COMMENT | I was honoured to learn from media reports on Wednesday of my own nomination to the Election Reform Committee (ERC) in the Prime Minister’s Department.

But where would this ERC be placed in the whole picture of electoral reform? How does it fit in with the reform of the Election Commission, the establishment of a parliamentary select committee and/or a commission of inquiry for electoral reform?

Where does it stand in relation to the recommendations of the Institutional Reform Committee (IRC), which covered electoral reform in its report to the Council of Eminent Persons (CEP)? Do we need multiple vehicles for one mission?

I would like to share my view on the big picture of electoral reform as Malaysians are celebrating their second Merdeka. For a people are not free until they can freely choose their governments.

What needs reviewing

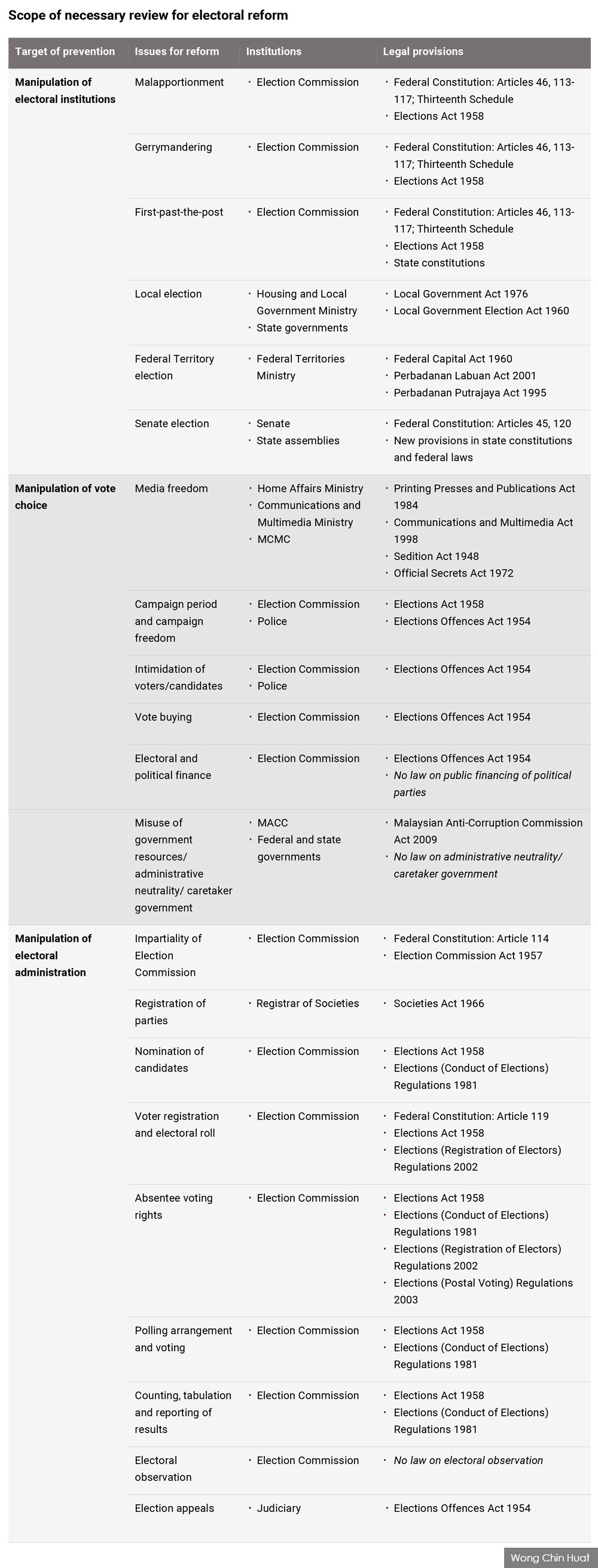

Political scientist Sarah Birch categorises electoral malpractice into three types: manipulation of electoral institutions, manipulation of vote choice, and manipulation of electoral administration.

Based on Birch’s framework, there is a whole laundry list of what needs to be done in Malaysia, as laid out in the table below. Keeping the whole picture in mind is important because Malaysia should go beyond fixing malpractices in isolation, and consider a paradigm shift from a winner-takes-all system to a “consensus democracy”, which is more suitable for a society deeply divided along ethnic, religious and lifestyle lines.

All changes listed in the table require parliamentary approval. Not only constitutional amendments require a two-thirds majority, even by-laws governing the conduct of elections and postal voting need to be laid before the Dewan Rakyat.

Ultimately, changes to electoral institutions need to be considered with other reforms in a package. Overcoming inter-state malapportionment in Dewan Rakyat or changing its electoral system may require over-representation of Sabah, Sarawak and smaller states in an elected and empowered Dewan Negara. Likewise, introducing local and federal territory elections should go hand-in-hand with decentralisation to empower the states.

What has been studied

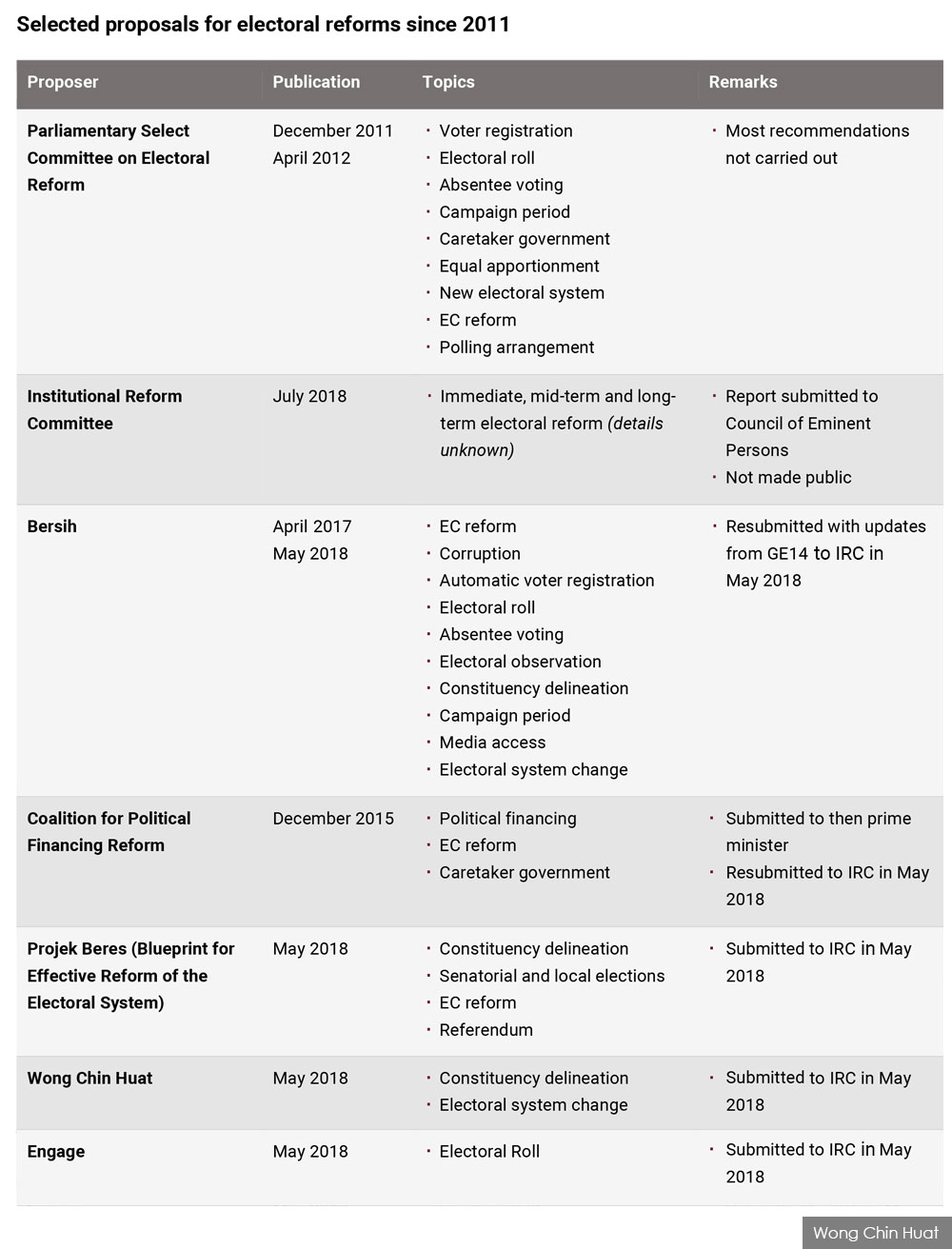

Fortunately, many of these topics have already been studied by both state and non-state actors.

A Parliamentary Select Committee on Electoral Reform was set up in 2011 after the Bersih 2 rally, which produced two reports – one in December 2011, and the second in April 2012, both covering a total of 29 topics. Unfortunately, most of the recommendations were left unexecuted.

The wealth of research conducted means that the wheel does not need not be reinvented.

For instance, Bersih has produced a series of comprehensive and detailed studies, such as its reports before and after the May 9 polls. And it would be difficult to produce a better report on political financing reform than the one written by economist Edmund Terence Gomez, which was backed by 70 NGOs led by G25.

Research on these issues have also been conducted by Projek Beres (Blueprint for Effective Reform of the Electoral System), Engage and myself, the reports of which were submitted to the IRC.

For areas in which thorough research has been carried out, proposals should just enter the implementation stage. But to know if sufficient research has been carried out, the IRC report to the Council of Eminent Persons covering electoral reform must be released.

The leading legal minds in the IRC and its supporting researchers have diligently looked through dozens of proposals to prioritise recommendations for action. Any further study should only be limited to selected topics that require greater depth and wider engagement, not repeating IRC’s groundwork.

When to implement?

Any reforms pushed back until after the next general election will be meaningless. The deadline, however, is not July 2023, when the 14th Parliament completes its term, but June 2021, when Sarawak’s 18th Legislative Assembly will be dissolved, just some 33 months away.

Considering that early elections can be called at any time, along with by-elections to fill vacancies, no time should be lost in implementing basic reforms pertaining to the electoral roll, voter registration, absentee voting, polling and counting, campaign freedom, and electoral observation.

Indeed, the EC should already have started to work on providing absentee voting facilities to ordinary citizens so that Sarawakians working, studying or living out of state need not fly home again just to cast their ballot in 2021.

Next on the order of urgency, but with the same deadline, are matters that pertain party competition in general – such as EC reform, registration of parties, electoral and political financing, caretaker government regulations, election offences, and media access.

Despite a wealth of technical studies already carried out, most of these reforms do not currently fall under the EC’s purview. As such, the real work lies in forging cross-party consensus and inter-agency coordination.

A change to the electoral system is also overdue, possibly accompanied by decentralisation and parliamentary reform.

The potential price of keeping the current first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting system includes communal anxieties, political radicalisation, implosion of the ruling coalition, and the persistent underrepresentation of women.

Read more: Roadmaps for electoral reform

Practically, electoral system change is more urgent than many may realise. The last constituency delineation exercises for Malaya and Sabah (unenforced) were done in outright violation of the Federal Constitution, but the recommendations stay for eight years under normal circumstances.

As a quick fix under the FPTP system would require constitutional amendments, it may make more sense to consider bringing in a party-list proportional representation (List-PR) component. I am therefore pleased to read the ERC’s intention to consider a new electoral system.

Who to carry out reforms?

To implement, or at least commence reforms in the next 33 months (or 58 at the latest), a multi-vehicle approach is necessary for both the division of labour and consensus-building, involving parliamentarians, parties, NGOs, government agencies, and the public.

First, the EC must be immediately revamped – not just a new chair, but an entirely new commission to quickly embark basic reforms. No time should be lost.

Second, a parliamentary select committee must be formed on elections and multi-party democracy to permanently oversee matters related to elections and political parties, and approve nominations for future chairpersons and members of the EC.

Reporting to the prime minister, the ERC can play a catalytic role to complement the revamped EC and the parliamentary select committee. It can study and forge a broad consensus on a range of issues, from political financing to the electoral system, before legal and constitutional amendments are scrutinised by the parliamentary select committee and passed by Parliament.

Instead of producing a whole report at the end of its two-year term, the ERC can produce topical reports at times for reforms to be carried out in installment.

If necessary in the later stage, a royal commission of inquiry (RCI) can be tasked to recommend a systemic overhaul of Malaysian democracy, covering electoral system change, federalism and parliamentary reform in the true spirit of the Malaysia Agreement 1963.

For the ERC to play a productive and integrating role in building consensus for electoral reform, it can start by asking for the IRC report to the CEP to be made public as a green paper, and its reports – with room for minority opinions – to be made white papers.

I wish the electoral reform a great success with the ERC under Abdul Rashid Abdul Rahman’s leadership and am happy to serve the cause.

WONG CHIN HUAT studies electoral, party and identity politics in Malaysia. He is head of the political studies programme at Penang Institute.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.