah needs to be taken into account. The federal government may be willing to work with the relevant government departments to hammer out solutions, but these would be inadequate without the input of local expertise.

Some plans may work for other states but given its unique circumstances, the statelessness issue in Sabah does require a different approach.

For example, starting this year, stateless and undocumented children will be able to be enrolled in government school provided that their parents or guardians are able to present documents such as the child’s birth certificate or official adoption letter.

This policy may turn out to be effective in solving the problem by giving this group of children basic rights to education, but it neglects the fact that many stateless children do not even have such documents to begin with.

Another factor that the federal government should consider is whether the existing schools, teachers and teaching materials in Sabah can afford a sudden increase in the number of enrolments. As of today, there are an estimated 50,000 undocumented children in Sabah without access to education.

This is why the federal government must allocate greater financial and human resources to the Sabah Education Bureau, to ensure such a policy is a success. The idea of decentralising education policy to the Sabah state government should also be placed under consideration, taking into account the circumstances in Sabah.

On the other hand, while waiting for the implementation of such a policy, our federal government ought to face the United Nations and proceed to sign international conventions related to human rights.

During Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s speech at the 73rd UN General Assembly, he vowed that Malaysia would firmly support the principles of human rights, the rule of law, justice and fairness as advocated by the United Nations, and promised to ratify all UN conventions related to human rights.

This includes giving stateless people the basic human rights they desperately need. As long as they meet the conditions of residence, they can apply for and hopefully obtain long-term residence permits and citizenship according to proper procedures.

Acceptance should be given to this group of people, who have been among us longer than Malaysia has been an independent nation.

ESTHER SINIRISAN CHONG is an analyst and administrator at Penang Institute in KL. Trained in International and Strategic Studies and History at University Malaya, she was born and raised in the Land Below the Wind. Her research interest lies in education and government policy, history and heritage of East Malaysia.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.