COMMENT | On Sept 20, I wrote about the significance of a political pact signed six days previously between Umno president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi and PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang. To quote me:

"The overriding fear among non-Muslims in Malaysia now is that the Umno/PAS charter normalises hate speech towards minorities. This charter sends a powerful message to religious right-wing groups in Malaysia that it is open season on non-Malays. The charter’s message seems to be this: Malaysia is for Malays and Muslims only."

I did not expect my prediction to come true so quickly. On Sunday, Oct 6, at the Malay Dignity Congress, the main organiser, Zainal Kling, said in his opening speech that Malaysia is for the Malays and those who oppose (read: non-Malays) the "social contract" and Islam’s position as the official religion have to be fought against.

He even threatened non-Malays that if they oppose the "social contract" then the Malays should suspend it; i.e. suspend citizenship for non-Malays. In some countries, his entire speech would probably fall under the umbrella of hate speech.

The message is loud and clear: non-Malays who wish to call themselves Malaysians must subscribe to the ideology of Ketuanan Melayu and thus accept their lot as second-class citizens.

The "social contract" Zainal was referring to is the supposed quid pro quo agreed during the negotiations leading to Malaya’s independence in 1957. According to this version, the non-Malay leaders in the Malayan Alliance agreed to the principle of Ketuanan Melayu (Malay supremacy) in return for citizenship for the non-Malay population.

Reputable historians of Malaya do not have a consensus on this issue. There are no historical records or official papers to show that the non-Malay Alliance leaders explicitly agreed to Malay supremacy forever in return for citizenship. Private papers of the leaders who were at the negotiating table are crystal clear, however, that there was no explicit notion of Malay supremacy in perpetuity.

Moreover, the term "social contract" was not even used during the negotiations in the 1950s. Its first usage was in 1986, when Abdullah Ahmad, former political secretary to Abdul Razak, Malaysia’s second prime minister, gave a speech in Singapore in which he said the following:

"The political system of Malay dominance was born out of the sacrosanct social contract which preceded national independence. Let us never forget that in the Malaysian political system, the Malay position must be preserved and that Malay expectations must be met."

Despite doubt surrounding its origins, the term "social contract" is now widely used in Malaysia, and the common understanding of the social contract is Ketuanan Melayu = citizenship for non-Malays. In other words, equal citizenship will never be available to the non-Malay population, not now and not ever. The idea of the social contract is used every time Malay politicians want to defend discriminatory policies against non-Malays. In other words, the present non-Malay generation must pay for the sins of their forefathers.

Although media attention focused upon Zainal’s speech, the real significance of the Malay Dignity Congress was not what was said, but who was sitting in the front row. The top leadership of all the Malay-majority parties were present, from PAS, Umno and PKR to Bersatu. Countless Islamic non-governmental organisations (NGOs) were also represented, and all of the politically influential religious leaders were present, including the outspoken mufti of Perlis.

Four Malaysian universities, including Universiti Malaya, the most prestigious university in the country, were listed as co-organisers, with the vice-chancellor of UM giving a speech which warned non-Malays not to challenge the social contract.

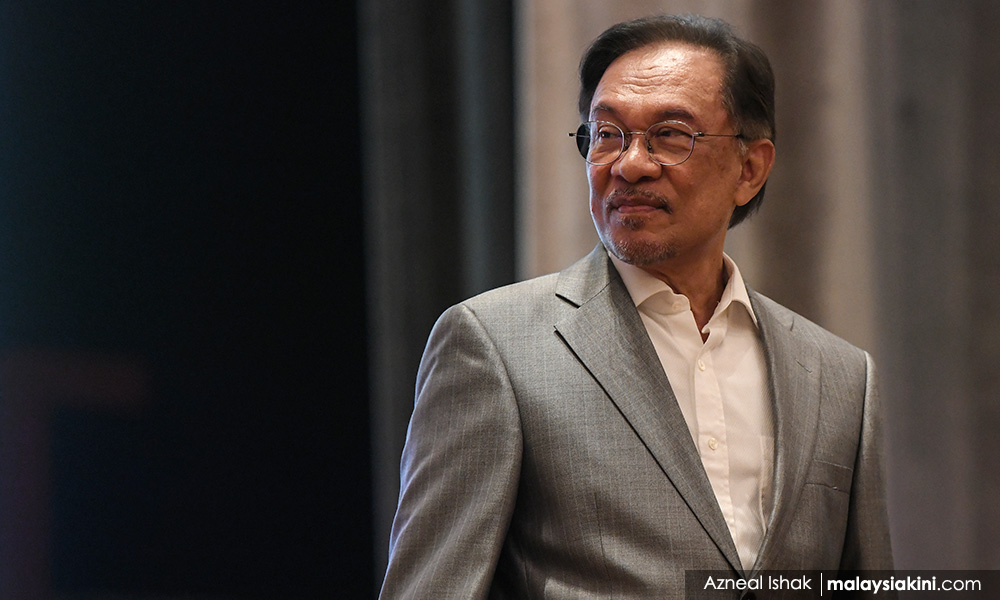

The keynote speech was given by Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad himself, leader of the Bersatu. A picture posted on the wall of Mahathir’s Facebook account shows all the leaders holding their hands in unity. The only party leader missing was Anwar Ibrahim, leader of the PKR. He was missing from the event because he was not invited; the invitation went to his deputy Azmin Ali instead. This was an open snub by the right-wing Malay establishment, indicating that they do not want Anwar to be the next prime minister.

The fact that all of the key Malay politicians, from both the government and the opposition, were willing to attend the gathering despite knowing its clear agenda of promoting Malay supremacy – and thus institutional racism against non-Malays – suggests without doubt that the Umno/PAS pact signed in September had the desired effect of openly pitting Malays against non-Malays.

It is testing the waters for the notion that Malaysia can be ruled by the Malays alone with no input from non-Malays. The message is loud and clear: non-Malays who wish to call themselves Malaysians must subscribe to the ideology of Ketuanan Melayu and thus accept their lot as second-class citizens.

What was even more incredible was that the event was held at the same time that members of Malaysia’s ruling alliance, the Pakatan Harapan were holding a retreat at a hotel less than 10km away. Among those taking part in the retreat were the DAP and Warisan, a multiracial party from Sabah.

I’m trying to imagine what the DAP and Warisan members of parliament (MPs) were thinking when they saw Mahathir and Azmin Ali holding hands with top leaders from Umno and PAS and other right-wing Malay groups, while the official Harapan government policy is one of "shared prosperity" and inclusion. In fact, just 24 hours earlier, Mahathir launched the Shared Prosperity Vision (SPV) 2030, promising national unity and to narrow the country’s inter-ethnic income gap to below 10 percent by 2030.

While many non-Malays expected DAP leaders to react immediately to the openly racist congress proceedings, it was actually the statement by Darrell Leiking, the deputy president of Warisan, that lit up social media. Leiking was the first senior non-Malay leader to call out the congress for blaming non-Malays every time the Malays needed a scapegoat for the community’s problems. He also reminded everyone that "Malaysia for the Malays" would mean that the natives of Sabah and Sarawak were left out in the cold as well.

The only senior DAP member who immediately reacted to the congress was P Ramasamy, deputy chief minister of Penang, who accused Zainal of race-baiting. The top leadership of DAP has kept completely silent on this issue, suggesting that they know any statements by them will lead to more racist taunts from right-wing Malay groups.

However, this silence reinforces the perception that DAP is now acting just like the MCA used to do during the previous regime of the BN coalition led by Umno. The MCA was routinely accused of being a "running dog" for not standing up to Umno’s racist utterances against non-Malays.

One could make the argument that Mahathir had to attend the congress in order to show the Malay polity that he was protecting Malay interests and to under-cut the PAS/Umno narrative that the Malays are being marginalised under the current Harapan administration. In fact, many people in Kuala Lumpur are saying that the "silent" organiser of the congress is actually Mahathir’s own party, Bersatu. Consequently, the real purpose of the event was to under-cut the pact between PAS and Umno.

Others argue that the congress was part of a larger plan to reset the Harapan administration. According to this line of reasoning, the purpose of the congress was to keep the pressure on Harapan to retain Mahathir as the leader and prevent a leadership transition to Anwar.

The end game is to keep the post of prime minister in the hands of the Bersatu while marginalising PKR and DAP. "Malay pressure" will also prevent DAP from advancing its political agenda while splitting PKR. Bersatu will then take in defectors from all parties and by the time of the next election, Bersatu will dominate Harapan just as Umno once dominated BN. In other words, Mahathir will have come a full circle.

The school of realpolitik says that Harapan must win a second term in 2023 to carry out real reforms. Real reforms will not be possible if Harapan loses in the next general election. It is the Malay polity who will decide who will be the winner in 2023, and the scare tactic employed by PAS/Umno is gaining traction in the heavily Malay-populated rural areas. If Mahathir, Bersatu, PKR and Amanah (the fourth component party of the Harapan) do not use the racial rhetoric, they will lose the Malay ground overnight.

The counter-argument is simple. Once you let the genie of hate speech and race-baiting out of the bottle, it is not possible to put it back in. There are a lot of impressionable young Malays in the community who have become indoctrinated by the racist ideology. The congress has not only reinforced these beliefs but, far more dangerously, it has co-opted Malay leaders from across the spectrum into telling the racists that their beliefs are vindicated. This slippery slope leads to one destination only: that of Malay fascism.

That is the ultimate Malaysian tragedy.

To extremists, all roads lead to DAP

JAMES CHIN is director, Asia Institute, University of Tasmania. The above first appeared in the Asia Dialogue.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.