As Malaysia positions itself to ride the wave of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), its focus on innovation and technology has never been more crucial. Malaysia’s rise to 33rd place on the Global Innovation Index (GII) is a testament to the nation’s unwavering commitment to cultivating a dynamic ecosystem where innovation can flourish.

At the forefront of the nation’s innovation advancement mission is Dr Rais Hussin, CEO of Malaysian Research Accelerator for Technology and Innovation (MRANTI) who’s no stranger to the technology and innovation sphere. A prominent entrepreneur, strategist, and policy intellectual, Rais previously served as the chairman of the Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC).

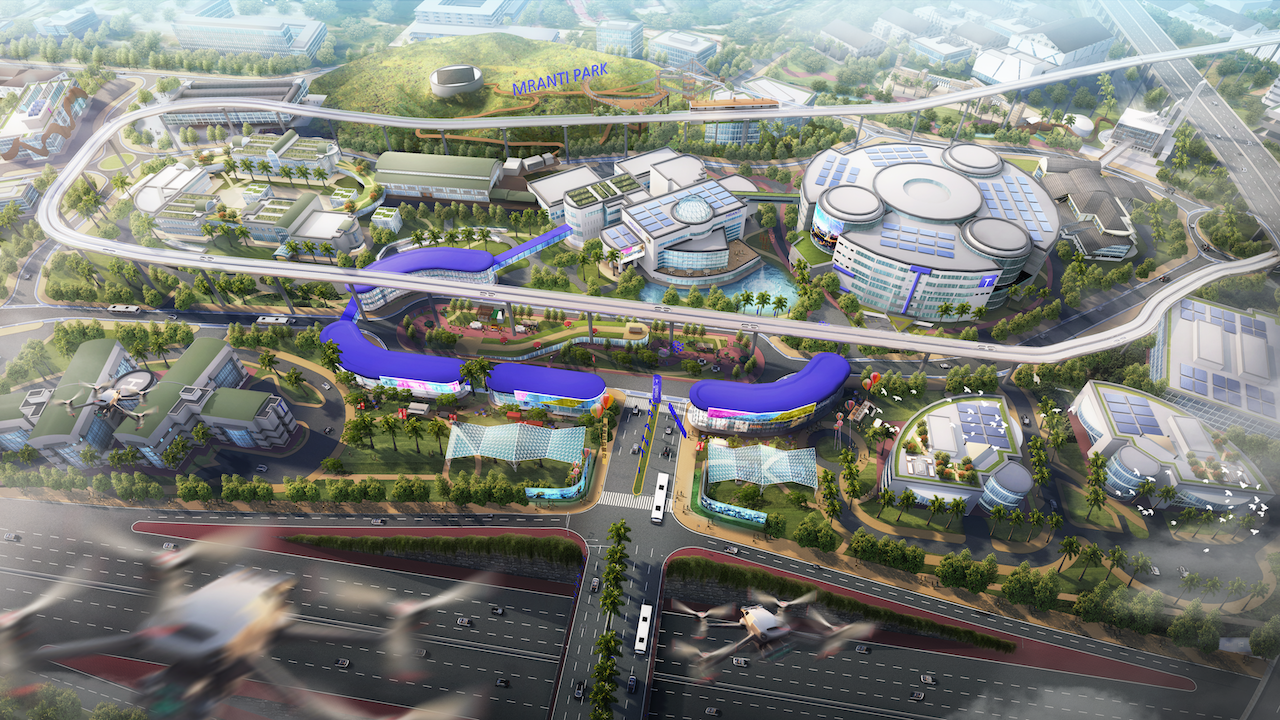

As the head of MRANTI, he has taken a focused and proactive approach to strengthening Malaysia’s innovation ecosystem, centring on addressing national challenges. He has successfully obtained substantial government funding to upgrade MRANTI Park’s infrastructure, with the goal of transforming it into a world-class innovation hub.

Under Rais’ leadership, MRANTI is in the midst of a rebranding exercise, now known as Technology Innovation Park Malaysia (TiPM), to reinforce its global presence and mission. This reflects the corporation’s commitment to recalibrating its focus and realising its vision of becoming a nucleus for innovation.

TiPM: The new chapter

With its rebranding, TiPM/MRANTI aims to accelerate demand-driven research and development (R&D) and address pressing national concerns, including food and health security. The organisation is intent on ensuring that innovations are not just theoretical but practical and impactful. This mission aligns closely with Malaysia’s need to transition from a technology consumer to a technology producer.

Addressing food security through technology

One of the pressing challenges Malaysia faces is its staggering food import bill. Drawing on international success stories from India, China, and Qatar, TiPM seeks to implement innovative solutions that are both scalable and sustainable.

“Many countries have resolved their food security issues through the use of 4IR. India, for instance, despite its population of 1.475 billion, through mechanisation, automation, and 4IR, it is now able to export 25 million metric tonnes of rice a year,” said Rais.

“One of the mandates that has been given to us is addressing the national food security agenda through the use of 4IR.”

Breaking down ‘territorial excellence’

A significant cultural challenge in Malaysia is the siloed approach of government agencies, dubbed “territorial excellence”, which often inhibits collaboration and innovation.

Rais highlighted the importance of fostering a culture of collaboration, drawing inspiration from countries like Sweden, which ranks high on global innovation indexes. In Sweden, cohesive inter-agency efforts and mission-driven goals have been instrumental in driving innovation.

Tackling brain drain

Malaysia’s brain drain remains a critical issue, with around 500,000 skilled professionals leaving the country in the past decade.

“And guess what? These are from the age group of 27 and above with the right skills, knowledge, abilities and experience. And where do they go?

“The number one country that they go to is Singapore, and then New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom and the others,” said Rais.

While competitive salaries abroad are a factor, the underlying issue is the lack of a robust ecosystem that nurtures talent and innovation. TiPM/MRANTI aims to address this by creating an environment that not only retains talent but also attracts it from abroad.

Turning R&D into impactful products

One of TiPM/MRANTI’s primary goals is to tackle the longstanding issue of “shelf research” - government-funded research that never sees the light of day.

“The government has spent a lot in terms of R&D, but the majority of them sit on shelves somewhere without the opportunity for their impact to be realised. That’s very unfortunate! This is where we step in as a technology commercialisation accelerator, bridging the gap between research and commercialisation,” MRANTI chief ecosystem officer, Safuan Zairi, explained.

“How do we help bring all these great ideas captured in research? We bring in our ecosystem partners - universities, start-ups, and industries - to create a technology commercialisation value chain. We look at it from the viewpoint of technology readiness,” he added.

Learning from global success stories

TiPM/MRANTI draws inspiration from successful innovation hubs like Zhongguancun Science Park (also known as Z-Park) in China, which has created numerous unicorn companies through a robust innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem. By adopting similar strategies and learning from their journey, it hopes to position Malaysia as a competitive player in the global innovation landscape.

Hidden cost of inaction

The government’s expenditure on projects, often understated in official figures, reveals a complex web of inefficiencies. A critical factor is the reliance on rudimentary models, such as applying a basic multiplier of one to estimate economic impact, which vastly underrepresents the potential value of investments. This oversight points to larger systemic issues, including inefficiency, poor execution, and brain drain.

Rais aptly noted the lack of proper execution undermines even the most well-crafted plans. For example, Malaysia’s Agricultural Master Plan, hailed as a blueprint for achieving food security, remains largely unrealised due to entrenched obstacles like cartels and the absence of stakeholder ownership.

Innovation as a national priority

Malaysia’s ambition to rank within the top 30 of the Global Innovation Index by 2030 demands a focus on transitional research that bridges the gap between academic pursuits and real-world applications. The key lies in enhancing commercialisation efforts. Lessons from countries like South Africa underscore the pitfalls of prioritising outputs over outcomes, such as achieving a high commercialisation rate without addressing genuine market needs.

A framework for success: IOOI and outcome-driven strategies

The IOOI (Input-Output-Outcome-Impact) framework emerged as a pivotal tool for ensuring accountability and focus in project execution. Unlike traditional metrics that prioritise inputs and outputs, the IOOI framework emphasises outcomes and impacts.

For instance, investing in technology to improve digital literacy among students can create ripple effects, enabling economic empowerment for families.

This approach aligns with best practices from certain countries, such as Singapore, where every dollar spent is tied to measurable outcomes. Emulating such models can help Malaysia overcome its fragmented reporting culture and shift focus from procedural compliance to strategic impact.

Balancing short-term wins and long-term goals

One recurring theme was the tension between achieving quick wins and pursuing long-term objectives. The rolling plan (annual) request for budget under the five-year planning cycles following the Malaysia Plan framework often compels agencies to prioritise immediate results, which may dilute broader, transformative goals.

“As it is, for every agency, we need to deliver results within one year for guaranteed funds in the following year. This will motivate agencies to execute initiatives that are easier and simpler versus more comprehensive action plans,” revealed chief strategy officer Khalid Yashaiya.

He noted that some countries, such as Sweden, use an alternative approach, focusing on a few clear national missions.

“Sweden has their plans. They have a mission, and it’s very simple. They focus on, say, for example, five target areas. Again, just an example, they want zero hunger. Everyone would know that there is a four-year target.”

These long-term targets encourage sustainable collaboration and innovation without the constant pressure of short-term deliverables.

Towards a unified ecosystem

A fragmented ecosystem with overlapping mandates among government ministries remains a significant hurdle. To address this, fostering better coordination and clarity of roles is critical. Collaboration among agencies like MDEC and Cradle Fund can ensure that efforts in emerging fields such as autonomous technologies, life sciences, and sustainable agriculture are cohesive and impactful.

The path forward

Despite the challenges, Malaysia’s commitment to innovation and sustainability remains steadfast. By leveraging frameworks like IOOI, fostering local talent, and embracing a culture of accountability, the nation can position itself as a leader in the global innovation landscape.

The goal is not merely to chase metrics but to create meaningful, lasting impacts. This requires a delicate balance of ambition, strategy, and execution - qualities that, if harnessed effectively, can propel Malaysia into a brighter, more innovative future.