COMMENT The ongoing Selangor crisis has riveted the Malaysian public for weeks and called into question the ability of the opposition to govern as a coalition.

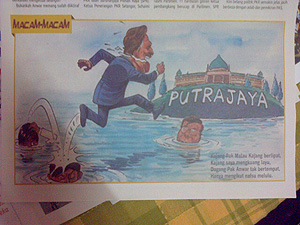

From attacks on each other to sackings and perceived party betrayals, the Selangor crisis has revealed underlying tensions among Pakatan Rakyat partners and showcased the fierce competition for power and positions within the national opposition itself.

This dynamics has overshadowed principles and escalated in tit-for-tat moves that reflect a family caught in battle. Emotions of anger and motivations of revenge have come to the fore, blinding many participants to the substantial deterioration of support among the public at large and to the shared struggles to strengthen Malaysia.

Most analyses to date have focused on the power contests among personalities and discussions of the steps taken in the crisis itself and their legal status. A number of commentators have highlighted the cost to public support and negative impact on governance.

This piece centres on developments within Pakatan. The argument developed below is that responsibility for the Selangor crisis must be shared across parties and leaders, and new approaches within Pakatan itself are needed to win back public trust and forge the common ground within the national opposition coalition.

Rise of undemocratic practices

When the crisis began is a matter of debate. Some point to when Azmin Ali’s supporters demanded their leader be given the post of Selangor menteri besar (chief minister) immediately after GE13 and openly revealed a lack of confidence in Khalid’s leadership.

Others point to the folly of the March 2014 ‘Kajang Move’, where the people were subjected to a by-election that revealed the inability of PKR to solve party problems in-house.

Others point to the folly of the March 2014 ‘Kajang Move’, where the people were subjected to a by-election that revealed the inability of PKR to solve party problems in-house.

Another focus was on mismanagement of governance challenges involving harmony among people of different religions and the state water crisis on the part of Abdul Khalid Ibrahim’s government.

The exact timing is moot, but a pattern has been clear: undemocratic pressures within Pakatan have been on the rise.

The most blatant example of this is the steps taken by Khalid in the past week, including the sacking of Pakatan executive council members (exco members) who opposed him.

In this action, Khalid has rejected the Pakatan coalition from which was elected to office, mistakenly believing that the vote in the last two elections were about him rather than the issues of better governance and inclusion that got him elected in the first place.

This is a common political mistake, where ego apparently fuels the misperception that the office is about the person holding the position, rather the people who put the leader in office.

The decision to go ahead and try to govern when it is clear, even without a formal vote of confidence, that he has a minority of support from the state legislature speaks volumes about Khalid’s prioritisation of self-interest over democracy and good governance.

It is indeed unfortunate that this path has been taken, for Khalid has made important contributions that should be recognised and appreciated. He still has valuable contributions to make, although given the reality of the current state of affairs, ideally in a new role.

Khalid is not alone in opting for undemocratic practices. A similar trajectory has been going on within PAS, where the conservative ulama-led faction has announced party decisions by decree, rather than through consultation and consensus reached by the elected executive political committee.

This has evolved after the PAS muktamar last year, when the ulama lost badly. They refuse to accept that the delegates voted decisively to stay in Pakatan and called for the leadership to reach more accommodative positions to strengthen PAS.

The decision over the move to tabling the hudud bill in Parliament last April, and more recently, pledging to support Khalid, were taken without adequately consulting the elected leaders in the party as a whole.

The conservative faction in PAS knows that it does not have the votes among the elected party leadership and refuses to recognise that PAS delegates did not elect many of them into leadership positions.

They are clearly uncomfortable with accepting difference and diversity. They would rather adopt undemocratic practices to impose their divisive agenda, rather than respect voters at large who supported Pakatan or even their own party delegates.

The conservative ulama group – many of whom are not actually ulama at all – also believe they have a special position that entitles them to putting their interests and opinions first.

Politics of confrontation

The misplaced political entitlement is only part of the current dynamics. For the past few months the opposition has applied opposition-like tactics against itself. The mode has been confrontation, rather than cooperation or even consultation.

The level of acrimony in the attacks make Utusan Malaysia and Umno barbs look tame. This is particularly true in PAS, where the young conservative ulama have forgotten the PAS culture of the years of Fadzil Noor ( right ) and engaged in all-out war.

PKR has followed suit, with DAP members also engaging in personal attacks. Only as fellow members in a family can, the attacks have gone after weaknesses and in anger, aimed to cause pain.

This focus on the negative has taken a life of its own, with attacks leading to counter-attacks and so forth. These have been ongoing for months tied to party contests for position. Pakatan has somehow forgotten that it opposes Umno, as it has concentrated energies inwardly and destructively.

It is clear that trust has eroded among Pakatan partners, and more polarised positions of laying blame and giving ultimatums have come to the fore. Words like ‘reject’, or ‘last chance’, and time periods of ‘24-hours’ and ‘immediately’ have narrowed opportunities to reach any compromise.

Issues and responses have been framed as all-or-nothing options, with decisions painted as the be-end-all for Pakatan. Problem-solving has taken a confrontational mode as issues are ‘forced’ onto others to reach a consensus that often is not a consensus at all but rather a bitter pill swallowed with bile and distrust.

Little reflection has taken the place of collective responsibility for the ongoing crisis, with frustrations, betrayals and disappointments overshadowing alternatives and more in-depth searches for common positions. For these parties long in opposition, confrontation is the easy route, for it is a familiar scene.

This situation is exacerbated when every position and decision-maker believes that he or she is right. It is much more difficult to opt for compromise in this confrontational mode.

The sad reality is that confrontation politics has worsened the Selangor crisis. No one likes to be pressured, a sultan or otherwise. The current face-off appears to make the crisis follow the zero-sum path of Perak, rather than take a page from the lessons of Terengganu and Perlis.

In these crises, accommodation, mutual respect and compromise ruled. To use the strategy of forcing an issue to reach ‘consensus’ on the sultan, or any of the key players, is inherently vulnerable to breakdown.

Further, to take a crisis to the royalty or to the courts puts pressures on Malaysia’s political institutions and, more often than not, the result has undercut democracy, rather than strengthened it. It is foolhardy to think that weakened institutions can offer a fair hearing in the current political climate.

Need for exit strategies

What then are the options ahead in what appears to a political impasse? The challenge for Pakatan has always been the ability to accommodate minority views, and reach compromises.

This is what distinguishes Pakatan from Umno, the level of compromise needed to maintain inclusiveness. This has been difficult from the start, and the Selangor crisis showcases this further.

This crisis is primarily about personalities and, as such, there is room to manoeuvre and reach some sort of genuine consensus. If the current slate of candidates is not working, then Pakatan leaders need to go back to the drawing board on the candidate slate for the current leadership.

A crucial element in this regard is to tone the rhetoric and to refrain from taking positions that escalate conflict, rather than open the way for compromise. There needs to be a return to common ground, rather than points of division. This will be a test of Pakatan’s leadership.

If they fail, the voters will punish them. Ordinary Malaysians will not elect a coalition that cannot work together, least of all govern together.

Along with changing the approach to the crisis, a crucial dimension is to provide viable face-saving exit strategies for key players. One of the lessons, of similar crises in Umno, is the ability to find alternatives roles for different actors, to dampen acrimony and move forward.

While the opposition does not have the financial incentives of the BN, viewing the Selangor crisis narrowly has limited possible avenues.

A more challenging element in the long-term viability of any solution involves a regeneration of leadership within both the parties most affected by the crisis – PKR and PAS.

Along with Khalid, Abdul Hadi Awang and Anwar Ibrahim could consider new roles in the opposition. The differences among top leaders will constrain the opposition to regenerate and resolve its differences.

Within PAS, Hadi ( right ) is seen to have mismanaged GE13, with his decisions contributing to the loss of three states for PAS - Kedah, Terengganu and Perak. His ailing health has prevented him from bridging the differences within his own party. In fact, many of his decisions have worsened divisions within PAS, for Hadi is believed to have moved from being a bridge-builder to represent the conservative flank.

For PKR, the challenge is to move beyond being a personality-based party and to develop a core of younger, capable leaders with governing experience. The longer the Selangor crisis continues, the more younger members in the party are becoming embroiled in it.

Rather than being a unifying figure, as he has been in the past, Anwar has become, for some in Pakatan, a focal point for division. Pakatan’s future will depend on these leaders taking on new roles or returning to more bridge-building positions.

Crises at the state level are common in Malaysian politics, and will continue to occur. Umno has survived many of these and so will Pakatan.

But the form Pakatan will take, and the standing it will have, will depend heavily on whether the players and parties stop fighting and remember the reasons they became one family, for which the number one reason was to serve Malaysians, not themselves.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Center for East Asia Democratic Studies of National Taiwan University and can be reached at [email protected]